Ace · Globestyle CDORBD 066

1989

Ace · Globestyle CDORBD 066

1989

01 - Mtindo wa Mombasa [5:08]

“this is the way do things in Mombasa”

Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm kumbwaya · Maqam bayati

02 - Maneno tisiya [6:25]

“nine reasons”

Mohamed Kijuma, Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm twari · Maqam saba

03 - Wanawake wa Kiamu [12:01]

“the ladies of Lamu”

Mohamed Kijuma, Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm kumbwaya · Maqam saba

04 - Taksim bayati [4:28]

Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Maqam bayati

05 - Baina macho na moyo [6:27]

“between the eyes and the heart”

Khuleita Said Muhashamy, Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm samba · Maqam shuri

06 - Mwiba wa kujitoma [5:04]

“a thorn in the flesh”

Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm goma · Maqam hijazi

07 - Binti Mombasa [6:02]

“the daughter of Mombasa”

Ali Said Mashjury, Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm wahed-u-nus · Maqam bayati

08 - Nataka rafiki [5:28]

“I want a friend”

Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm chacha · Maqam hijazi

09 - Mwana hasahau mama [5:31]

“a child does not forget its mother”

Khuleita Said Muhashamy, Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Rhythm kumbwaya · Maqam rast

10 - Taksim jirka [5:34]

Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody

Maqam jirka

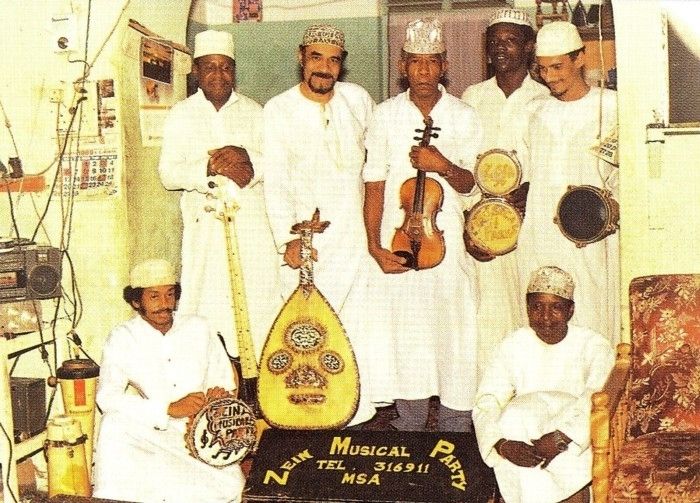

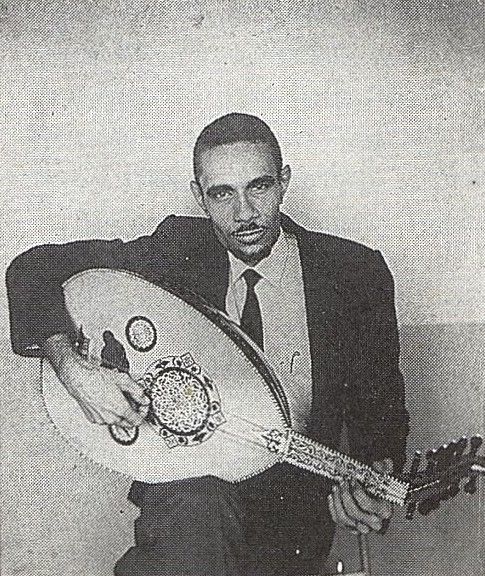

Zein L’Abdin Ahmed Almoody, ’ud & vocals

Mohamed Ahemd Bwanchuoni, violin

Bakari Salim, keyboard & dumbak

Juma Bakari Chera, bass guitar & bongos

Mohamed Hafidhi, dumbak, bongos & chorus

Omar Abdurasul, bongos & chorus

Mbarak Absillahi, rika (tambourine) & chorus

recorded in Mombasa, Kenya, februrary 1989

The lyrics of ‘Mtindo Wa Mombasa’ seem to be caught between

two lines of argument: one stresses the theme of community and

reciprocity, the other refers to the commercialisation of social

relations in today's Mombasa and the world in general. The two are also

a likely portrayal of the contemporary working conditions of taarab

musicians in Mombasa, being caught between the demands of community

still intact in many ways and the requirements of a commercial music

scene.

These features are also aptly mirrored in Zein's character and

lifestyle: Zein is a family man and his place in the Old Town of

Mombasa is always open to everyone from the community who wishes to pop

in. On the other hand Zein is strictly professional. While he tries to

keep away from the hustle and bustle of Mombasa's taarab scene and the

shrewd business acumen of some, he is a strict entrepreneur. For more

than ten years he has refused to record for others and has only

produced cassettes on his own, which he distributes from his living

room. Engagements are strictly cash, a fact criticised by the wazee,

Mombasa's honourables, who are sorry he does not like to just come out

and entertain them at their sit-togethers.

Zein might be an iconoclast — he never goes out except when he

has to play — but once he gets up in the early afternoon, his

place at ground level on Ndia Kuu Road, is open to a steady stream of

visitors, be they friends, relatives or the occasional customer wishing

to buy a cassette or arrange for him to play a taarab at their wedding.

Hot Arabic coffee or cold water for refreshment welcomes every visitor.

Zein's evenings are usually spent with friends and fellow musicians,

chewing miraa (a mildly narcotic twig), listening to and discussing

music — with him making a point here or there on the ’ud

— or watching videos. Once the scene gets quieter around midnight

he might get down to some more serious work, honing a new lyric until

it fits the formal demands of Swahili poetry and sounds good sung, or

working on a new song until the early hours of the morning.

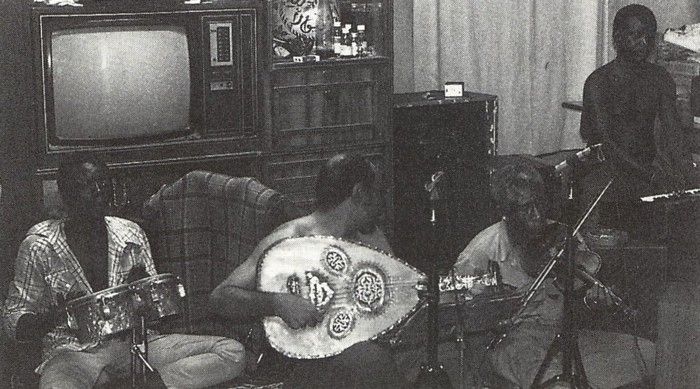

It may seem a perfectly natural idea to record Zein and band in this

familiar environment, but it had its problems. After a first plan to

record in a local studio proved futile we decided to set up in Zein's

living room. We had to wait until close to midnight when the stream of

visitors lessened, and the street noise quietened. The door and windows

were shut and the recording space was additionally fenced off by

blankets spread across the room. We still had to cope with a few cars

and motorcycles passing at arm's length from the front door, and with

the video from upstairs. The ventilators and the fridge had to be

switched off during recording because of the hum they produced.

February is in the middle of the hot season in Mombasa and you may

imagine the amount of sweat produced during the two nights of

recording. If the sultry weather shows in these recordings at all,

good! Not all the conditions were adverse, and we should not forget to

mention the general hospitality of Zein and his wife, the delicious

foods, spiced tea and the ever-present cups of hot coffee. Shukrani

nyingi sana! If you can hear background sounds — street

noise, coughing, coffee cups rattling — this is perfectly

natural. What you hear is what we heard — the sound and style of

Mombasa.

ZEIN L’ABDIN AHMED ALAMOODY was born in Lamu on May 30,

1939. In his family, music and the other arts were highly esteemed. His

father played the ’ud as a pastime. Zein remembers a kibangala,

one of the old stringed Swahili lutes, hanging from the wall though he

never saw his father play it. Guests were often entertained with

musicians, and Baskuta was a regular visitor. Zein did not begin to

play the ’ud until after his father died in 1951 when he came to

Mombasa to live with an uncle. He attended school there up to 1954 but

had to stop because of some misunderstandings within the family. After

time back in Lamu he went to work as a hotel clerk in Mombasa. Around

this time he also picked up the ’ud. Zein was never formally

taught by anyone but learned by seeing, listening to and asking other

’ud players questions. He often went to the home of the tailor,

Omar Awadh Ban, a well known ’ud player of the time (who recorded

for the Jambo label in the late 40s), and stayed whole nights playing

and discussing music.

In 1957/58 Zein joined the ’ud player Ali wa Lela as a second

singer (wa Lela had worked at Zein's father's house in the 40s and had

picked up ’ud playing there). They recorded occasionally for

Sauti ya Mvita, the radio station at Mombasa. Wa Lela then went to the

Gulf states by invitation, but died there soon after. Zein finally

managed to get his own ’ud in around 1958, made by a local

craftsman. Three years later he got an instrument made in Arabia. At

that time he also left his work in the hotel and became a professional.

After a first recording for the Arrow label in the early 60s Zein

joined Mzuri Records, then Mombasa's main taarab outlet. He recorded a

host of singles up to the mid-70s, occasionally featuring other singers

with his band, at weddings and on records. Zuhura sang with his group

for a while and also Maulidi Juma. In the second half of the 70s Zein

recorded for Mbwana, a thriving cassette store in Mombasa's old town.

While earlier he had to rent his instruments and amplification from

that store he has since gone out on his own. Though the line-up is

smaller (he can no longer afford a bass player), the changes have done

him good. Zein plays regularly at weddings and distributes his own

cassettes (more than 50 titles in both Swahili and Arabic) from his

flat in Mombasa's Ndia Kuu Road. Once or twice a month he plays in one

of the tourist hotels on Mombasa's south coast. He does not consider

this a sell-out, and it is a regular sort of income. It also gives him

some independence from the wedding circuit, so he can pursue his own

musical direction.

THE MUSIC

Zein's group of the 70s featured the accordion, violin and bass in

addition to the obligatory percussion and his own ’ud. The

standard line-up for the past ten years has been: ’ud, violin,

keyboard, dumbak, bongos and rika (tambourine). On some tunes on this

CD, Juma Bakari, Zein's bass player through the 70s, was added to the

regular line-up.

While he went along with the demands of the Mombasa scene in the 60s

and early 70s, playing Indian-style taarab and including singers like

Zuhura and Maulidi, Zein has since abandoned going for the latest

trends, honing his own style rooted in the Lamu traditions: “For

some time I too have sung with an Indian tone like the others. But I

realised it is of no use. I have my own culture, I live my traditions,

it is awkward for a musician like me to follow foreign music. It does

not sound good.” Zein is no purist though. He keeps his

“reference collection” as he calls it, of music cassettes

from all over the world and likes Rai just as well as the Egyptian

star, Farid Al-Atrash or Salsa. That he knows the history of his

instrument and the links to Spanish traditions is shown when he

ventures from a classical taksim (an ’ud solo improvisation) via

some hot flamenco strumming into ‘Malagueña’.

Zein is one of the few contemporary taarab musicians who is well-versed

in the music's traditions. This includes his knowledge of Arabic music

theory — acquired from taping BBC Arabic music broadcasts which

featured ’ud virtuosos Jamil and Mounir Bashir and explained the

various maqamat (modes) — as well as the Swahili

traditions of ngoma rhythms and dances and the Swahili poetry

of old. Besides his repertoire of Swahili songs and his Swahili

cassettes, Zein also sings and records in Arabic. He is often invited

to play at the ‘Arabic weddings’ in Mombasa or to play for

visitors. His cassettes and ’ud playing are known and respected

as far as Yemen, the Gulf and Egypt.

There is no Swahili system of modes like the maqamat. The maqam

that comes closest to Swahili melodic traditions is saba. It is

no coincidence that this is the maqam used on the two oldest songs in

this collection ‘Maneno Tisiya’ and ‘Wanawake Wa

Kiamu’. Other maqamat featured here include bayati

(‘Mtindo Wa Mombasa’, ‘Taksim Bayati’, an

instrumental solo in maqam bayati, ‘Binti Mombasa’), shuri

(‘Baina Macho Na Moyo’), hijazi (‘Mwiba Wa

Kujitoma’, ‘Nataka Rafiki’), rast

(‘Mwana Hasahau Mama’) and jirka (‘Taksim

Jirka’).

The distinctive Swahili touch comes in terms of ‘voice’

qualities and especially in the rhythms and the dances and occasions

associated with them. In general these are derived from Swahili ngoma

— male and female dances, originally accompanied by the nzumari,

a type of oboe, ngoma (drums), or yugo (cow-horns beaten with a stick)

and various other percussion instruments.

The twari rhythm of ‘Maneno Tisiya’ derives from twari

la ndia, a street procession/dance originally performed at weddings

of better-class families. The goma is a dance that was performed by the

older, respected male members of society at religious festivities like

the Maulidi (birth of the Prophet Mohamed) or at weddings. The goma

rhythm backs up the song ‘Mwiba Wa Kujitoma’. Definitely

the most popular taarab rhythm along the coast is kumbwaya. The

kumbwaya is a kind of drum and also a dance that was danced for

amusement or to treat psychological disorders. The songs ‘Mtindo

Wa Mombasa’, ‘Wanawake Wa Kiamu’, ‘Mwana

Hasa-hau Mama’ use this rhythm. The wahed-u-nus of

‘Binti Mombasa’ is a rhythm from the Arabic peninsula and

simply means ‘one and a half’. The samba and chacha of

‘Baina Macho Na Moyo’ and ‘Nataka Rfiki’

respectively are self-explanatory.

The Zein Musical Party plays a style that the Swahili variously call

‘men's taarab’ or taarab ya Kiarabu. The taarab of the

likes of Maulidi, Zuhura or Matano in Mombasa or the various styles of

the Tanzanian coast from Tanga to Zanzibar are played at women's

wedding celebrations, hence ‘women's taarab’. (Check

“Mombasa Wedding Special” by the Maulidi Musical Party,

Globe. Style CD/ORBD 058 for a description of women's wedding

celebrations and taarab performed at these weddings). The latter kind

of taarab is also often referred to as taarab ya Kiswahili, or, because

of the Indian leanings of much of Mombasa's taarab, taarab ya Kihindi.

The Zein Musical Party plays at men's wedding celebrations, where the

main public are males, while the celebrations of the women are fenced

off with a curtain, according to Islamic customs. A special feature of

this kind of taarab are the dances performed by the wedding guests and

bridegroom. Some of the dances are from the Arabic peninsula and are

referred to by their geographical origin, like Sanaani (from Yemen) or

Kuwaiti. Seyyid Ah Baskuta, who witnessed the introduction of some of

these dances to the Lamu area in the early thirties, points out how the

dances introduced by sailors from Kuwait fitted incredibly well with

ngoma rhythms from Lamu and suggested an earlier link between these two

traditions. In fact African musical traditions have made many inroads

into the music of the Arabic peninsula and around the Gulf. Various

East African musical instruments and complete musical genres of African

origin are still performed today in Kuwait and southern Iraq.

LAMU AND SWAHILI

POETIC TRADITIONS

For centuries Lamu had been the acknowledged centre of Swahili culture,

famous for all aspects of the arts and especially for its poetry. The

expansion of the Omani court in Zanzibar throughout the second part of

the 19th century and the colonial onslaught from the turn of this

century onwards, and its concentration on the Mombasa-Nairobi axis, led

to the decline of Lamu as a port and trade centre. Zein in his youth

may have witnessed the last days of this past glory, when Lamu was a

major patron of the arts. There was an exodus of men to Mombasa and

other towns closer to the new centres of power after World War II. This

included Seyyid Ali Baskuta, the first ’ud player in Lamu, and a

walking thesaurus of Swahili musical traditions, and also the young

Zein. No professional taarab group operates in Lamu today.

Zein remembers his roots though: he speaks of his uncle Baskuta as

“the one who had the greatest impact on me in terms of his

knowledge and capabilities. He was always around while we grew up, he

played at our house when we had guests.” Another important

intermediary, a fellow Lamuan and one of Zein's neighbours in Mombasa,

is the well-known poet Sheikh Ahmed Nabhany. Nabhany owes his

reputation not only to the quality of his poetry, but also by

researching into and preserving the cultural traditions of Lamu and the

Northern Kenya coast. He introduced the ’ud player to the lyrics

of many of the old Lamu songs in his repertoire, ‘Maneno

Tisiya’ and ‘Wanawake Wa Kiamu’ among them. Zein also

sings a number of Nabhany's poems.

Both Baskuta and Nabhany name Mohamed Kijuma as one of the leading

poets and performers in Lamu around the turn of the century. Back then

the music was not called taarab, but the existing descriptions of the gungu

poetic contest/dance and the kinanda dance show a clear

similarity in character. Kijuma excelled not only as a singer and

player of the kinanda — or kibangala as it is called in Lamu (a

seven-stringed lute of the Swahili coast, related to the family of the gambus).

He was also a proficient dancer at the ngoma. After witnessing one of

his performances in Lamu, the Sultan of Zanzibar invited Kijuma to the

island to lead and train an orchestra and dancers. A photograph taken

in Zanzibar in 1907 shows Kijuma playing the kibangala. Popular memory

attributes the lyrics of both ‘Maneno Tisiya’ and

‘Wanawake Wa Kiamu’ to Kijuma's pen. ‘Maneno’

is an old wedding song which Kijuma may simply have preserved in

committing it to paper. ‘Wanawake’ honouring/describing the

beauty and character of the ladies of Lamu is close to another

masterpiece of Swahili poetry, the ‘Ode to the Lady of

Manga’ attributed to the mythic hero Liongo.

Zein's songbook contains more than 400 entries, the majority of which

are his own poetry. It is also common for well-known poets to give some

of their best poems to specific singers or musical parties to sing.

While these poems are committed to paper in the first place and have to

agree to well defined standards of rhyme, they are invariably meant to

be sung.

Werner Graebner