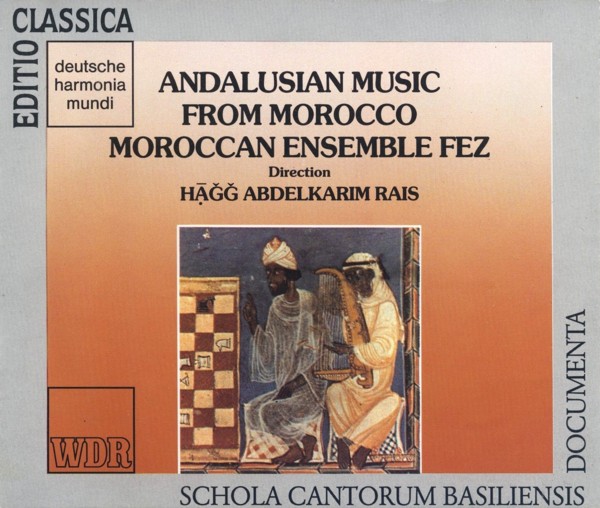

Andalusische Musik aus Marokko · Andalusian Music from Morocco

Marokkanisches Ensemble aus Fez · Moroccan Ensemble Fez | Abdelkarim Rais

medieval.org

Schola Cantorum Basiliensis Documenta

LP, 1984:

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (EMI) 1C 16 9525 3 / 1C 2LP 153

CD, 1991:

Deutsche Harmonia Mundi (BMG) “Editio Classica ” GD 77 241

[recorded 1977]

Um den zyklischen Charakter dieser Musik zu wahren,

wurde keine detaillierte Einteilung in einzelne Tracks vorgenommen

In order to preserve the cyclical character of this music,

the recording has not been divided into individual tracks

CD 1

[48.48]

naubatu r-raSdi, mīzānu l-quddāmi

(1.Teil/first part)

al-bugyatu (rhythmisch nicht gebundenes Instrumentalvorspiel)

at-tawshiyatu (rhythmisch gebundenes Instrumentalvorspiel)

aS-San‘atu 1 - al-laylu laylun ‘ajībun („Die Nacht ist eine wunderbare Nacht“) B:93/1 M:166/1

aS-San‘atu 2 - anā qad ‘ayya Sabrī („Meine Standhaftigkeit ist schwach“) B:93/2 M:167/n2

aS-San‘atu 3 - qalbī tarahū yafrahu („Die siehst est, mein Herz ist frölich“) M:167/3

aS-San‘atu 4 - yāTal‘ata al-badri („Oh Schönheit des Vollmondes“) M:167/4

al-baytāni

(Gesangsimprovisation)

aS-San‘atu 5 - katamtu l-maHabbata sinīna („Jahrelang habe ich die Zuneigung verschwiegen“) M:170/15

aS-San‘atu 6 - nahwā mina l-gizlāni („Unter der Gazellen“) B:93/3 M:169/10

aS-San‘atu 7 - al-lā'imu lā yulawwimunī („Der Tadler tadelt mich nicht heftig“) M:390/13

naubatu r-raSdi, mīzānu l-quddāmi

(2.Teil/second part)

aS-San‘atu 8 - awHashat mudh gibta („Es ist einsam du weg bist“) M:176/29

aS-San‘atu 9 - ayyuhā as-sā'ilu („Oh Bittsteller“) M:176/30

aS-San‘atu 10 - ammā qad Hafita („Du warst verborgen“) M:101/2

aS-San‘atu 11 - yā muqābilu („Oh Gegenüber“) B:94/5 M:177/34

aS-San‘atu 12 - yā man malakani ‘abdan („Oh wer mich Diener beherrscht“) B:94/6 M:177/35

al-mawwālu

(rhythmisch nicht gebundene Gesangs- und Instrumentalimprovisation)

aS-San‘atu 13 - tayyahtanī bayna l-anāmi („Du bringst mich in Verwirrung“) B:95/7 M:179/2

aS-San‘atu 14 - qum tarā r-rauDa („Steh auf, betrachte den Garten“) M:178/37

aS-San‘atu 15 - ayyu Zabyin ‘alā l-asadi („Welche Gazelle kämpft mit dem Löwen“) M:215/37

CD 2

[54.25]

naubatu l-māyati, mīzānu l-basīT

al-bugyatu (rhythmisch nicht gebundenes Instrumentalvorspiel)

at-tawshiyatu (rhythmisch gebundenes Instrumentalvorspiel)

aS-San‘atu 1. unZur ‘ilā raunaqi l-‘ashīyati („Sieh den Glanz des Abendhimmels an“) B:37/1 M:352/1

aS-San‘atu 2. al-‘ashīyatu aqbalat bi-l-iSfirāri („Der Abendhimmel wird gelb gefärbt“) B:37/2 M:352/2

al-baytāni

(Gesangsimprovisation)

aS-San‘atu 3. al-‘ashīyatu fi l-iSfirāri („Der Abendhimmel in Gelbfärbung“) B:38/4 M:354/6

aS-San‘atu 4. qum ‘āyini l-‘ashīyata („Steh auf, schau dir den Abendhimmel an“) B:38/5 M:357/7

aS-San‘atu 5. yā ‘ashīyatu („Oh Abendhimmel“) B:39/6 M:355/12

aS-San‘atu 6. unZurú Samsa l-‘ashīyati („Seht die Sonne des Abendhimmels an“) B:39/7 M:355/12

aS-San‘atu 7. qum tarā Samsa l-‘ashīyati („Steh auf, betrachte die Sonne des Abendhimmels“) B:40/8 M:356/13

aS-San‘atu 8. qad ashraqad shamsu l-gabini („Schon scheint die Sonne der Stirne“) B:40/9 M:277/19

naubatu l-māyati, mīzānu l-quddāmi

al-bugyatu (rhythmisch nicht gebundenes Instrumentalvorspiel)

at-tawshiyatu (rhythmisch gebundenes Instrumentalvorspiel)

aS-San‘atu 1. al-‘ashīyatu ilā l-gurūbi („Der Abendhimmel verdunkelt sich“) B:50/1 M:367/1

aS-San‘atu 2. wa-‘ashīyatin („Beim Abendhimmel“) B:50/2 M:367/2

aS-San‘atu 3. jā'a a l-habību („Der Freund ist gekommen“) B:50/3 M:370/12

aS-San‘atu 4. yā sāhibā („Oh Gefährte“) B:51/4 M:369/8

al-mawwālu

(rhythmisch nicht gebundene Gesangs- und Instrumentalimprovisation)

aS-San‘atu 5. a‘Zam yā ‘ashīyatu („Séi erhaben, oh Abendhimmel“) B:51/5 M:369/8

aS-San‘atu 6. shamsu l-‘ashīyi qad garabat („Schon geht die Abendsonne unter“) M:375/30

aS-San‘atu 7. anā kullīyun milkun lakum („Ich bin euch völlig ergeben“ mit interpolierter tawshiyatun) B:51/6

aS-San‘atu 8. samsu l-‘ashīyati raunaqat („Glanzvoll ist die Sonne des Abendhimmels“) B:51/7 M:378/40

Hajj ‘abdelkarim rais, rabab, Gesang/voice

muHammad bajdub, Gesang/voice

sidi samlali, Violin/e, Gesang/voice

muHammad ben hayyun, Violin/e, Gesang/voice

Hajj muHammad buzuba, ‘ūd, Gesang/voice

SaleH sherki, qānūn, Gesang/voice

Hajj muHammad tazi, Tār, Gesang/voice

Hajj ‘abdelahad ‘amri, darābukka, Gesang/voice

Leitung/Direction: HAJJ ‘ABDELKARIM RAIS

rabab :

zweisaitiges Streichinstrument | two-stringed bowed instrument

‘ūd :

Laute | lute

qānūn :

Zither mit trapezförmigem Resonanzkasten | zither with trapezoidal soundbox

tar :

Tambourin mit Schellen | tambourine with jingles

dardbukka :

einfellige Bechertrommel | single-headed goblet drum

[CD]

[CD]

Ⓟ 1984 harmonia mundi, D-7800 Freiburg

© 1991 Schola Cantorum Basiliensis

Aufnahme/Recording: Robert Lattmann

Aufgenommen/Recorded: 3. 2. 1977

Phonag Tonstudio, CH-8307 Lindau ZH

Kommentar/Liner notes: Thomas Binkley

Übersetzungen/Translations:

Meinrad Schweizer, Anne Smith, Genevieve Begou, Isabel Rodriguez-Nogueras

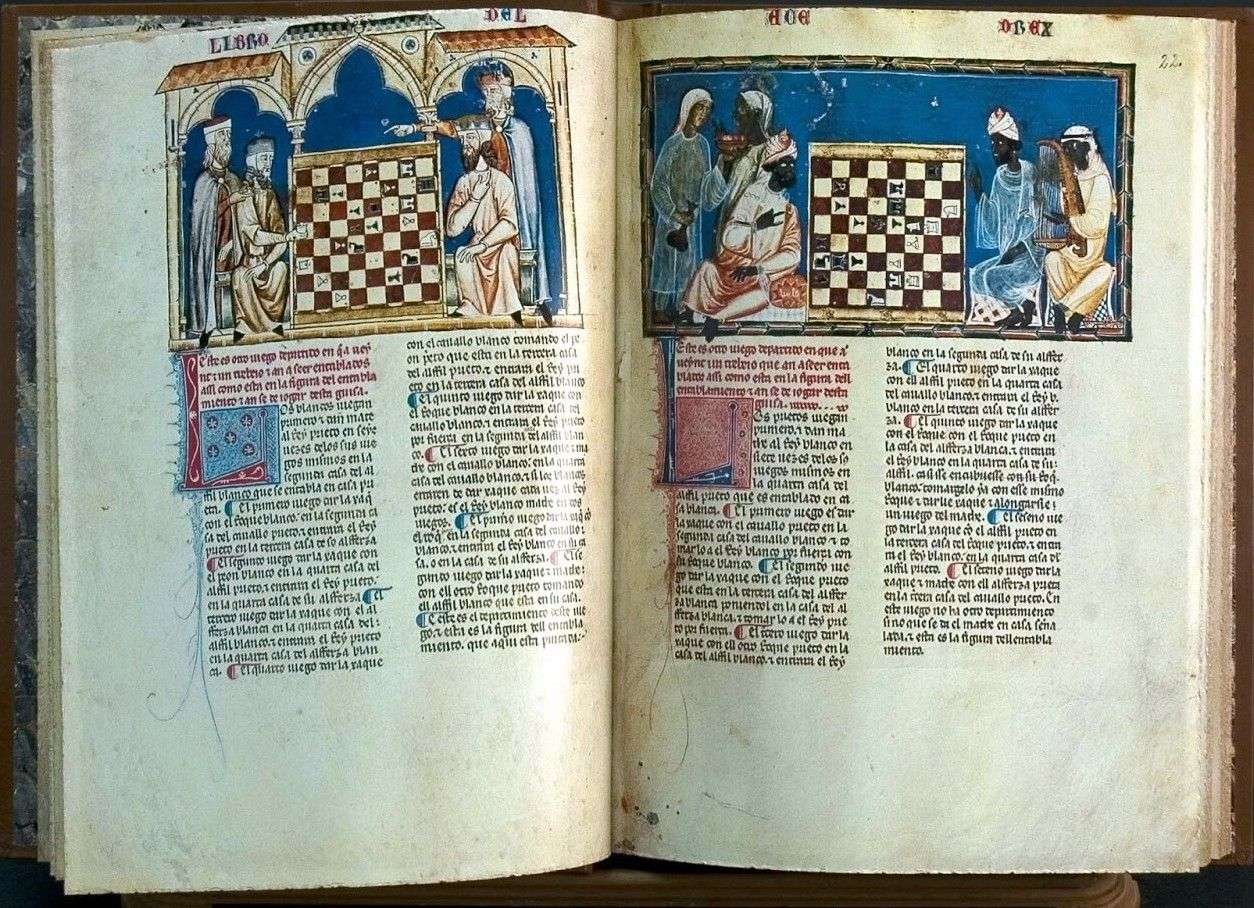

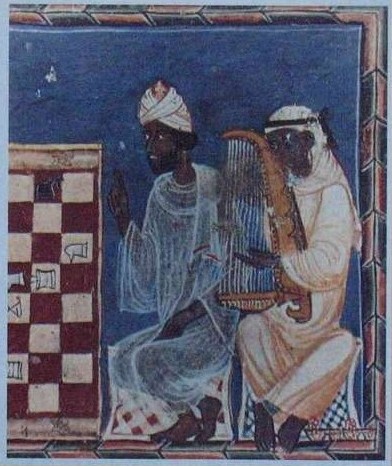

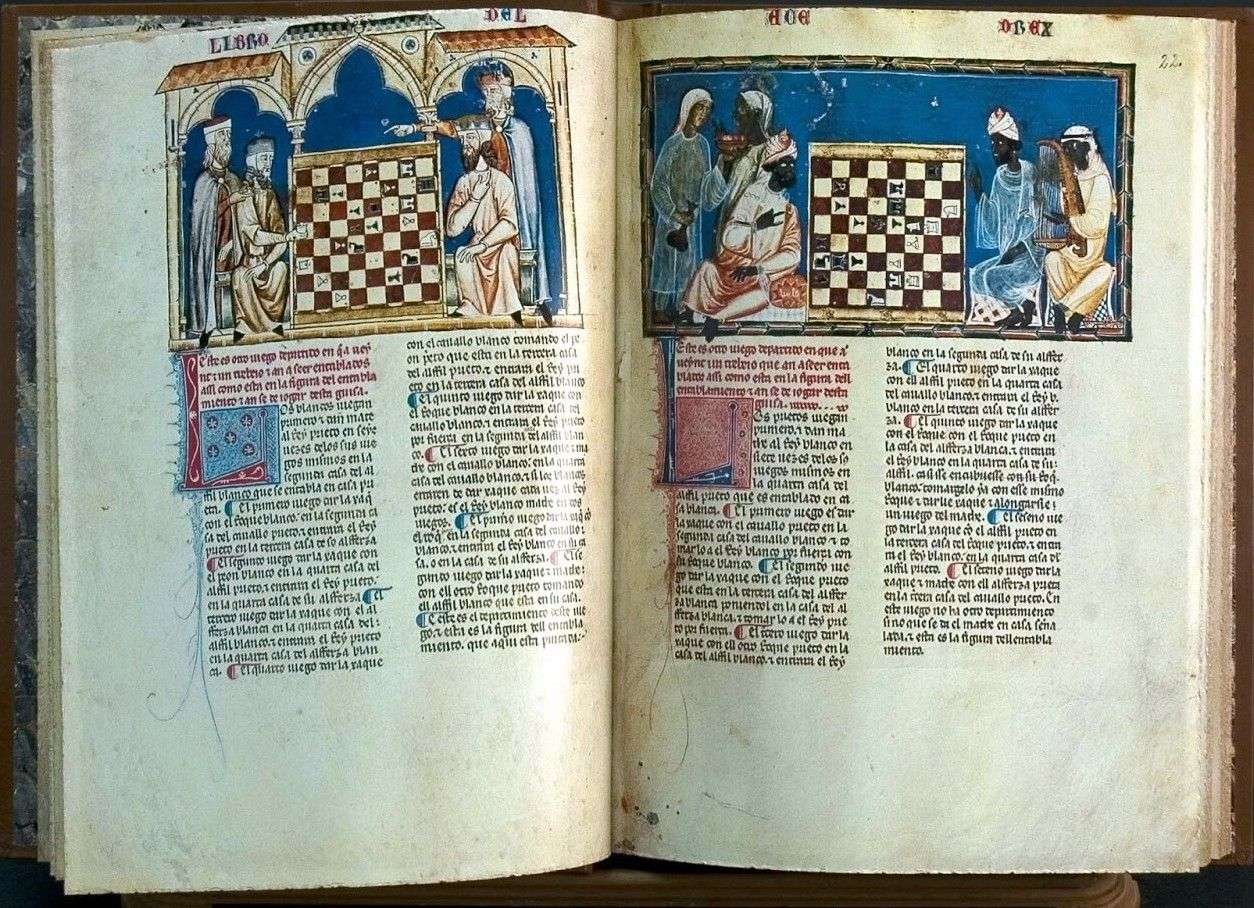

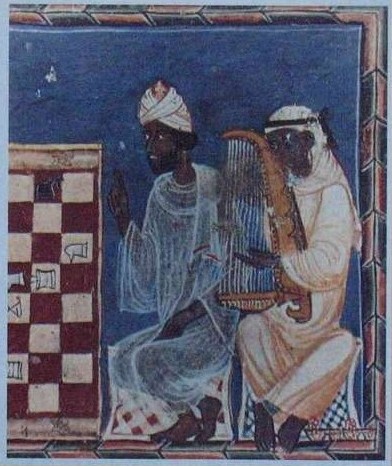

Titelbild/Front cover picture: Miniatur aus der Cantigas-Handschrift/

Miniature from the Cantigas manuscript

El Escorial, Real Monasterio de El Escorial, T.j.1.

Mit freundlicher Genehmigung des/by kind permission of the

Patrimonio Nacional, Tesoro Artístico, Madrid

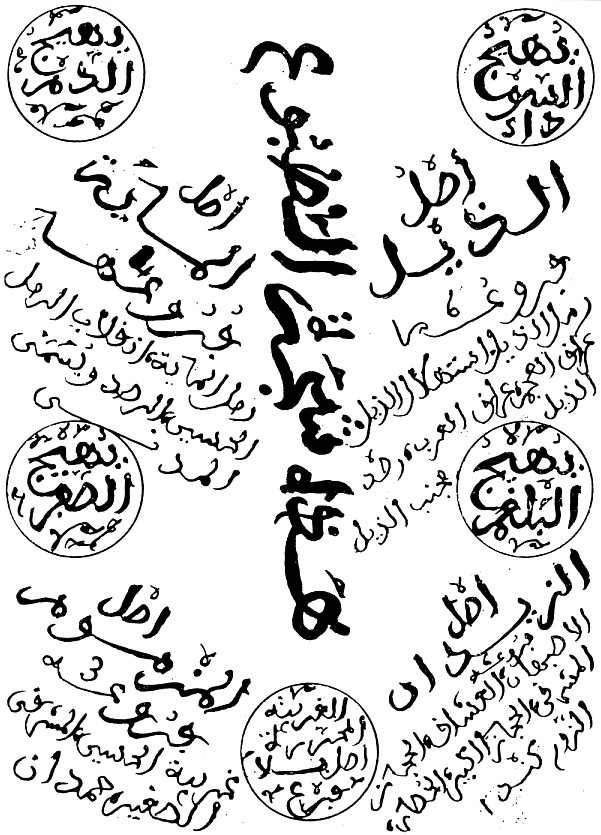

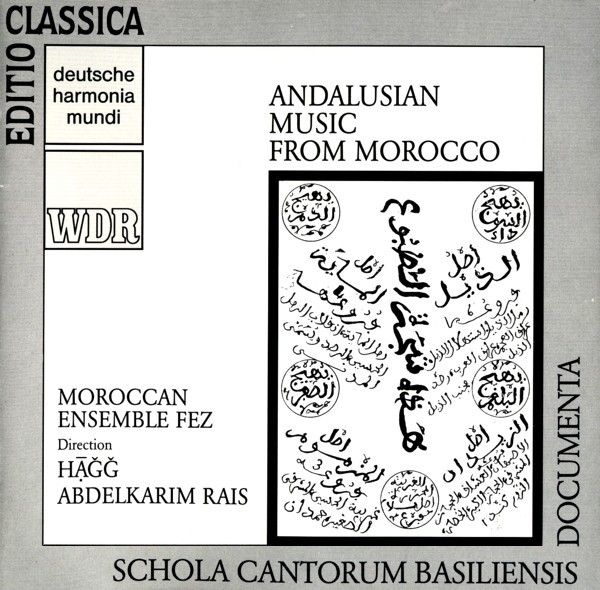

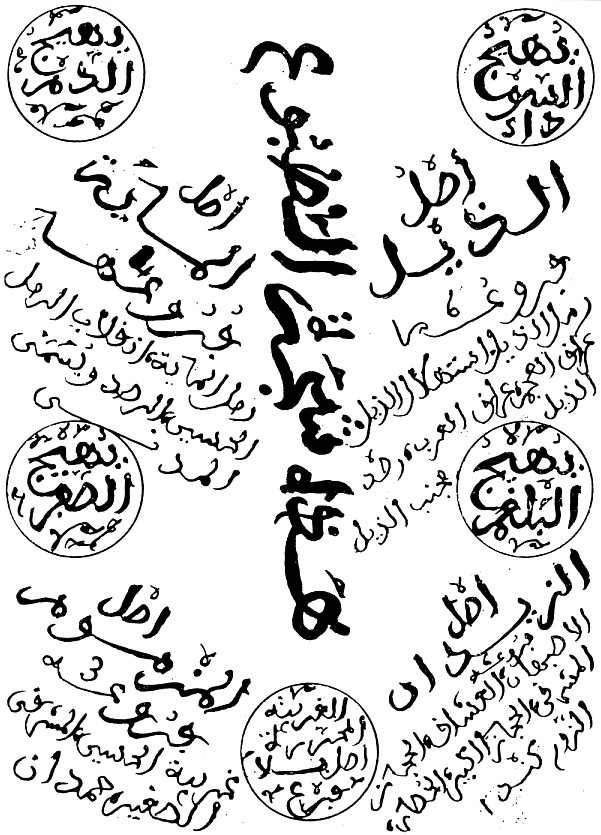

Titelbild/Front cover picture Booklet:

Die Tafel zeigt einen Baum mit „Stämmen“ und „Asten“,

der das System der in der „andalusischen“ Musik verwendeten 24

Tonarten darstellen soll. Die vertikal angeordnete Schrift in der Mitte

(hadha shajaratu T-Tubū‘i:

„Das ist der Baum der Tonarten“) bildet den Grundstamm, um den

links und rechts vier „Stamme“ mit ihren „Ästen“

angeordnet sind; der fünfte „Stamm“ (unten in der Mitte) hat

keine „Aste“.

Das Bild ist eines der wenigen Zeugnisse mit

theoretischem Ansatz zur nordafrikanischen Musiktheorie und wird

erstmals von dem Marokkaner muHammad al-Bū‘isāmī (+1690) erwähnt.

Booklet cover illustration: The table shows a tree with “limbs” and

“branches” representing the system of 24 tonalities employed in

“Andalusian” music. The vertically aligned inscription in the center (hadha shajaratu T-Tubū‘i:

“This is the tree of tonalities”) forms the trunk, to the left and

right of which are arranged four “limbs” with their “branches”. The

fifth “limb” (bottom center) has no “branches”.

This illustration is one of the few sources dealing with rudiments of North African

musical theory and was first mentioned by the Moroccan muHammad al-Bū‘isāmī (+1690).

Redaktion/Editing:

Thomas Drescher (SCB)

Dr. Jens Markowsky (dhm)

All rights reserved

HARMONIA MUNDI D-7800 FREIBURG

Eine Co-Produktion mit dem | A co-production with

Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln

Introduction

This recording cannot fail to stimulate

interest in the history of Western culture as it is preserved in

non-European traditions. Here we take up one fascinating musical

tradition of North Africa, a descendant of medieval Hispano-Arabic music

which migrated to the Moslem Mediterranean world as the Moors were

driven from Spain during the centuries of conflict, the reconquista,

completed by the Catholic kings at the close of the 15th century; a

music which in its pure state is unlike any other Moslem musical

tradition, one which since the 18th century has become stabilized in its

repertory and in its performance practice.

There is a very large

literature concerning the contributions of the Hispano-Arabs to

Christian civilization in languages, sciences and arts, a literature far

too complex and detailed to review here. One tributing is of importance

in charting the awakening of interest in the music of the Maghreb. The

painter Nicolas Jacques Conte (1775—1805) was appointed by Napoleon

Bonaparte to accompany a team of researchers forming an expedition to

Egypt. He was to capture Egypt in countless sketches and paintings of

subjects about which the other team members were to write. The results

of that expedition is contained in the 24 volumes of the remarkable Description de l'Egypte,

10 volumes of text, 14 oversized volumes of plates published in two

editions between 1809-28 and 1821-30. This is a rich source of

information on virtually every aspect of 18th century Egyptian life,

including music. Villoteau's “de l'etat actuel de l'art musical en

Egypte” includes explanations of Maqqam, Ethiopean notation,

improvisation on a single note, Coptic chant, Jewish music, musical

instruments and much more. Conte illustrated this discourse with a great

many plates.

This enormous study stimulated interest in the

music of the non-European Mediterranean world, and led to other works

such as Edward William Lane's mid 19th century An account of the Manners and Customs...

(still in print today) which also touches upon musical practices. Of

more importance for us is Salvador Daniel, who before he was executed

was for a few days the director of the Paris Conservatoire during the

commune of 1871, and who wrote La musique arabe: ses rapports avec la musique grecque et le chant grégorien,

Algiers 1863 / 2nd edition 1879, and later translated into English by

Henry George Farmer, an outspoken defender of the thesis of Arabic

influence on Western music. Daniel included the first — as far as I am

aware — piece of Andalusian music to appear in Western literature, a

piece he called “Heuss-ed-Doure, a Moorish song from Algiers”. Actually

it is a section from the Nouba meia [Núba al-Maya] contained on this

record (see Compact Disc 2).

In 1922 a musicological controversy arose with the publication of the Arabist Julian Ribera's La música de las Cantigas (Madrid 1922), followed by La música andaluza medieval en las canciones de trovadores...,

3 vols, 1923-25. Ribera sought the rhythmic solution of the notation of

the Cantigas de Santa Maria in Arabic practices, a standpoint shared

with few music historians. The suggestion of some connection between the

Hispano-Arabic music and the Cantigas has remained alive in spite of

the negative reception of Ribera's thesis. Indeed, interaction between

the Moslem, Jewish and Christian civilizations has been studied

extensively in literature. Nyhl and later Briffault along with many

others defended the Arabic thesis of influence of the Arabs on courtly

love and troubadour lyric. Others supported the opposing theses of

classical heritage, while a few wrote about a spontaneous development.

Le Gentil in a little book about the villancico tried to present the

conflicting theses in perspective. In 1953 Samuel Stern published his

remarkable discovery that the final verses of the Andalusian muwashshahs

were not nonsense Arabic as had been believed, but were written in a

romance language. (Samuel Stern, Les chansons mozarabes: les vers fin aux [kharjas] en espagnol dans les muwashshahs arabes et hébreux...,

Palermo 1953, reprint Oxford 1964). More recently, studies and

translations of Hispano-Arabic literature have proliferated — eg. Garcia

Gómez Todo Guzmán, and the exemplary anthology of James Monroe.

In 1922 a musicological controversy arose with the publication of the Arabist Julian Ribera's La música de las Cantigas (Madrid 1922), followed by La música andaluza medieval en las canciones de trovadores...,

3 vols, 1923-25. Ribera sought the rhythmic solution of the notation of

the Cantigas de Santa Maria in Arabic practices, a standpoint shared

with few music historians. The suggestion of some connection between the

Hispano-Arabic music and the Cantigas has remained alive in spite of

the negative reception of Ribera's thesis. Indeed, interaction between

the Moslem, Jewish and Christian civilizations has been studied

extensively in literature. Nyhl and later Briffault along with many

others defended the Arabic thesis of influence of the Arabs on courtly

love and troubadour lyric. Others supported the opposing theses of

classical heritage, while a few wrote about a spontaneous development.

Le Gentil in a little book about the villancico tried to present the

conflicting theses in perspective. In 1953 Samuel Stern published his

remarkable discovery that the final verses of the Andalusian muwashshahs

were not nonsense Arabic as had been believed, but were written in a

romance language. (Samuel Stern, Les chansons mozarabes: les vers fin aux [kharjas] en espagnol dans les muwashshahs arabes et hébreux...,

Palermo 1953, reprint Oxford 1964). More recently, studies and

translations of Hispano-Arabic literature have proliferated — eg. Garcia

Gómez Todo Guzmán, and the exemplary anthology of James Monroe.

The

existence of Christian-Moslem interaction in literature supports the

notion of interaction in other areas, including music. Whereas in

literature we have the written words in original manuscripts this is not

the case with music, which was largely an unwritten tradition in Spain

in the 13th century. Non-European traditions may shed light upon

important questions where documents are lacking. For example, in a

library of Valencia is the manuscript of a medieval Arabic cookbook from

Spain which purports to contain recipes by Ziryab, that original

musician, artist and bon vivant frequently credited with founding the

Spanish school of Arabic music. These recipes employ culinary techniques

and prepared “fonds” not adequately explained in the text. I was unable

to execute the recipes until James Monroe, who also knew the

manuscript, revealed his discovery to me, that through the study of

contemporary indigenous (i.e. non-French) cooking techniques from

Morocco the problems dissolved. If such study can help with the problems

of medieval cooking practice, perhaps it can help with the music too.

The Studio der frühen Musik (Early Music Quartet) undertook two

expeditions in the Maghreb (with the assistance of the German Goethe

Institute) in the 1960's, which were fruitful in the pursuit of elements

of musical performance practices relevant to the performance of Western

medieval monophony. The results have had a lasting influence on nearly

all subsequent performances of the monophonic repertory, either through

imitation, reflection or rejection. (viz. Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis 1; also

the recording Cantigas de Santa Maria, SCB-Documenta, harmonia mundi IC

065-99898 which reflects the Andalusian practice in the performance of

Cantigas).

There are two clear areas where the use of this

Andalusian music is appropriate as a model: performance techniques of an

instrument (all known to have been employed in the West) and the manner

of joining instruments together in the performance of monophonic music.

Of less direct importance are the specific improvisational models

pursued by the Andalusian players and singers, the manner of

constructing preludes, postludes and interludes, and the manner of

grouping poems together into suites accompanied by cyclic rhythms in

predetermined sequences. The origin of the specific repertory is not

relevant to this interest because it is not the material but how it is

presented that is important. It may be too late today to penetrate the

specific ties of this repertory to the medieval past. As we have seen so

often in this century, every erosion of a cultural border dilutes the

traditional music with exotic entries — new instruments, new rhythms, a

new sociology which all bring about irreversible changes in performance.

All

the more valuable, then, that this music has been captured on record,

an unalterable performance of a traditional music which has ties —

however elusive - to the Spanish Middle Ages.

Thomas Binkley

Moroccan music as an aid in the interpretation of medieval songs

The

present recording may be traced back to a “Woche der Begegnung — Musik

des Mittelmeerraumes und Musik des Mittelalters” (“A Week of Exploration

— Mediterranean Music and Medieval Music”) that was held in Basel from

January 31 to February 4, 1977. The focal point of this week was the

encounter of the “Studio der frühen Musik” (Andrea von Ramm, Thomas

Binkley, Richard Levitt and Sterling Jones) with the “Andalusian”

musical practice of North Africa as represented by a leading ensemble

from Fez under the direction of Hājj Abdelkarim Rais. The group's

musicological advisor was Hājj Idress Benjellun, director of the

Association of Friends of Andalusian Music in Morocco (jam‘iyatu hawāti

l-mūsiqū l-andalusīyati, magreb).

The “Woche der Begegnung” consisted

of several concerts performed by both groups, a workshop about the

“Andalusian” musical practice, as well as a musicological symposium

about the “Performance Practice of Medieval Songs” with Wulf Arlt,

Thomas Binkley, Josef Kuckertz (Cologne), Ernst Lichtenhahn, Hans Oesch,

Christopher Schmidt and Habib Hassan Touma (Berlin). The papers

presented at this symposium may be found in the Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis I (Amadeus-Verlag, Winterthur, 1977).

The

organizers of the “Woche der Begegnung” were the Schola Cantorum

Basiliensis and the Musicological Institute of the University of Basel

in collaboration with the Basel section of the Schweizerische

Musikforschende Gesellschaft and the Verein der Freunde alter Musik of

Basel.

The “Studio der frühen Musik” had the opportunity of

becoming acquainted with a musical practice which only recently has

departed from its unwritten tradition, as is the case with the

“Andalusian” music from Morocco, and of investigating how what they

learned could be used in their study of the performance practice of

non-liturgical, monophonic songs from the Middle Ages. Here the problem

lies in the realization of the extant written material — in which the

(relative) pitches of the monophonic melodies is notated and underlaid

with the text of one strophe of the song — in sound, a process involving

rhythmic specification, the textual underlay of further strophes of the

song and the addition of instruments. The “Andalusian” musical

practice, one which has an unwritten tradition, could be of assistance

here because of the geographical as well as the historical and cultural

connections between “Andalusian” music from Morocco and the medieval

song from southwest Europe. It is, however, particularly difficult to

reconstruct these connections in the field of music in that there is no

direct information from the Middle Ages about the “Andalusian” musical

practice, whereas the inverse holds for the material with which it is to

be compared. On the one hand our contact with the medieval song is

through an abstract notation, whose informational content is such that

our ability of producing an historically accurate realization is

limited, while, on the other hand, “Andalusian” music sounds today and

is a part of a musical tradition whose historical dimensions are far

from being clarified. The “Woche der Begegnung” thus remained an

experiment, one which by no means provided new solutions to the problems

of performance practice, but one, however, which made one aware of

those features, outside the realm of historical knowledge, of a real,

sounding musical practice which may have been lost.

“Andalusian” music

Recent

research about Arabic music distinguishes two main traditions of Arabic

art music, one associated with an eastern and the other with a western

region (Northwest Africa). In such studies the western tradition is

generally called “Andalusian” music under the justified assumption that

this art music now cultivated in North Africa was once an art whose home

was in southern Spain. Its origins, because of the occupation of the

Iberian peninsula by Islamic peoples (Arabian al-andalus, land of the wandalun,

of the Vandals), are thought to extend back to the court of [the]

Abbas[sids] in Baghdad. Reference is made, as direct evidence of such a

tradition, to a musician from Baghdad by the name of Ziryab who

emigrated to Spain in the 9th century and brought much innovation in the

field of music with him. The information in these sources concerning

matters of musical practice as well as of theory and terminology,

however, is totally inadequate for making a comparison with today's

musical practice. The first direct evidence we know of showing an

immediate connection with today's musical practice comes from the 17th

and 18th centuries. On the one hand this consists of the specification

of the names of the 24 keys by Muhammad al - būiSāmī (+ 1690) (Cf. the

Comments about the frontispiece) and, on the other, of the collection of

poems by muHammad al-Hā'ik, which was commissioned by the Moroccan

ruler, Muhammad b. ‘Abdallah (who reigned from 1757-1790). This

collection of song texts still constitutes the basic repertory of

“Andalusian” music today. A thorough study of the contents, a

classification of the repertory, as well as an identification of the

poets in the manuscripts, which are now mostly located in Morocco, all

have yet to be undertaken.

The repertory of “Andalusian” music

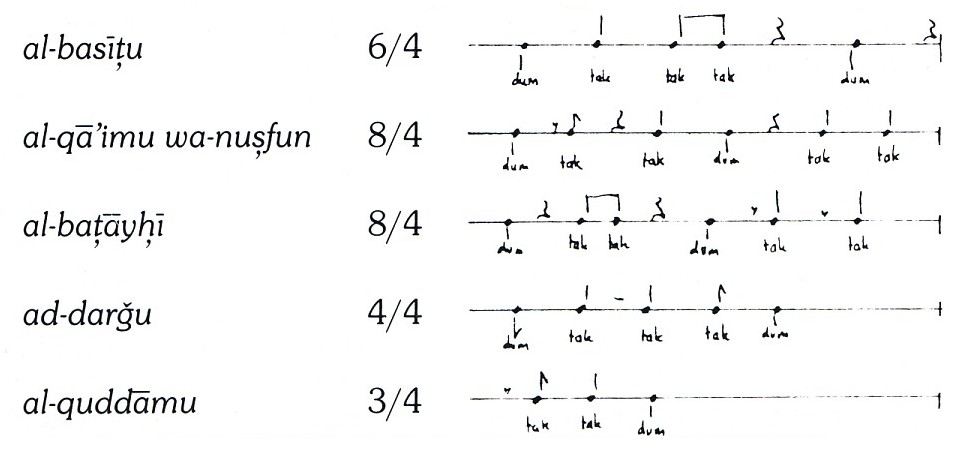

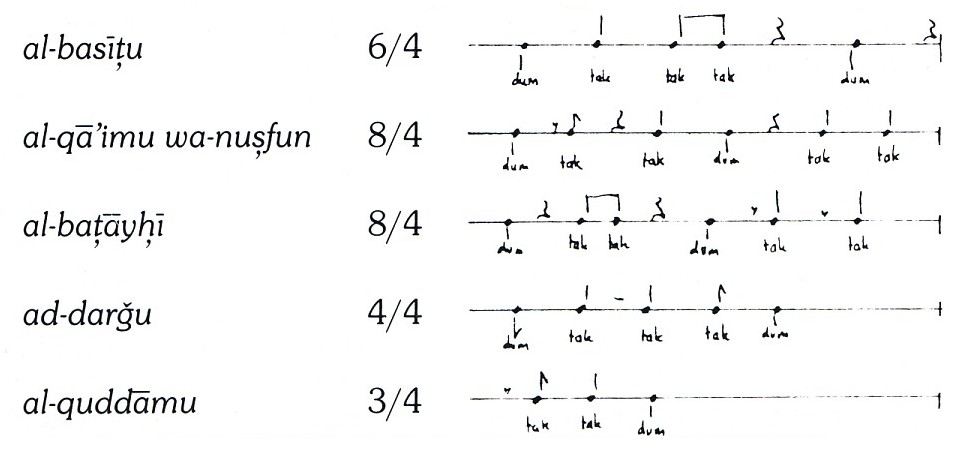

“Andalusian” music in Morocco has a clearly defined repertory which is subdivided into eleven sets of songs (so-called naubātun, sing.: naubatun) and instrumental pieces. In order to more explicitly specify a naubatun, the name of the key primarily used, such as al-māyatu, ar-raSdu, is appended. Further, each naubatun has 5 parts, whereby each part is accompanied by a basic rhythmic pattern (mizānun, pl.: mawāzinun). The parts are called by the names of these rhythmic patterns:

Basic form (“dum”: low note, “tak”: high note)

During

the performance of a section, the rhythmic pattern is played repeatedly

while the tempo is gradually being increased. On top of this framework,

songs (Sanā‘tu, sing.: San‘atun) with instrumental accompaniment are executed with instrumental preludes and interludes (tawshshiyatun). At the beginning of each naubatun there is an instrumental piece called a bugyatun which is tied to no rhythmic pattern. The bugyatun has the function of establishing the main melodic mode of the entire naubatun. Additional pieces, such as the baytāni and the mawwāl may be interpolated in the individual sections. The baytāni

is a vocal improvisation on two lines of text which is not tied to a

specific rhythm. The singer, in addition to the two lines of text, uses

the meaningless syllables “ha na na” to extend his improvisation. The mawwāl is an improvisation undertaken by the singer and the players of melodic instruments. Like the baytāni this improvisation is not tied to a rhythmic pattern and has the same improvisatory character. It differs from the baytāni

in that before and between the vocal sections, which are performed by

the singer alone, individual instrumentalists execute their own

improvisations.

The main components of each naubatun are the songs, muwashshahun and zajalun which have been set to music — poems which have been allotted to specific naubatun

on the basis of their content. Descriptions of nature, such as of

sunrises and sunsets or the beauty of plants, social gatherings over

wine, longing for one's distant lover, and praise for the Prophet

Muhammad are the main themes found in these poems.

As far as the

form is concerned, the musical settings of the poems are based upon

their strophic form; for the most part they have a seven-line strophe,

AABBBAA. This seven-line strophe consists of one three-line section,

which has a rhyme of its own (BBB), and of two two-line sections with a

rhyme in common (AA), which enclose the three-line section. Based upon

this strophic form, five-line poems are usually performed, ones which

lack the first two-line section (AA). This results in the rhyme scheme

of BBBAA. Subdivisions within the lines which coincide with internal

rhymes are significant in determining the form of the musical setting,

particularly in the first line of the two-line section. The individual

half lines and lines are thus associated with specific melodic sections

in a fixed order, whereby the following sequence is valid for the

strophic form BBBAA:

Melodic Section I: first line (B) and instrumental repetition

Melodic Section I: second line (B) and instrumental repetition

Melodic Section I: third line (B)

Melodic Section II: fourth line up to internal rhyme, instrumental repetition

Melodic Section II: second half of fourth line (A)

Melodic Section I: fifth line (A).

SCHOLA CANTORUM BASILIENSIS - DOCUMENTA

After

more than half a century the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis (SCB) and the

concept on which it is based have lost none of their relevance today.

Founded in 1933 by Paul Sacher, this “Lehr- und Forschungsinstitut für

alte Musik” at the Music Academy in Basle has remained unique in many

respects. From the time it opened until today, musicians prominent in

the development of the performance of early music, in which historical

practices are taken into account, have gathered together there.

Music

from the Middle Ages to the beginning of the 19th century is studied at

the SCB. Research, teaching, concerts, and publications are always

closely connected with one another because of the cooperation between

musicians and musicologists.

Some of the important subjects dealt

with at events and in editions sponsored by the SCB are preserved on

this series of recordings. The performers and the authors of the

commentaries are usually affiliated with the Institute.

The

purpose of the series is to document the significant initiatives made by

the SCB in the field of early music and to make them available to a

larger audience.

[CD]

[CD]

In 1922 a musicological controversy arose with the publication of the Arabist Julian Ribera's La música de las Cantigas (Madrid 1922), followed by La música andaluza medieval en las canciones de trovadores...,

3 vols, 1923-25. Ribera sought the rhythmic solution of the notation of

the Cantigas de Santa Maria in Arabic practices, a standpoint shared

with few music historians. The suggestion of some connection between the

Hispano-Arabic music and the Cantigas has remained alive in spite of

the negative reception of Ribera's thesis. Indeed, interaction between

the Moslem, Jewish and Christian civilizations has been studied

extensively in literature. Nyhl and later Briffault along with many

others defended the Arabic thesis of influence of the Arabs on courtly

love and troubadour lyric. Others supported the opposing theses of

classical heritage, while a few wrote about a spontaneous development.

Le Gentil in a little book about the villancico tried to present the

conflicting theses in perspective. In 1953 Samuel Stern published his

remarkable discovery that the final verses of the Andalusian muwashshahs

were not nonsense Arabic as had been believed, but were written in a

romance language. (Samuel Stern, Les chansons mozarabes: les vers fin aux [kharjas] en espagnol dans les muwashshahs arabes et hébreux...,

Palermo 1953, reprint Oxford 1964). More recently, studies and

translations of Hispano-Arabic literature have proliferated — eg. Garcia

Gómez Todo Guzmán, and the exemplary anthology of James Monroe.

In 1922 a musicological controversy arose with the publication of the Arabist Julian Ribera's La música de las Cantigas (Madrid 1922), followed by La música andaluza medieval en las canciones de trovadores...,

3 vols, 1923-25. Ribera sought the rhythmic solution of the notation of

the Cantigas de Santa Maria in Arabic practices, a standpoint shared

with few music historians. The suggestion of some connection between the

Hispano-Arabic music and the Cantigas has remained alive in spite of

the negative reception of Ribera's thesis. Indeed, interaction between

the Moslem, Jewish and Christian civilizations has been studied

extensively in literature. Nyhl and later Briffault along with many

others defended the Arabic thesis of influence of the Arabs on courtly

love and troubadour lyric. Others supported the opposing theses of

classical heritage, while a few wrote about a spontaneous development.

Le Gentil in a little book about the villancico tried to present the

conflicting theses in perspective. In 1953 Samuel Stern published his

remarkable discovery that the final verses of the Andalusian muwashshahs

were not nonsense Arabic as had been believed, but were written in a

romance language. (Samuel Stern, Les chansons mozarabes: les vers fin aux [kharjas] en espagnol dans les muwashshahs arabes et hébreux...,

Palermo 1953, reprint Oxford 1964). More recently, studies and

translations of Hispano-Arabic literature have proliferated — eg. Garcia

Gómez Todo Guzmán, and the exemplary anthology of James Monroe.