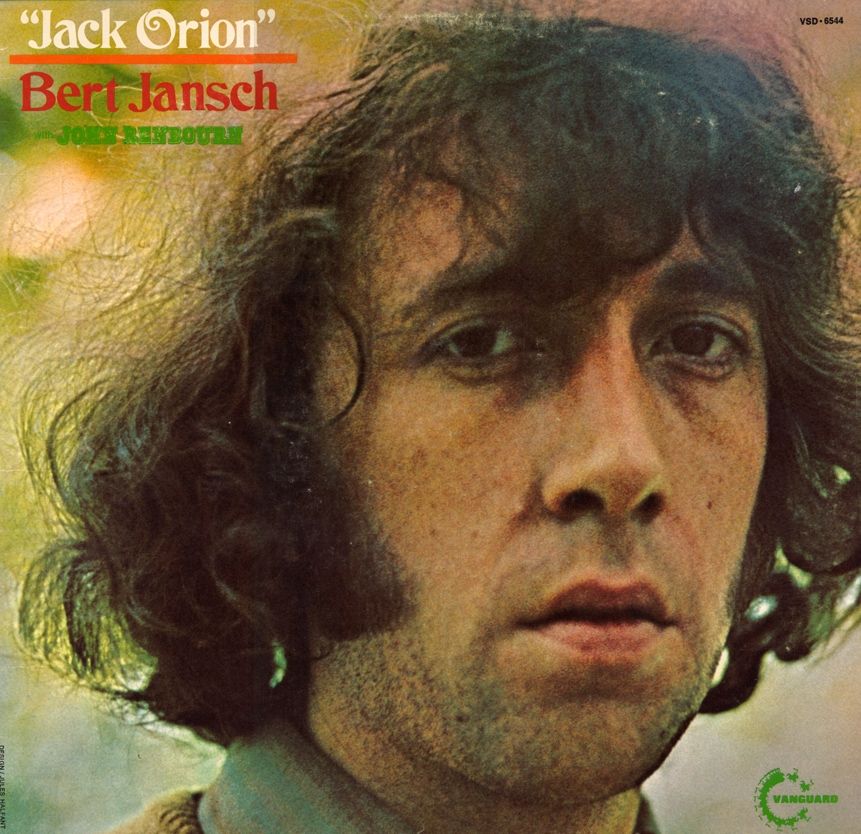

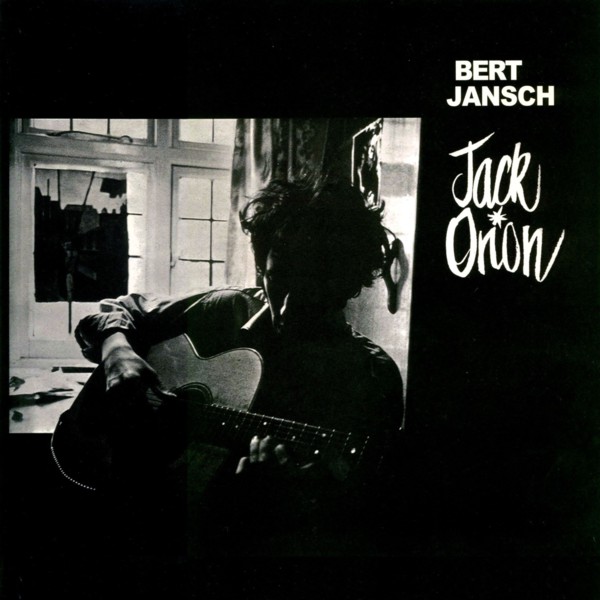

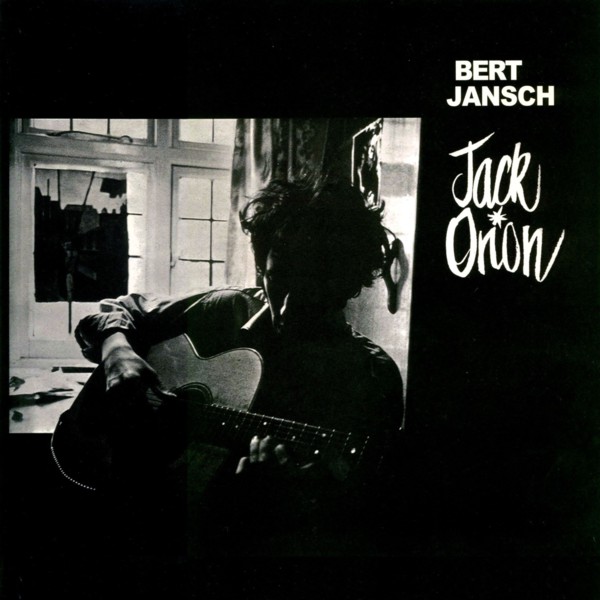

Bert Jansch - Jack Orion

amazon.com

bertjansch.com

Transatlantic TRA 143 (2001)

Recorded c. early summer 1966 at 5 North Villas, Camden, London

Varias ediciones, compilaciones (bertjansch.com)

A

1. The Waggoner's Lad [3:25]

2. The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face [1:41]

3. Jack Orion [9:46]

B

1. The Gardener [1:43]

2. Nottamun Town [4:34]

3. Henry Martin [3:11]

4. Blackwaterside [3:44]

5. Pretty Polly [4:00]

(Trad., Arr. Jansch, excepto A.2: McColl)

Bert Jansch, guitar, banjo, vocal

John Renbourn, second guitar on A.1 A.3 / B.3 B.5

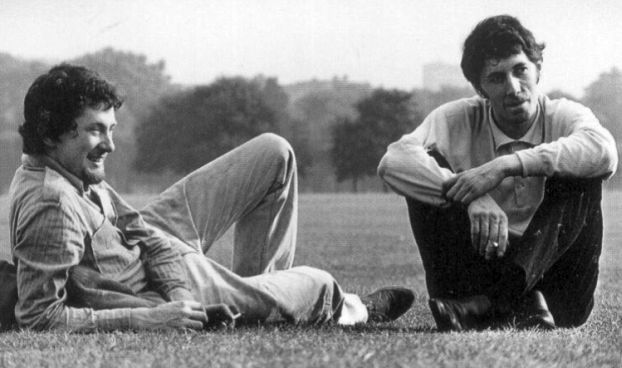

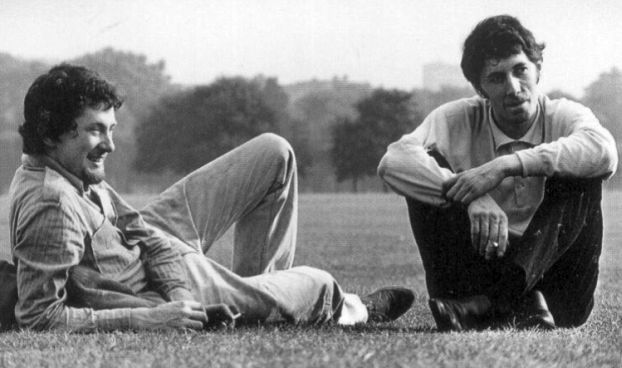

By the beginning of 1966 Bert Jansch,

his flatmate and occasional performing partner John Renboum and their

musical mentor Davy Graham were all perceived as a quite distinctive

by-product of the British folk revival, and their technical

accomplishments were taken as read. "They've proved that they can exist

as an independent 'third stream', influenced by both folk and jazz,"

wrote Karl Dallas in Melody Maker. "They've now got to produce

some really memorable music that stands up on its own account."

Following his initial breakthrough the previous year, not only as an

instrumentalist but as a songwriter of stark originality with songs

like 'Needle Of Death" which seemed to speak to a generation, Bert's

next significant progression was to be found in his

third album Jack Orion - a brooding, intense and deeply

individual approach to the British and Irish tradition. Fine though

they were, his second album It Don't Bother Me had simply

pursued the songwriting idiom of Bert Jansch - more robust and

self-confident perhaps, though necessarily lacking its predecessor's

element of surprise - while his jointly-billed collaboration with

Renbourn, Bert And John (released simultaneously with Jack

Orion in September 1966) was essentially an exploration of

jazz-based ideas that would see fruition a year or two down the line

with the formation of folk-jazz fusion pioneers The Pentangle.

Having found the 'real studio' work for It Don't Bother Me a

pressurised experience, both Bert And John and Jack Orion

would be recorded by Bill Leader in the front room of the pair's flat

at 23 St. Edmund's Terrace. Completing the picture with Renbourn second

solo album, Another Monday (recorded at Leader's place during

that summer of '66), here were three albums bursting with ideas and

addressing Karl Dallas's challenge in striving for something musically

substantial out of what was still a novel and embryonic genre

dangerously close to being perceived as delighted by its own ability.

Each of the three albums were viewed individually and with the luxury

of time - and these were, let us not forget, albums recorded in little

more than an afternoon - may reveal imperfections in execution, scope

or variety yet taken together they present a musical jigsaw of

extraordinary inventiveness and imagination. Modern jazz, European

baroque, American hillbilly, Dylanesque contemporary songs and,

exemplified most startlingly on Jack Orion, British and

Irish traditional music were all facets to be singularly mastered and

woven together.

Though featuring Renbourn on four tracks, Jack Orion was

the product of ideas that had been brewing in Bert's mind alone and

fermenting in his playing style for the previous year or more, and was

consequently the most focused, taut and energized product of the

trilogy. Its impact was immense Bert had at last committed to record

the first fruits of the explorations with traditional music, relying

exclusively on DADGAD or 'dropped D' tunings, that he had begun with

his friend Anne Briggs - the now legendary English traditional singer -

before even his first album had been released. An element of

synchronicity had been involved, as both were in London with a little

time to kill during the early weeks of 1965 and with a mutual friend in

Gill Cook whose flat was free during the day:

"Bert would come around to Gill's flat when there was nothing else to

do," says Anne, "and we'd work together for our own personal interest

on traditional songs, with his dramatic guitar playing. We discovered

that they could really gel together. Once he started elaborating on

what I'd come up with I had to move fast to keep up, so it really

brought my guitar playing along. He'd write a verse, I'd write a verse.

I'd come up with a tune, he'd play it, and he'd elaborate on it. It was

a very creative period but it only went on for a very short time." The

process was almost accidental, to Anne's recollection "There was a lot

of stuff that just drifted away - if it wasn't together by the end of

the afternoon, forget about it". But three original songs survived, to

filter out on albums by both Bert and Anne individually between

1966-71: 'Go Your Way, My Love', 'Wishing Well' and 'The Time Has

Come'. The last track was composed by Anne alone, the others jointly,

but all three combined otherworldliness, foreboding and melancholy and

were quite unprecedented in any genre of popular music.

More important than the quality of the songs written together, however,

was the development of a new approach to accompanying traditional music

- superficially similar to that explored by the relatively short-lived

Shirley Collins/Davy Graham project (which resulted in the album Folk

Row Neal Routes, coincidentally released during the Jansch/Briggs

writing sessions) but free-er of form, looser in feel and as sensual

and fresh as the content of the first song it was designed for the

one-night-stand Irish ballad 'Blackwaterside'. For all the rivalry that

would develop between Jansch and Graham over the next few years, real

or imagined, Graham would come to regard 'Blackwaterside' at the very

least as "a masterpiece of its kind, and I do not use that word

loosely".

"All the traditional singers I knew at the time, like Jimmy MacBeath

and Jeannie Robertson," says Bert, "were older people and you couldn't

exactly say, 'Could you just slow that down and repeat that verse?' But

Anne, because she knew all these songs, I could quite happily get her

to sit and go over the likes of 'Blackwaterside' a few times until I'd

worked out how to do it on the guitar. This was the first time I'd ever

actually sat down and taken a folk song other than a Woody Guthrie-type

song - a number that bad a definite melody line that I couldn't change

- and consciously created a backing to go with it."

"He had always had a real feeling for traditional music," says Anne,

"but when I first knew him he just didn't think he had the right sort

of voice and couldn't use the guitar in the right way to be a singer of

traditional songs himself. By this time he'd become a much

sophisticated player, and I think he had the confidence to handle it.

Everybody up to that point was accompanying traditional songs in a very

Woody Guthrie, three-chord way. I was never happy with that - not in an

academic sense, just aesthetically. It was why I always sang

unaccompanied. I'd played guitar since I was fourteen or fifteen but

seeing Bert's freedom from chords I suddenly realised that this chord

stuff — you don't need it."

They were exciting discoveries: "I was pregnant at the time but working

very hard in the shop," says Gill Cook, an assistant at the specialist

record shop Collet's, "and I can remember them ringing up and saying,

'Hey, we've just written a song!'" Bert and Anne never performed their

new songs or traditional settings together at that time. To Bert's mind

they were simply "too erratic to get it together"; to Anne's, it was a

case of audiences perceiving them as entirely unrelated performers. For

all her new-found freedoms as an instrumentalist using alternate

tunings learnt from Bert - Graham's DADGAD and the DADGBE of

'Blackwaterside' - Anne would not have the confidence to use a guitar

onstage for same years yet. It is not known when Bert debuted the

ground-breaking 'Blackwaterside' onstage, but it would have to wait a

year and a half to appear on record.

"Jack Orion really turned people upside down," says

Martin Carthy. "Bert And John not so much. At the time, Jack

Orion was the one where people just sat back and thought, 'What

is he trying to do?' It was just so outrageous and different, so unlike

anything else that anybody else had ever played - and the title track

was nine minutes long! For us twenty to twenty-five year-olds ballads

were still boring things which you had to get down to as few verses as

possible. We didn't actually understand this idea that it's not a

question of how long a ballad is, it's the fact that it does so much in

such a short space of time: so it's thirty verses and ten minutes long

- that's two and a half hours in a film. And if you give it just as

much concentration as you give a film you're going to be just as

excited."

'Jack Orion' itself was the vestige of a traditional melody,

reconstructed by folklorist Bert Lloyd as a narrative on the sexually

charged adventures of a demonic fiddler. Bert Jansch's version

succeeded more through the intensity of performance than through any

great accuracy in execution: this was a relentlessly dark, dense

assault upon the hallowed tradition. Other tracks, however 'Trad Arr.'

in their credits, were vehicles for the scattergun imagination behind

Bert's instrumental work. His interpretation of 'The Gardener' (a

ballad sometimes referred to as 'The Gardener's Child'), a song learned

from his Edinburgh friend Owen Hand, was wildly impressionistic - a

wordless vocal scatting some rumour of the song's melody atop a

cyclical, string-snapping riff which reappeared in the arrangements of

Ewan MacColl's 'The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face' (sensitively

performed, and a moment of light in the modal darkness) and the

immortal 'Blackwaterside'.

That song at least, by far the most crafted piece on the record, had

already been played around the clubs. Fellow singer-songwriter Al

Stewart had been following Bert around, keenly observing this

revolutionary new playing style and determined to master it. A few

weeks before Jack Orion appeared, Al had booked a studio

and session players to make his own record debut. Jimmy Page, an

established sessioneer, timed up to play guitar and during a tea-break

Al played him Bert's accompaniment for 'Blackwaterside'. It was

possibly Page's first acquaintance with the DADGAD tuning, and the

seeds were sown of what would later become a distinctively folky,

eastern-influenced but very British element in mainstream seventies

rock that would have wide-ranging reverberations in that world.

In his subsequent capacity as a member of Led Zeppelin, the biggest

rock group of the seventies, Page would be enthusing wildly on the

topic of Jansch for years to come: "A real dream-weaver," he said. "At

one period I was absolutely obsessed by Bert Jansch. I watched him

playing once at a folk club and it was like seeing a classical

guitarist. All the inversions he was playing were unrecognizable. He

was the innovator of the time."

"I don't recall being shocked," says Transatlantic label boss Nat

Joseph, on checking out Bert's new sound for himself. "I was never

shocked when I heard anything other than when it was very bad. Bringing

in the traditional material was something that seemed to me extremely

interesting because everybody had thought of Bert as a kind of

Dylanesque character. He was going back to the roots and I couldn't see

why no."

"The treatments may not be trad but they're fantastic," agreed the

reviewer for Sing. 'At first sight the idea is horrifying,"

cautioned Karl Dallas in MM, "a bluesy guitarist who has

hitherto concentrated on contemporary subjects singing the big old

ballads of the true traditionalist. In fact, Jansch's interpretations

illuminate the songs from a completely new angle. As sung by him, the

brutal world that created the old ballads doesn't seem so very far off

from the world of the 'Needle Of Death'."

Colin Harper, July 2001 - author of Dazzling Stranger: Bert

Jansch and the British Folk and Blues Revival (Bloomsbury, 2000)