Iacobus. Codex Calixtinus, Omnia Cantica

Coro Ultreia — Liner notes

Iacobus

Codex Calixtinus

Religious Poetry in the Codex Calixtinus

The Codex Calixtinus, Compostelan Liturgical Landmark

Europe's Founding Song

The Sound of the Codex

IACOBUS

IACOBUS

To my father.

To our fellow Benito.

To Maruxa Barreiro.

Just

as Master Mateo's “Pórtico da Gloria” (“Gates of Glory”) in the

Cathedral of Santiago stands as a true jewel of medieval Christian art,

so the Codex Calixtinus or Liber Sancti Iacobi kept in the Cathedral's

library can be considered a genuine historical, literary, liturgical and

musical monument. Its importance is reflected in the various articles

from this booklet accompanying our full recording of the music from the

manuscript, whose very prologue bears the name IACOBUS.

Our

choir's name gives away our interest for this invaluable musical

repertoire. As for myself, this interpretative endeavour derives from my

fondness and liking for the Jacobean phenomenon. But it is also the

result of my own scholarly and interpretative experience of the

Calixtinus's music, gathered from the almost fifteen years during which I

was lucky enough to belong to the Chamber Group of the University of

Santiago de Compostela. Under the direction of Carlos Villanueva, I

became familiar with Prof. López Calo's work, which is no doubt the

touchstone of all musicological research on the Codex. This activity,

which was rendered into many live performances and musical recordings,

was continued when the Ultreia Choir came into being under Vicente

Couceiro's direction. No wonder, then, that in the course of these years

and looking ahead on the oncoming last Jubilee of the millenium, we

devised this ambitious project that finally comes to light after two

long years of work.

The paleographical basis for our

interpretation is the Codex itself, particularly the excellent full

edition by Dom. Germán de Prado accompanying the masterful research work

on the Liber undertaken from 1931 to 1944 and sponsored by the Consejo

Superior de Investigaciones Científicas and the Instituto P. Sarmiento

de Estudios Gallegos. According to the suggestions from this outstanding

musicologist from Silos, we include all the music contained in the

manuscript except for that which, even though mentioned in the incipit,

is not complete or does not belong to this specific repertoire (ie. the

psalms).

The monody throughout Book I displays a great variety

and richness of melodies. The fact that many of these tunes were already

known and had been taken from other choir books and musical

compilations (Benedictine Antiphonary, Roman Antiphonary, etc.) does not

diminish the musical value of this beautiful repertoire. The adaptation

of preexistent melodies (through centos or contrafattura)

was already a long-standing custom in ancient musical practice, and

there was no need for the compiler of the Codex to do differently. In

any case, the outcome of this adaptation of ancient liturgical texts is

splendid, and it stands far above most medieval repertoires devoted to

one single figure. The process was reversed in some cases, as with the

pretty tune “O lux Decus Hispanie” which can be found in many

manuscripts afterwards.

Leaving aside any musicological

disquisitions about its authorship, origin, or intention, or about the

overt French influence on the Codex's style and notation, or about

whether this or that lyrical or musical component had already been used,

our impression as interpreters of the Codex is that we face a body of

music to be used in the worship of the Apostle, whether this be in the

Cathedral of Santiago itself or in some other church. This would refute

other readings which consider it a French didactic manual, strictly for

teaching. The importance of the music, the numerous indications for its

proper use that can be found in the very text (like “St James's own mass

must be sung every day to the pilgrims;” “This to be sung by a child

standing between the Reader and Singer;” “This to be sung joyfully;”

etc.), as well as the opinion of authoritative scholars all support the

specific Jacobean end of this music. This monody comprises mainly songs

for the offices for St James (invitatories, hymns, antiphons, responses,

lessons, chapters and verses), processional verses, and three masses,

one for the vigil and two for the feasts of St James, one of which is

the original farce mass with tropes for every part but the Crede. The

pieces were ordered numerically, as in the Roman Antiphonary. Our

interpretation followed the free and loose rhythms indicated by the

tunes themselves—which have a marked melismatic character—, so that we

could enjoy some freedom of style in our performance. We have also felt

free to use some polyphonic techniques such as pedal notes or bordons,

which come from improvisational procedures like the faux-bourdons. This

has enriched the plain chant and has readied us for what is the most

interesting and famous instance of musical art in the Codex: the

polyphonic compositions which, except for two of them, are collected in

the appendix at the end of Book V. These are liturgical and processional

pieces such as conducti, organa, etc. which make up “the first

polyphonic repertoire of artistic value in the History of Music”, as

Professor López Calo has asserted. Following both this scholar's work

and our own experience, we have avoided sticking to any aprioristic or

preconceived theory attempting to solve the musical problems raised by

the polyphony in the Calixtinus. The balance between the looseness and

freedom of the musical phrasing, and the rigour in the polyphonic

setting of the voices can only be achieved by means of the detailed

analysis and interpretive study of each individual piece, of its

internal rhythm and of its melodic singularities.

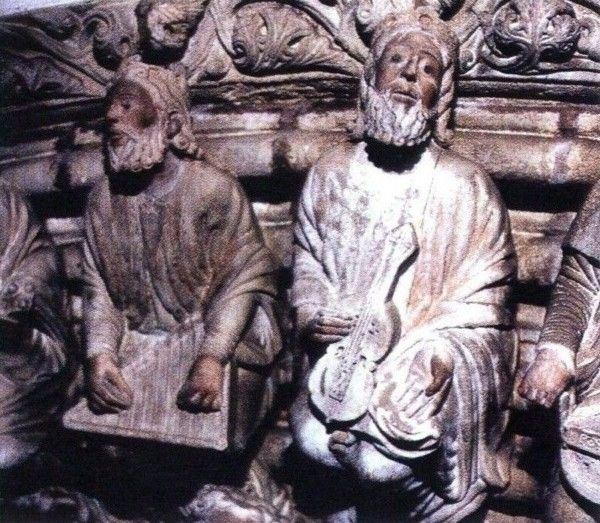

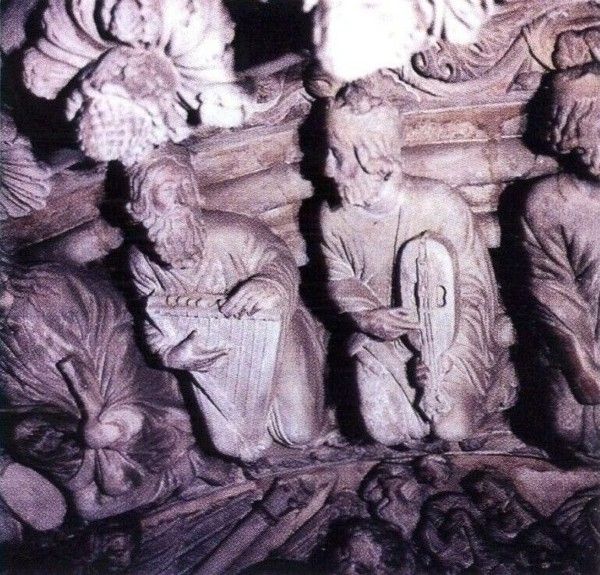

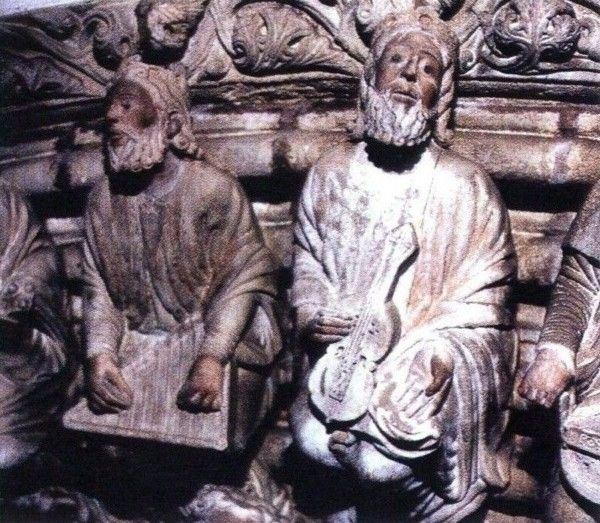

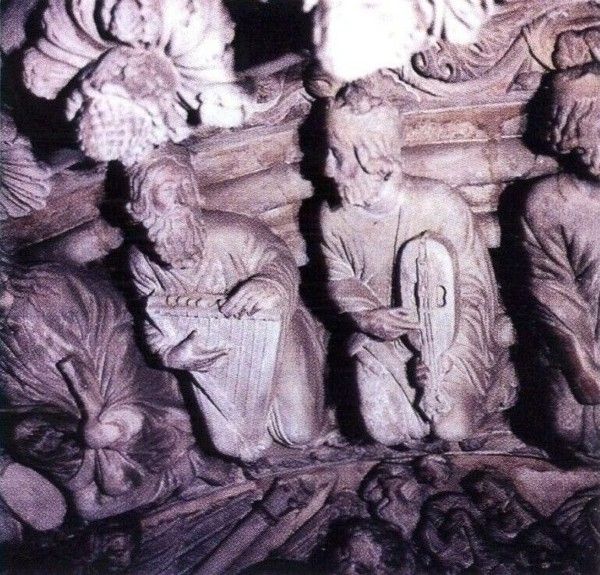

The

accompaniment by instruments is justified for two reasons: firstly

because of the plentiful literary references in the Codex; and secondly

because the instruments used in the recording are replicas crafted after

the marvellous stone rendering of contemporary instruments in the

“Portico da Gloria”. Provided by the Compostelan group Martin Codax,

these instruments evoke the sonority that this music could have had

under the vaults of the Apostolic See.

Let me finish the

introduction to this booklet by thanking the help and contribution from

many people and institutions listed elsewhere, and especially from our

Lord St James. Indeed His aid has made it easier for us to record the

music from “His” book.

Pontevedra, March 1999, in the Holy Year of St James

Fernando Olbés Durán

CODEX CALIXTINUS

By Emilio Casares Rodicio

The

“flaming lights” that could be seen at night over the Celtic village

near Iris Flavia were the sign that convinced bishop Teodomiro and king

Alfonso II “the Chaste” that St James the Apostle's remains were buried

on that very spot. Such a miracle soon prompted the building of the

first places for worship, paid for with royal funding. These

constructions would eventually become the city called Compostela,

“campus stellae”, in remembrance of those lights. The news about the

finding of St James's corpse spread rapidly around all Christendom, and

both the Pope and Charlemagne—as would the order of Cluny later

on—became involved with fostering the appeal of the sacred place. In

fact, the story goes that the son of Pipino's contribution to the

pilgrimage to Santiago went as far as to build the basilica of Sahagún

or the Way of Santiago, and even to discover the Apostle's sepulchre.

The faraway Compostela of St James—the only Apostle to be buried in

Western Europe except for the martyrs of Rome—would become the western

vertex of Christian pilgrimage, particularly since visiting the Holy

Places under Islamic rule turned out to be a dangerous endeavour.

More

stars, like the ones in the Milky Way, have helped the pilgrim trod his

way to Santiago to this very day. Every year, thousands of pilgrims

from all around the world come to Santiago following the path that runs

along the way of the stars in the sky. As they linger on their way, they

leave samples of their art, their science, or their language. There is

no way to account for what the thrive and exchange brought about by the

pilgrimage to Santiago has meant to the development, culture and art of

the Iberian Peninsula.

Such a remarkable event was bound to give

rise to works of literature for the pilgrims and about their pilgrimage.

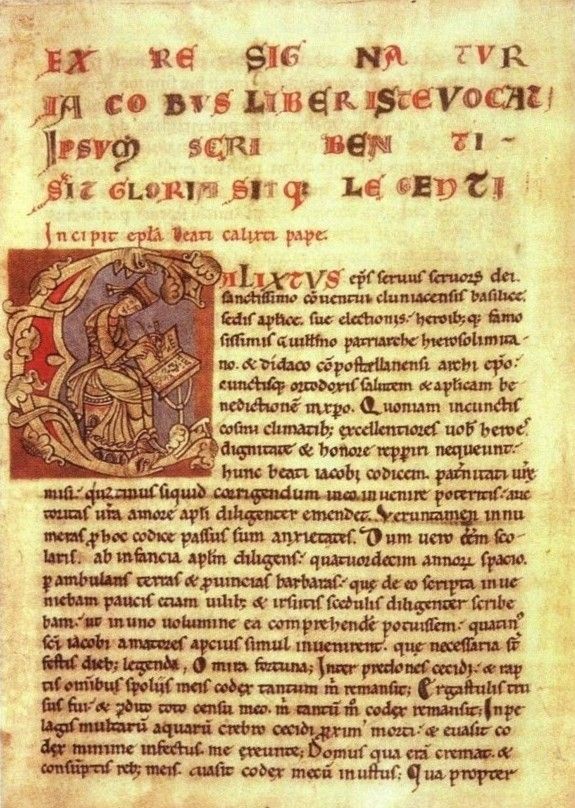

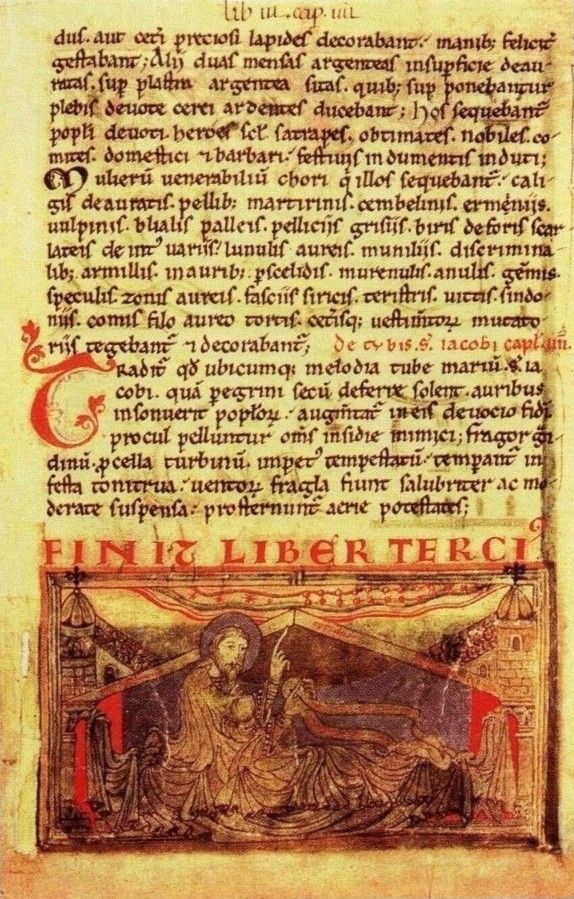

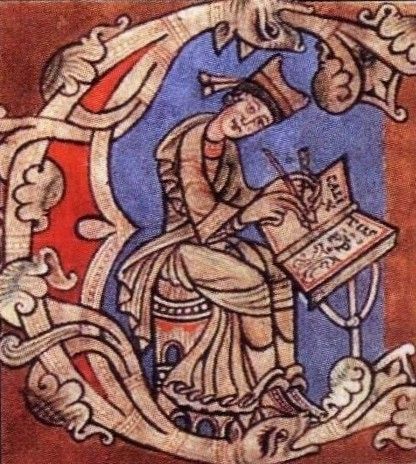

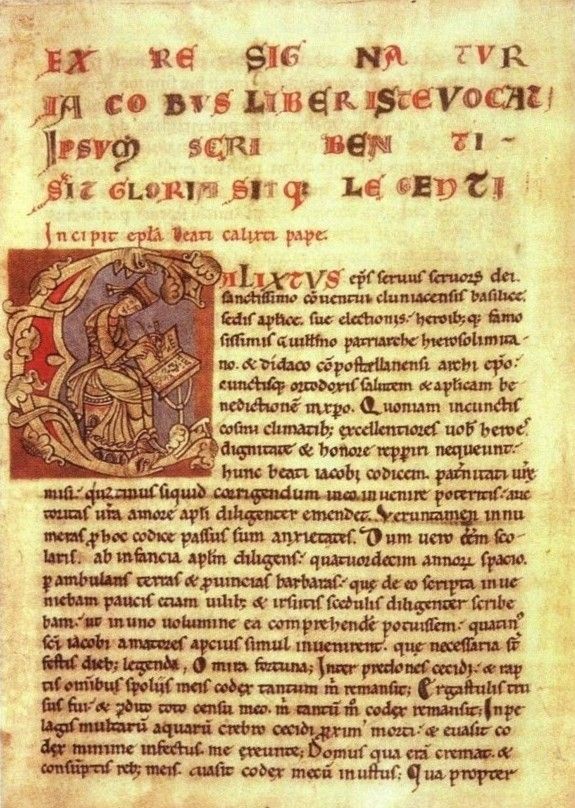

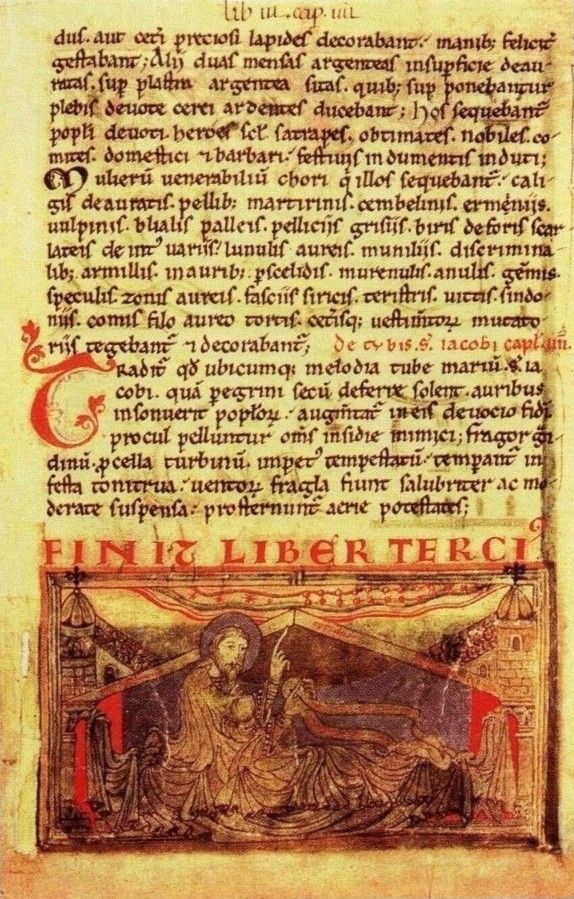

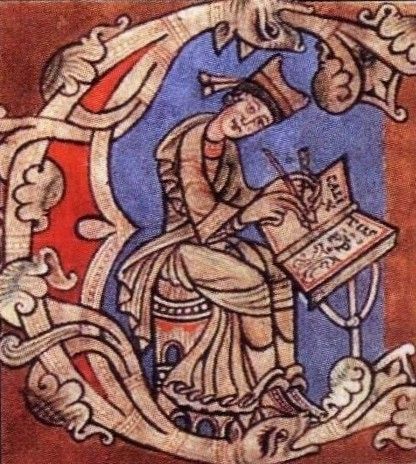

One of the seminal works is no doubt the Codex Calixtinus, known since

the beginning of this century also as Liber Sancti Jacobi, the very

first words in the text. The manuscript is kept in the archive of the

Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. It was copied with extreme care on

fine parchment, and it is adorned with beautiful miniatures and

initials. It comprises a collection of services, sermons or chants in

honour of St James the Apostle, who is the saint patron to the

cathedral.

The Calixtinus—so called because most of the

pieces in it were attributed to Pope Calixtus II— was compiled at the

start of the last third of the 12th century (probably in 1160 to 1170)

with materials of varied origin and authorship. Dr. Lopez Calo asserts

that the materials in the Calixtinus were written before they were ever

included in the Codex, though immediately before, “so that only a few

years could have passed between the writing and compilation of these

materials and their inclusion in this and other extant copies of the

Liber Sancti Iacobi. It can be ascertained that the idea of compiling

these writings in honour of St James the Apostle came about in the time

of bishop Diego Gelmírez, more exactly from c. 1120 on. This means that

the Codex was but one more of the many endeavours conceived and

undertaken by the great Compostelan prelate in order to exalt his church

and to present an audience as large as possible with the excellence of

the Apostle, of his worship and of the city that held its remains”. Calo

continues: “although the text was the work of several copyists, most of

it was carried out by one single scribe who worked under heavy French

influence, probably Cluniac”. Indeed, Gelmírez brought in the most

outstanding representatives of culture at the time, Cluny monks, for he

believed this would raise the cultural level in Santiago. That is why

most of the writing and musical notation of the Codex are French, more

precisely Northern French.

The Calixtinus—so called because most of the

pieces in it were attributed to Pope Calixtus II— was compiled at the

start of the last third of the 12th century (probably in 1160 to 1170)

with materials of varied origin and authorship. Dr. Lopez Calo asserts

that the materials in the Calixtinus were written before they were ever

included in the Codex, though immediately before, “so that only a few

years could have passed between the writing and compilation of these

materials and their inclusion in this and other extant copies of the

Liber Sancti Iacobi. It can be ascertained that the idea of compiling

these writings in honour of St James the Apostle came about in the time

of bishop Diego Gelmírez, more exactly from c. 1120 on. This means that

the Codex was but one more of the many endeavours conceived and

undertaken by the great Compostelan prelate in order to exalt his church

and to present an audience as large as possible with the excellence of

the Apostle, of his worship and of the city that held its remains”. Calo

continues: “although the text was the work of several copyists, most of

it was carried out by one single scribe who worked under heavy French

influence, probably Cluniac”. Indeed, Gelmírez brought in the most

outstanding representatives of culture at the time, Cluny monks, for he

believed this would raise the cultural level in Santiago. That is why

most of the writing and musical notation of the Codex are French, more

precisely Northern French.

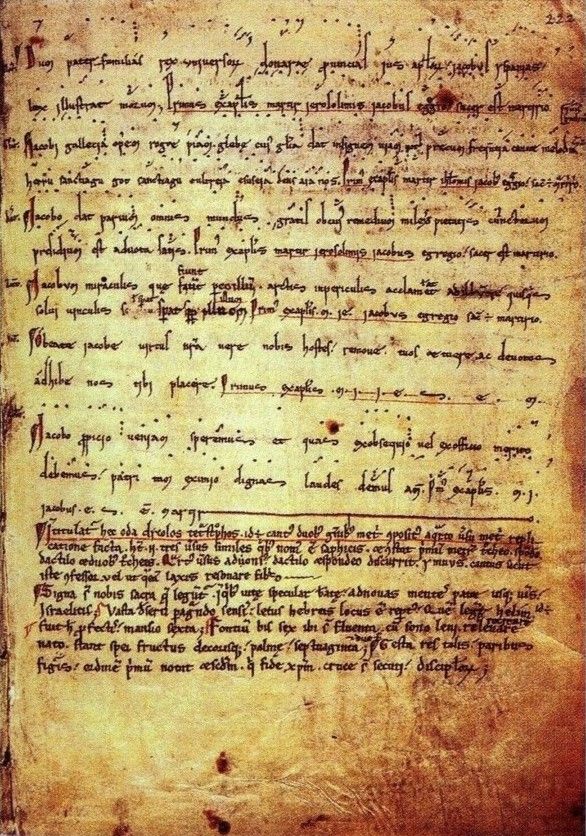

The Codex is made up of five books of

uneven value. The first one is the most interesting one, for it

comprises the liturgical ritual for the various festivities pertaining

to St James together with a great number of monodic compositions for the

various parts of the services, as well as numerous conducti, proses,

farces, etc. One short booklet is particularly interesting music-wise,

for it comprises 22 polyphonic pieces from as early as the very

beginnings of the Ars Antiqua. The booklet was added to the Codex after

it had been completed (López Calo's estimation is no later than 1180),

and it includes the conductus, the earliest known composition for three

real voices.

Thus, the Calixtinus stands as the oldest and most

coherent whole musical corpus in Europe: it comprises the complete

liturgy and its music, together with the chanted pieces for the

services; it also includes masses, many of which are well-known, and

other poetical works to adorn different moments of the ritual (fol. 123r

and ff.). The liturgy in the Cathedral of Santiago appears as one of

the most magnificent in Western Europe. The music resounded in the

Cathedral of Santiago all day long: ordinary and feast masses and

services, eve songs of praise and pilgrimage by English, Germans,

Italians, French. On arriving, the worshippers of the Apostle went into a

superb Romanesque church and attended a splendid liturgy, adorned with

chants enriched by tropes and proses and conducti written purposely for

the liturgy of the saint patron and dedicated to him. The modern verse

forms with their rhythmic scansion and polyphonic accompaniment sung by

the Cathedral school and musicians alternated with more popular songs in

honour of St James that the pilgrims would play on their own

instruments and in their own languages. A musical symbiosis occurred,

mingling the whole culture of the Middle Ages in Western Europe.

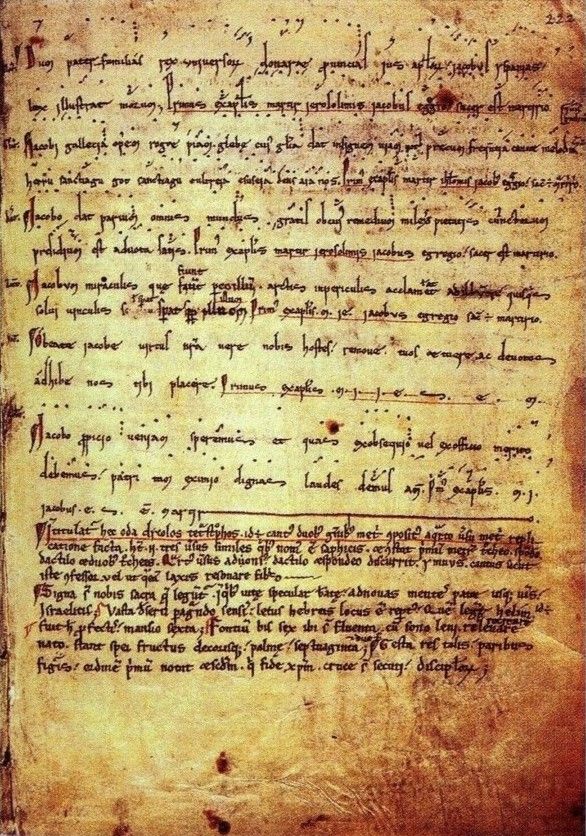

But

there was singing all along the journey, too. Popular songs from the

Peninsula would be played and sung at resting stops, which in many cases

took place the at Clunian monasteries open to pilgrims. The pilgrims

would cry “Eia, ultreia!” when they reached the Monte do Gozo (”Mount of

Joy”) and saw Santiago for the first time. Together with other popular

or clearly foreign expressions from pilgrimage songs, this cry appears

in several occasions in the Calixtinus, for instance “ultreia” in Alleluia Gratulemur (f. 120v), in Ad honorem regis summi (f. 199v), and in Dum pater familias (f. 193r), in which we also find “Herru Sanctiagu, Grot Sanctiagu” (”Lord St James, Divine St James”).

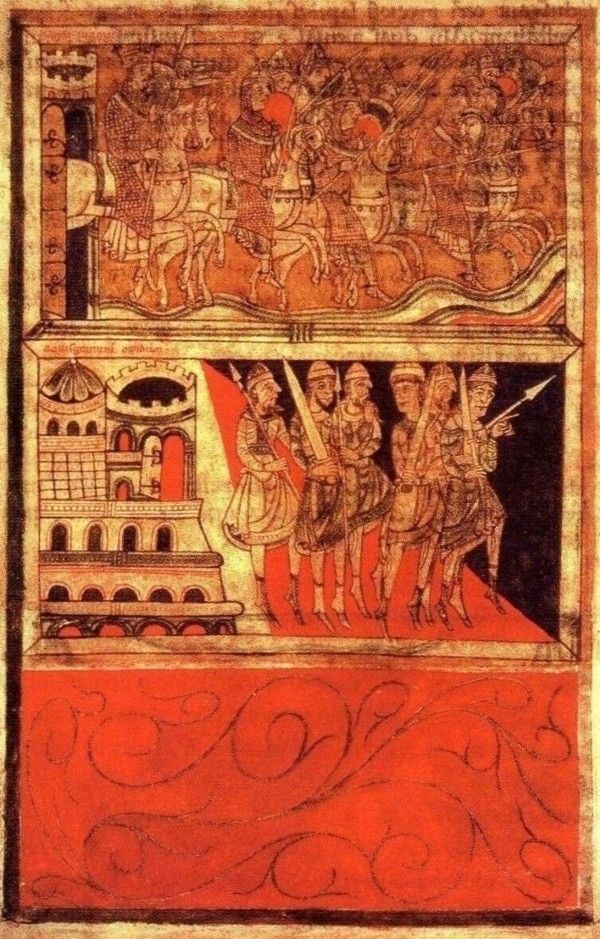

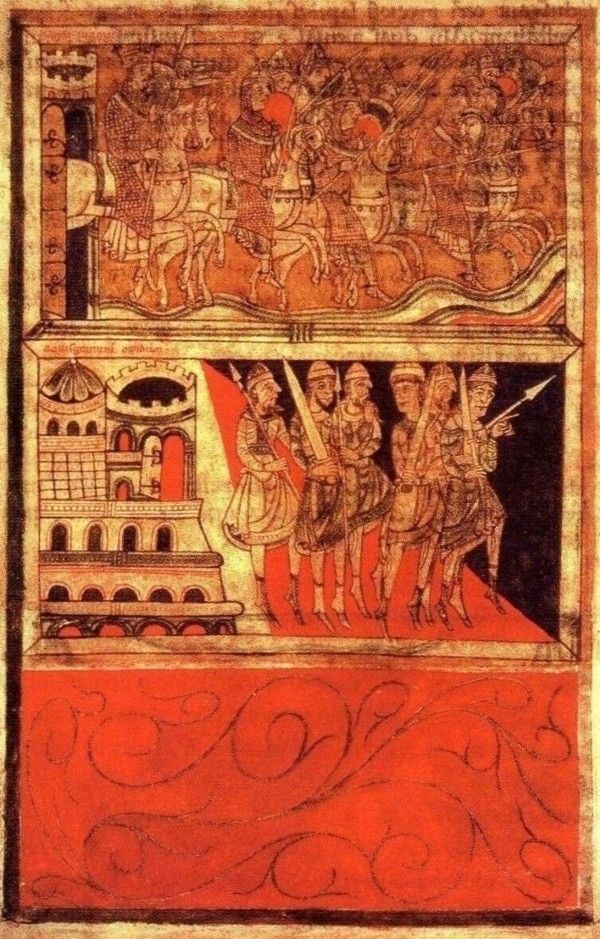

Apart from music, the Codex Calixtinus

comprises many useful news for the faithful and for pilgrims such as

tales about the Apostle's miracles or the Bearing of his corpse, the

narrative of Charlemagne's crusade in Spain (known as the

“Pseudo-Turpin” after its presumed narrator), a collection of liturgical

and ritual texts, and the Liber Peregrinationis containing ample

information about the journey. It seems, then, that the work had a

twofold purpose: to exalt and spread knowledge about the Compostelan

see, and to provide the pilgrims with information and teachings about

it.

Most certainly, any work written in Santiago in the course of

the 12th century might well have been the work of a Frenchman, or of

someone under heavy French influence. The rubrics of the musical pieces

in the Calixtinus name numerous French ecclesiastics as authors (also

Italians and some Galicians, but mainly French): Ato, bishop of Troyes;

Gauterius of Château-Renard; Magister Golsenus, bishop of Soissons;

Droardus of Troyes; Fulbertus, bishop of Chartres; Magister Albertus of

Paris; Magister Albericus, archbishop of Bourges; Magister Airardus of

Vézelay. Most of them are known and some of them certainly as composers,

but still the attribution of many of the pieces in the Liber Sancti

Iacobi is doubtful. Nevertheless, many pieces show a strong local

influence in the form of direct references to rituals and places, and

sometimes even in the use of popular melodic twists1: there is no doubt whatsoever that the manuscript was written for the Cathedral of Santiago and its services.

It

has already been pointed out that the most conspicuous part of the

Calixtinus is its polyphonic booklet (ff. 185r to 192r), which is the

first written European polyphony together with that of Saint Martial of

Limoges. Fairly enough, it has been considered the most important

section in the Codex.

The birth of polyphony is one of the great

revolutions in the history of music. Some musicologists have even

posited the hypothesis that the true beginnings of western music were

tied to the appearance of this musical technique. They argue that

monodic music—one-voice singing—would be an eastern tradition which had

been transplanted into the western world. In Europe, however, there

comes a time at around the 9th century when a new perspective on music

arises, and polyphonic singing comes into being. Through it will the

western man find a way to reach over the straightforward preexistent

musical forms—which were no other than Gregorian chant—and develop a new

feel for music. Containing some precious tokens of this primitive

polyphony, the Codex Calixtinus was not only a witness to this revolution, but also a force in it.

Both

rhythmically and compositionally, the Calixtinus steps ahead of works

from the school of Limoges, standing halfway between it and the

so-called school of Notre Dame of Paris—it should not be forgotten that,

among its many authors, our work names some master Albertus of Paris,

likely predecessor of the Master of León, Leoninus.

This is how

Professor Lopez Calo describes the music from the Calixtinus: “The

polyphony in the Calixtinus would be halfway between the free rhythm of

plain chant and the strict rhythm of the Ars Antiqua, measured according

to the rules of the six modes. Still, it is obvious that the polyphony

in the Codex Calixtinus stands as the first polyphonic repertoire of

artistic value in the history of music after the theoretical experiments

from the 10th and 11th centuries and conducti from Winchester and St

Martial, which cannot be compared, artistically speaking, to the

Compostelan compositions”. Clearly the Schools of Santiago and Limoges

are the two great representatives of 12th century polyphony, and the

three-voiced polyphonic pieces in the Codex Calixtinus and in the work

from St Martial are one of the keystones of medieval polyphony. There

has been discussion about who influenced whom, but there is no doubt

that Santiago was the great disseminator by means of the musical

activism that springed from the Way and rests on a beautiful and

suggestive music.

The calixtinian polyphony has been the object

of plenty of scholarly research, editions, revisions, and recordings.

Still, its transcription has always been extremely hard to interpret.

These difficulties derive from the fact that the notation used for this

polyphony was the one used for monodic chant in France at the time, so

that it does not convey any rhythmical value whatsoever. Thus, the

interrelation of the three voices in the Congaudeant, for instance,

turns extremely difficult.

This CD presents for the first time the full recording of the whole of the Calixtinus—both

monody and polyphony—. It follows the detailed and still valid

edition by Dom. Germán Prado, a monk in Silos: Liber Sancti Jacobi. Codex Calixtinus in two volumes, published in Santiago de Compostela in 1944.

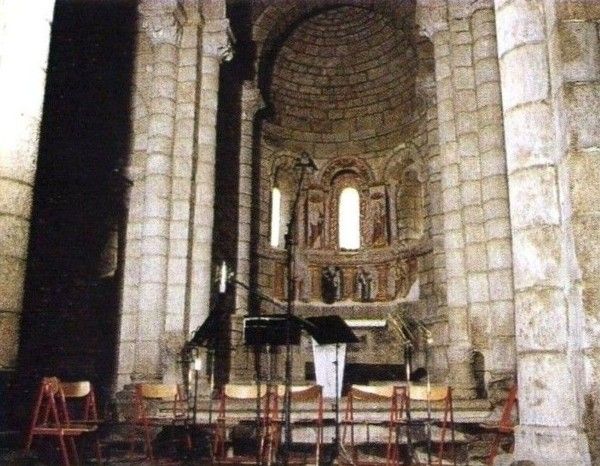

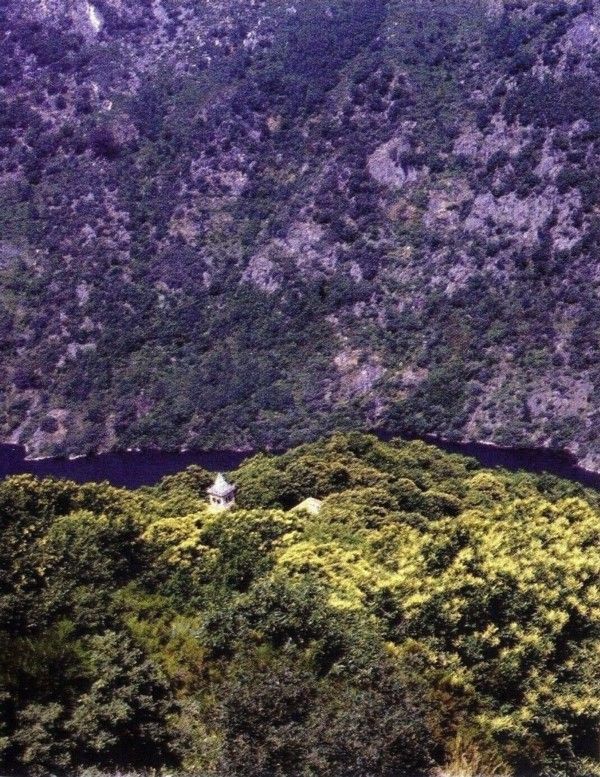

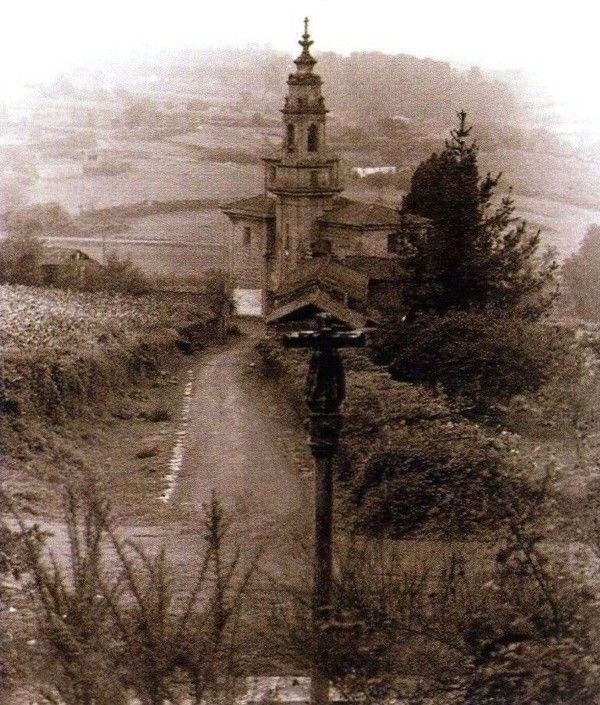

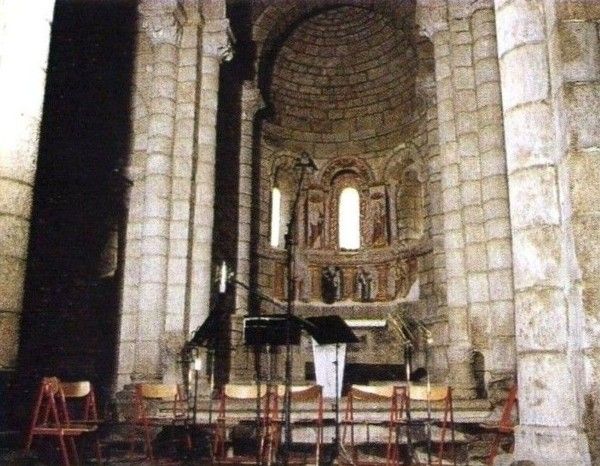

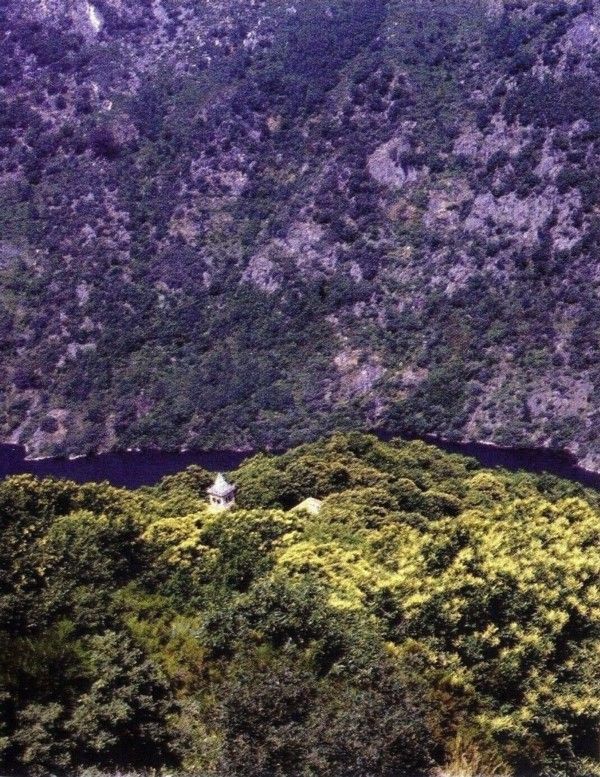

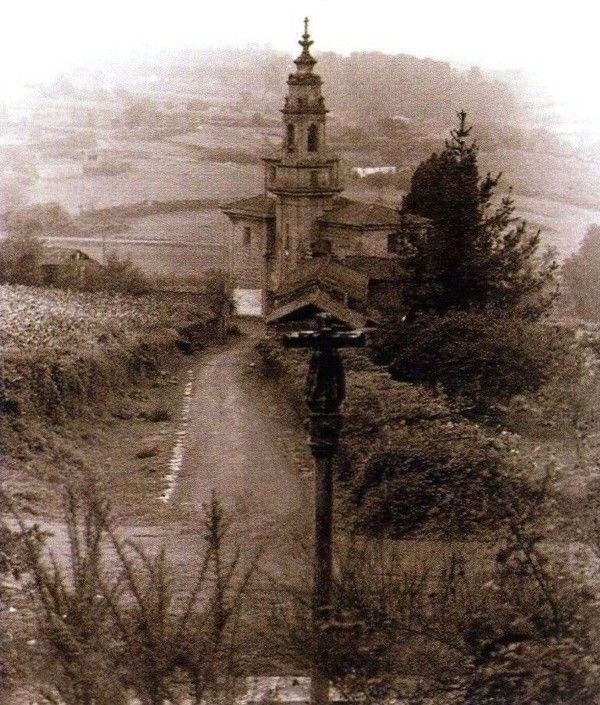

The

recording was carried out in a unique place which can represent any of

the monasteries in the Way of Santiago where these pieces could be

heard. This is the hidden monastery of Santa Cristina de Ribas de Sil,

known as “o Mosteiro” by the villagers, in the steep banks of the Sil

river that cuts across the “Ribeira Sacra”, one of the most wonderful

and withdrawn places in Galicia. As Father Yépez tells, the monastery

was founded in the 9th century, and it was completed in the 12th century

with the building of the church and the actual monastic premises.

Surely the vaults of this Cistercian monastery have provided the

adequate acoustics to this recording, so that this monument of western

culture that is the Codex Calixtinus has found the right place to

materialize in the magnificent interpretation by the Coro Ultreia from

Pontevedra.

RELIGIOUS POETRY IN THE CODEX CALIXTINUS

By Manuel C. Díaz y Díaz

As

far as religious poetry is concerned, the 12th century in Compostela

bears a proper name, the famous Codex Calixtinus, which has been kept in

the Cathedral of Santiago since then.

As

far as religious poetry is concerned, the 12th century in Compostela

bears a proper name, the famous Codex Calixtinus, which has been kept in

the Cathedral of Santiago since then.

The Codex Calixtinus, or rather the Liber Sancti Jacobi,

is a huge compilation of texts about St James which were put together

as an homage to the Apostle. Interesting both in its composition and in

its atmosphere, it comprises five books which contain liturgical pieces

on the matter of St James (Book I), St James's miracles (Book II), tales

about the bearing of St James's corpse (Book III), the history of

Charlemagne and his army's deeds in Spain, or Historia Turpini (Book

IV), and a guide to the Way of Santiago with a description of the city

of Santiago and its Cathedral (Book V). Initially, the two first books

(liturgy and miracles) made up one single independent work entitled

Jacobus. The present body bears the general title of Codex Calixtinus

because the compilation of its five books is atributed to pope Calixtus

II (1118-1125), although nowadays we do know that this attribution is

false.

The author of such a vast work wanted it placed under a

threefold patronage, taking care that the three patrons were in one way

or another linked to the manuscript, which is not the orginal manuscript

but a careful copy produced to be stored in the cathedral of Santiago.

The three patrons are: the presumed author of the whole volume, the Pope

of Rome Calixtus, who often marks many of the pieces in the Codex as of

his own doing; the Compostelan archbishop Diego Gelmírez, the most

likely sponsor of this as well as of many other Compostelan works; and

the patriarch William of Jerusalem, who will dealt with below. The

contribution of Cluny, the great Burgundian monastery, must also be

acknowledged; it stands as one of the great centers of diffusion of the

Santiago manuscript, which is paid homage for its role in the pilgrimage

to Santiago, and consequently in the splendor of the very Cathedral of

Santiago and its cult.

Since the Calixtinus still treats William

as patriarch of Jerusalem, it must have been compiled before 1147, for

it was in this year that he renounced his patriarchy. The Jacobus

must have been finished before 1140, when the great archbishop Gelmírez

is no longer recorded in history. Only after that could the rest of the

Calixtinus have been completed, and this by adding new pieces to the Jacobus

and by redoing and retouching some of the old material. In any case,

Calixtus's papacy appears only as a remembrance, something which many

Compostelans must have appreciated because he had been an extraordinary

promoter of the Santiago see.

The work was completely finished at

about 1160, and certainly before 1173, for it was then that the monk

from Monserrat Arnaldo de Monte undertook his precious copy of the book,

which he found an interesting novelty worthy of transcription.

Therefore, it is very likely that all the liturgical poems in the book

were produced at around 1130-1140.

The Codex Calixtinus as a

whole is repeatedly presented as a foreign product, intended for

foreigners, who must have been the most likely addressees of the work.

This intention, together with the already mentioned reference to Cluny,

made many scholars consider the Codex Calixtinus a French work, both in

what refers to its literary integrity and to its paleographic

realization. Certainly this is not so.

It can be said that every

ancient text dealing with St James the Apostle either comes from the

Codex Calixtinus exclusively or has it as its essential evidence.

Moreover, the Calixtinus stands as our only source of religious poetry

from the 12th century. We are left, therefore, alone with the Codex

Calixtinus. Texts and problems have it as their only critical referent.

Several

scholarly studies have dealt with Compostelan poetry: the illustrious

Jesuit Guido Maria Dreves compiled under the epigraph Carmina

Compostelana every piece from the Calixtinus into an appendix to Volume

XVII of the Analecta Hymnica Medii Aevi, dedicated to the Hymnodia lberica (Leipzig 1894). A new edition, already outdated in many ways, was produced by Peter Wagner in Friburg in 1931 when he studied Die Gesänge der Jacobusliturgie zu Santiago de Compostela aus dem sog. Codex Calixtinus

(“Liturgical Songs of Santiago de Compostela from the so-called Codex

Calixtinus”). Many of the poems had already been edited by Antonio López

Ferreiro in his Historia de la S.A.M. Iglesia de Santiago, II

(“History of the Church of Santiago”; Santiago 1889), in

which he closely follows F. Fita-A. Fernández Guerra, Recuerdos de un viaje a Santiago de Galicia

(“Recollections of a Trip to Santiago in Galicia”; Madrid

1880). All this works were bound to be outdone by the edition Liber Sancti Jacobi. Codex Calixtinus

(Santiago 1944), by the distinguished art historian Walter M.

Whitehill. For a number of reasons, this edition is as hard to come by

as the Codex itself. The meticulous skill of the Compostelan professor

Abelardo Moralejo produced a full translation of these texts with plenty

of notes in 1950 (reprinted in 1993 and 1998). A new edition of the

original Latin text has just been released by K. Herbers and A. Santos

Otero (Santiago, 1998). Fortunately, we are not unaided in this search.

The

compositions we are about to deal with are some 35, all different in

character and worth. They have been attributed to various authors

ranging from Pope Calixtus himself, of course, to Fulbertus of Chartres

or William of Jerusalem, and including an anonymous bishop from

Benevento or an unknown Galician doctor. Thus, we are presented with

pieces whose origin lies in places around the whole known world. On top

of this geographical dispersion, which points to some of the most

outstanding literary names of those times, we still have a poem

attributed to Pope Calixtus, which involves the three sacred languages

that were already on the inscription that Pilatus had wanted carved on

Christ's cross: Hebrew, Latin and Greek. That is to say, geographical

universality is conjoined by the more prestigious tradition derived from

true sacred universality.

Two from among the first compositions

in the Vigil for Santiago have been ascribed to Fulbertus of Chartres,

an excellent writer and poet who helped the Carnotian School grow into

high technical and lyrical standards. Three poems, presumably by William

of Jerusalem —one of the addressees of the Liber Sancti Jacobi—, can be

found in a feast within the octave of the great holy day of St James.

The three poems are highly achieved: the first one is written in

rhythmic iambic senarii, which are grouped in five-line verses with

bisyllabic rhyme; the second, more complex one is divided into

eight-line verses, of which ll. 1, 2, 3 and 5, 6, 7 have one single

tetrasyllabic trocaic word, while ll. 4 and 8 are heptasyllabic trocaic

feet with bisyllabic rhyme. The third one is presented as a short

version of the Passion of St James, to which it adds nothing; the poem,

however, was designed to be sung on any occasion (crebro cantanda) as

its easy rhythm and simple structure indicate, and it is full of poetic

resources such as its consonant rhyme, its distichs with two trocaic

dimeters, and the fact that each verse is followed by a chorus or

refrain with the invocation Iácobe iuua. Curiously enough, the consonant-rhyming syllabes are always those ending in - orum.

It is worth lingering over these two last poems. This is the first verse of the second poem mentioned:

locundetur

et letetur

augmentetur

fidelium concio;

solemnizet

modulizet

organizet

spirilati gaudio.

ie. in Moralejo's rhythmic version:

ie. in Moralejo's rhythmic version:

Numerous,

jubilant,

and joyous

of faithful this reunion;

rejoycing,

modulating,

and singing out

their emotion.

What

none of the versions reveal is the fact that the first tetrasyllabic

series increase proportionally, from the innermost realm of man to his

behaviour in the community; whereas the second series presents a new

variation in which singing (modulizet) and accompaniment (organizet) are

evoked. The first and second heptasyllables refer to the powerful will

that underlay the session: that the assembly, in accordance with the

early Christian ideal as cor unum et anima una, will rise spiritually in due praise to St James in his festivity.

Meeting

the most strict rules of the genre, the last poem is more popular in

tone, and this in spite of its many lexical resources —the only ones its

brevity allows for—.

Clemens seruulorum

gemitus tuorum

Iacobe iuua.

Flos apostolorum,

decus electorum

Iacobe iuua.

Gallecianorum

dux et Hispanorum

lacobe iuua.

Moralejo's translation reads:

To your poor people

who moan in piety,

give your aid St James.

Flower of Apostles,

honour of the chosen

give your aid St James.

Guide of the Galicians

and of the Spanish,

give your aid St James.

Notice

the subtle and precise succession of the various moments evoked by the

author, whose use of the Latin resources is masterful. Certainly the

author of these little jewels is of some account. The poems move swiftly

between its Latin erudition and the forms and rhythms the

romance-speaking people were beginning to appreciate.

As we have said, these poems have been attributed to William of Jerusalem. In his History of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (XIV 26), William of Tiro provides a valuable definition of our author: “uir simplex, modice litteratus”

(“a simple man with a mediocre education”). A handsome Flemish from

Malinas, William happened to make a good impression not only on on the

king, but also as on the VIP and common people of Jerusalem; if we take

de Tiro's remark into consideration, however, he does not appear as a

man particularly gifted for poetry, an art which demanded not only

inspiration, but also a profound knowledge of language and poetic

techniques. Thus, we are bound to presume that it was not him who

composed these works from the Codex even though they have long been

attributed to him. They are probably the work of some good poet or

other, Galician or maybe French, who chose to disguise himself behind

such a relevant pseudonym.

What can be said of the numerous works

attributed to Fulbertus of Chartres? Apart from four poems, they

comprise all the rich and varied pieces that make up the interesting

Farce Mass for St James. It deserves some of our attention due to its

fabulous performing character, in which there is a certain degree of

scenic interplay (with the altar as stage, of course). As its name

suggests, the missa farsa or Farce Mass is a service in which the main

pieces (Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, Agnus Dei and even a benediction)

are interspersed with various little excerpts, sometimes presenting two

choruses which reply each other's interventions as well as the main

singer's, who represents the officiant. This is best explained here by

reproducing the three first Kyries with a excerpt from the Sanctus:

The Kyrie reads as follows:

Rex inmense, pater pie, eleison

Kyrie eleison.

Palmo cuncta qui concludis eleison

Kyrie eleison

Soter theos athanatos eleison

Kyrie eleison

Notice

how the third piece is entirely made up of Greek words not entirely a

product of the artist's imagination, but rather taken from the famous

Byzantine trisagion preserved by the Roman liturgy.

After the first part of the Sanctus has been sung, the Hosanna in excelsis is presented thus:

Chorus: Hosanna, saluifica tuum plasma qui creasti potens omnia.

Singers: A

Chorus: tenet laus, honor decet et gloria, rex eterne in secula.

Singers: A

and on like this until the chorus completes the liturgical sentence singing in excelsis.

The

farce masses —which can take even more varied shapes, though never

richer as far as their literary achievement is concerned— become very

frequent around this time, especially in the most important churches in

France. To this extent was our Calixtinus up to date. But let us return

to Fulbertus of Chartres.

Fulbertus had been an excellent poet

(c. 1160) and a master to the renowned cathedral school of Chartres.

Many of his works, most of which are of great lyrical and literary

value, have survived. Our poems, however, do not appear among his

genuine production. This does not imply that we must consider them

apocryphal, but it is sound to presume that someone after Fulbertus

followed his trail and appropriated his name so as to bring his own

works to light.

We must still recall some other authors whose

name has not outgrown his connections to the Codex. Master Anselm uses

verses with three octosyllabic iambic lines, each one of which ends with

a chorus reading Fulget dies, transformed into Fulget dies ista

to close the verse. Whereas the chorus and its double form reveal the

popular hue of these pieces, their metric features are far from being

simple.

These works include some conducti, one of which has been

attributed to a Roman cardinal called Robertus (maybe referring to

Robert Pullen, archdeacon of Rochester and later cardinal, d. 1146);

another one to Fulbertus, and still a third one to the unnamed bishop

from Benevento mentioned above. Although we have much theory from the

12th and 13th centuries dealing with the conductus, its common form has

not been ascertained yet. Apparently its denomination—rather than its

metrics, which is very varied indeed—corresponds to the kind of lyrics

needed to be sung in certain tones, from which the so-called cantus

firmus was certainly excluded.

These works include some conducti, one of which has been

attributed to a Roman cardinal called Robertus (maybe referring to

Robert Pullen, archdeacon of Rochester and later cardinal, d. 1146);

another one to Fulbertus, and still a third one to the unnamed bishop

from Benevento mentioned above. Although we have much theory from the

12th and 13th centuries dealing with the conductus, its common form has

not been ascertained yet. Apparently its denomination—rather than its

metrics, which is very varied indeed—corresponds to the kind of lyrics

needed to be sung in certain tones, from which the so-called cantus

firmus was certainly excluded.

The collection of religious poetry

in various tones continues into the Appendix to the Calixtinus, a

compilation of pieces which were collected too late to be included in a

more adequate place within the Book of St James. Many names come up in

this section, although I am not so sure that their attribution does not

refer to the lyrics (some of which are very shallow), but rather to the

music, which is written for two and three voices sometimes, just like

some other instances in the very body of the Liber. This is the oldest

surviving compilation of this kind in Europe.

The analysis of one

of this pieces allows for a better assessment of the various

attributions, and posits one more methodogical procedure. It is a

conductus ascribed to Venantius Fortunatus, bishop of Poitiers and a

widely read poet of the 6th century who was highly esteemed, especially

in the Peninsula. Presumably, the piece was to be acted out, since a

note on the margin of the manuscript suggests that the refrain should be

sung by a child standing among the singers of the conductus. The piece

goes like this:

Salue festa dies, ueneranda pro omnia fies

qua celos subiit Iacobus, ut meruit

gaudeamus.

These are good elegiac distichs with the only addition of the refrain. It so happens that the distichs were taken from a cento compiling works by Fortunatus. Many other quotations from this poet were included in the sermons that can be found in the Liber Sancti Jacobi. This was probably done in many other cases, such as with the great Fulbertus of Chartres.

Centos

or simple evocations apart, we must nor forget that many of the pieces

in the Codex are a work of the compiler himself. Many of these pieces

are mere versifications of phrases and expressions already present in

other parts of the Liber, especially in sermons. Some of these sermons

were written by the compiler, some others surely were finished and

readied before he even began his task.

Many of the poems were

actually written by contemporary authors, even by Compostelan authors.

Given the many-fold origin and status of the pilgrims, this geographical

label is best understood not as a national or local concept, but rather

as referring to the constant pool of truly international people that

flooded Compostela in those times. No source informs about the coming of

literary personalities to Compostela; but we must not overlook the fact

that the two great works bestowed by Bishop Gelmírez on Compostela were

participated not only by Spaniards and Galicians, but also by

foreigners. Why should we not consider the same possibility for those

authors of religious poetry in the 12th century?

A good example

of this is the remarkable, easy-to-sing marching chant. These are

trocaic septenaries with bysillabic rhyme inspired in a well-known

classical meter. It has been attributed to Aymericus Picaud, presbyter

in Partenay near Vezelay, who appears also as donee of the Codex to the

Cathedral of Santiago. The present Compostelan Calixtinus has not been

preserved in whole, and it was completed thanks to some of the old

copies.The poem reads as follows:

A good example

of this is the remarkable, easy-to-sing marching chant. These are

trocaic septenaries with bysillabic rhyme inspired in a well-known

classical meter. It has been attributed to Aymericus Picaud, presbyter

in Partenay near Vezelay, who appears also as donee of the Codex to the

Cathedral of Santiago. The present Compostelan Calixtinus has not been

preserved in whole, and it was completed thanks to some of the old

copies.The poem reads as follows:

Ad honorem regis summi, qui condidit omnia

iubilantes veneremus Iacobi magnalia.

De quo gaudent celi ciues in superna curia

cuius facta gloriosa memnit ecclesia.

That is, in the often used translation by Moralejo:

In honour of the supreme king of it all,

let's praise St James's great deeds.

The heavenly curia rejoices at him,

and the Church remembers his glorious record.

Again,

this is a peculiar case for whose assessment we have quite a few

elements. It is quite likely that some character come from Vezelay to

Santiago wrote it to the honour and glory of the Apostle, and this in a

rhythmical metre that makes it easy to aprehend and apt to be sung.

Some of the pieces were extremely popular, such as the Dum paterfamilias,

whose music was composed outside of the Codex Calixtinus. This song has

become well-known as the “song of Ultreia”, due to its beautiful

refrain which was sung by pilgrims from the North or by Flemish pilgrims

as they marched on to Santiago. Presumably, it was the refrain that

gave way to the poem. In any case we find in it a perfect symbiosis of

the strictly popular quality of the refrain with the author's learned

Latin work.

When the good Father,

King of it all,

bestowed the twelve apostles

on his kingdoms,

did St James to his Spain

bring his saintly light.

The Latin for which is as follows:

Dum pater familias

rex uniuersorum

donaret prouincias

ius apostolorum,

lacobus Hispanias

lux illustrat morum.

We must not leave out the remarkable refrain I just referred to:

Herru Santiagu, grot Santiagu.

e ultr 'eia, e sus 'eia, Deus aia nos.

In

any case, Compostela appears as a thriving melting-pot of trends, forms

and novelties, both popular and learned. No wonder then that this rich

life, far from submitting to the straight and stiff liturgical pomp that

glittered in the Cathedral of Santiago, would in the end make an

impression on the people from Compostela and on the pilgrims, and would

give way to a constant and fruitful imitation.

THE CODEX CALIXTINUS, COMPOSTELAN LITURGICAL LANDMARK

Por Manuel Jesús Precedo Lafuente

Dean-President of the Most Excellent Cathedral Chapter of Santiago de Compostela

(Nov. 16, 1998)

The

12th century has bestowed two great works on the city of Santiago de

Compostela: one of them is an architectural and theological masterpiece,

Master Mateo's “Pórtico da Gloria” (‘Gates of Glory’); the other one is

the Codex Calixtinus, a work of most profound literary and musical

value. As we revive the musical matter from those times, which mark the

beginning of polyphony, it is but fair that we refer briefly to the

liturgical texts included in the Codex. The book has been attributed to

Pope Calixtus II, a relative to king Alfonso VII ‘the Emperor’, who was a

son of the Pope's brother, Don Raimundo, and of the famous Doña Urraca.

A Service to Compostela

The

moral author of the Codex is also presented as the actual author of its

liturgical texts. As he openly states, his endeavour is to provide the

Compostelan Church with enough material, carefully selected by him, to

keep the liturgical celebrations in honour of St James the Older from

resorting to texts which were already devoted to other Apostles. Buried

in the city to which he gave his name, the son of Zebedee surely

deserved to have his own devotional texts.

Scholars such as the

presbyter D. Elisardo Temperán Villaverde suspect that the literary

goods supplied by the Codex were actually never used in those times. The

fact that this collection of texts —which included readings,

benedictions, antiphons, prayers, responses for the dead, hymns,

homilies, as well as tales of the Apostle's passion and martyrdom— was

done without, however, does not go against its importance.

For

one thing, they let us know the solemnity with which the various

celebrations dedicated to St James took place. The Codex begins by

announcing the 12th century calendar of St James, which included three

festivities: two of them, the martyrdom and bearing of the Apostle's

remains, are still held nowadays; and the other one concerning St James

the Older's miracles, in which the Codex abounds, has faded out.

An Overwhelming Richness

The

matter of the texts, particularly of those by the Fathers of the

Church, and of the homilies is also worth mentioning. As for the former,

however, they are often hard to ascribe to any one author in

particular—whether this be Pope Calixtus himself or any other—and their

genuine attribution cannot be always determined for sure.

The

Calixtinus is not the first piece of religious literature about St

James. The first Jacobean hymn to be known in Hispanic liturgy came out

in the times of king Mauregato (d. in 789), even before the Apostle's

remains were found in 813-814. It is an acrostic writing which invokes

St James for protection for the mentioned monarch. The hymn calls the

Apostle “golden and refulgent head, defender and saint patron of Spain”,

titles which would be often repeated from then on because they express

the heavenly roles generally attributed to the Apostle who brought the

Gospels to the very end of the world and wanted to rest forever in this

most faraway corner.

Still, as we go deeper into the texts from

the Calixtinus, we ascertain praises to Christ's direct disciple and to

his link to Spain and Galicia. What follows has been taken from one of

the liturgical hyms: “People of Galicia, raise your new songs to Christ;

thank God for the coming of St James....under his guidance will the

flock graze on sacred pastures.” And Pope Calixtus begins like this one

of the sermons attributed to him: “With spiritual joy, let us rejoice in

this day, dearest brothers, for the most sublime apostle St James, son

of Zebedee, saint patron of Galicia.”

The Festivity of the Miracles

The Festivity of the Miracles

Since

the so-called “Festivity of St James's Miracles” is no longer a part of

the liturgical calendar, it seems appropriate to say a few words about

it here. The author of the Codex justifies the current dates for the

festivity. These are no doubt hypothetical, and to this day we cannot be

sure that these are the correct dates, since there is written evidence

in both cases. Only for the day of the martyrdom could we give an

approximate date, because Acts locates it in the Jewish Passover. The

Calixtinus marks March 25th following the Venerable Bede, to whom the

date would have been revealed in a vision by a friend of his. The

traditional date of July 25th was fixed by St Jerome, and December 30th

commemorates both the Bearing of the Apostle's remains and his election

as a disciple of Christ.

But the uniqueness of the Calixtinus

rests mainly on the Festivity of the Miracles. This is what Calixtus

says about the celebration: “It was St Anselm who piously commanded the

celebration of the Festivity of St James's Miracles, like the one about

the man who had killed himself and was brought back to life by the

Apostle, as well as all the other miracles he performed, and it is

usually held on October 3rd. And we confirm this fact herein.”

Twenty-two miracles are rendered in Book II of the Codex Calixtinus, and

some others are scattered in various other tales. But there is no doubt

that the Apostle's greatest miracle is his ever-growing cult and

adoration, the flourishing pilgrimage to the site of his sepulchre, and

the increasing number of pilgrims' conversions. That in itself would

suffice to celebrate its thaumaturgical function.

St James's Conches

It

is interesting to read about the vicissitudes underwent by the Codex

Calixtinus in Pope Calixtus II's lifetime, as told by the author

himself. Overcoming the harassment by thieves, the hazard of

imprisonment, shipwrecks, and even a fire, and rid of all his

possessions, he was finally able to preserve the book on which he had

worked since he was a child out of his devotion for St James. He would

finally bestow it on a Cluny monastery, so that its monks could judge

its orthodoxy and become the zealous custodians of what had been so hard

to keep away from many dangers and threats.

Calixtus ordered the

Codex to be written with the Cathedral of Santiago and the many

pilgrims in mind. Thus, he does not miss any chance to give all kinds of

advice to them. He deals with the various ways to enhance the piety of

those who head for Compostela, and he also provides practical advice for

an easy and pleasant journey. Nevertheless, he does not refrain from

warning them about the many tricks and swindles they may fall prey to,

like “the misdemeanors of the evil innkeepers who dwell in my Apostle's

way”. He is also aware of the interest in those mementos from Santiago

that the pilgrims are to take back home, such as the ones he calls “St

James's conches”. These are probably the “horns” from the Rías Bajas, as

the translators of the Spanish version believe. The author of the

Calixtinus ascribes magical powers to them: “it is told that whenever

the melody from a conch of St James, which every pilgrim always carries

with him, resounds in the ears of the people, these feel their faithful

devotion grow, and ward off their enemies' animosity, the rumble of

hail, the roughness of the storm ...”.

EUROPE'S FOUNDING SONG

Por Xosé Luis Barreiro Rivas

Universidade de Santiago de Compostela

On the map of Europe, the Way of Santiago

is like a sea-current flowing from the vast western plains of the Old

World, when the winds of change began to blow on the complex social,

economic and political structures of the Carolingian Empire. That is why

I often resort to E. M. Sait's metaphor in which he compares political institutions to coral reefs,1

for I have the impression that we inhabit a world resulted from the

random piling up of unnoticed material, dragged by currents of pilgrims,

traders, crusaders, intellectuals, warriors and onlookers who broke up

the rigid structures of the feudal society in the Early Middle Ages and

began building what is now, like a portentous coral reef, the fruitful

and immense reality of Europe.

Certainly, we now see pilgrimage

as a peculiar phenomenon that hardly fits our social life and our ways

of worship. But it represents the sheer dynamics of a hyerocratic

society, when social changes looked for their legitimacy to a religious

form that would enable the old codes to be challenged and replaced for

new sets of values.2 That is the reason why it is best to

look into the Jacobean phenomenon from two different perspectives:

firstly, as a religious instance whose occurrence brought about

important side-effects such as the progress in art, economy, culture and

the institutions; and secondly, as a political fact that fostered

social change and was staged around the worship of the Apostle.

Symbol

of a new cosmology created in Western Europe in the 9th and 10th

centuries, the Way of Santiago is the axis mundi of a Christendom which

emerged as the signs of political and social identity that had been

swept away by the barbarian invasions in the Early Middle Ages began to

amalgamate. As a cosmos-making device, the Way of Santiago defines the

values which mark the boundaries of Christianity, legitimize its sources

of authority, and generate the centralizing thrust which will organize

power in the emergent western kingdoms. Motivated both by their

religious faith and by the civil incentives in the great route to the

End of the World, the pilgrims placed their beliefs and their ideals

above the centrifugal forces that threatened to fragment and impair the

feudal society. This is how they became the officiants of universality,

the true holders and designers of a space which they themselves had

helped to build and structure.

Symbol

of a new cosmology created in Western Europe in the 9th and 10th

centuries, the Way of Santiago is the axis mundi of a Christendom which

emerged as the signs of political and social identity that had been

swept away by the barbarian invasions in the Early Middle Ages began to

amalgamate. As a cosmos-making device, the Way of Santiago defines the

values which mark the boundaries of Christianity, legitimize its sources

of authority, and generate the centralizing thrust which will organize

power in the emergent western kingdoms. Motivated both by their

religious faith and by the civil incentives in the great route to the

End of the World, the pilgrims placed their beliefs and their ideals

above the centrifugal forces that threatened to fragment and impair the

feudal society. This is how they became the officiants of universality,

the true holders and designers of a space which they themselves had

helped to build and structure.

The city of Santiago, western tip

of Christianity, grew as a result of all this and gradually became the

most important reference encouraging the birth of a new Europe. It

spread new values as its Way took in the artictic splendor and the

infrastructural efficiency necessary for a route on which hundreds of

thousands of pilgrims coming from all around the world were bound to

stage the coming of a new era. In order to unify the flow of

contributions stored by the current of pilgrims on the institutional

reefs of the Early Middle Ages, and in order to allow for the complex

construction of Europe, the Way of Santiago equipped itself with a new

theory of society. Conveyed by legends, myths, traditions, and oral

historical narratives, this theory completed the central idea of a

universal Christendom who journeyed from Eastern to Western Europe—or

from Jerusalem to Santiago—as its understanding of the world pivoted on

Rome.

If we take into account that in large part political

socialization is, at least originally, a non-political fact based on

educational, religious, and family relations,3 the founding

of Europe can be described as a process of political socialization

featuring the rising of a new affective and cognitive structure in the

political reality. This provoked an incipient institutionalization of

the centralizing powers—Church and Empire—which broke away from the

feudal immobility of the Early Middle Ages and gave way for social,

cultural and economic change.

The Carolingian Legend

belongs to these theoretical-doctrinal corpus. Resting on a masterful

epic-historical structure, it conveys the values which defined the

structure of authority and the social and political aims of the new

temporal and religious order born of Aix-la-Chapelle. Its best version

can be found in the so-called Historia Turpini, included in Book IV of the Codex Calixtinus.4

The

more undifferentiated and the less institutionalized a society is, the

more it depends on the indirect ways of socialization and on a formal

assimilation of the new political values to the preexistent, established

and largely internalized community values. Accordingly, as Stephen Driscoll

points out, the farther away a society is from the dominance of reading

and writing and from the means of documental spreading, the more

precise the language of symbols and the indirect expression of meaning

become. This is why we can say that, within the frame of a vast

world-making activity, the social and cultural importance of pilgrimage

must be linked to the socio-genesis of the European civilization. This

process steps ahead of the rising of the political structures of the

late Middle Ages and becomes the seminal substratum of the changes

undergone in the Renaissance.5

Every political system

rests on an organized subjective system of values that endows individual

actions with meaning, that legitimizes and disciplines the

institutions, and that gives a sense of stability to political decisions

articulated as parts of a long-range social construction.6

Thus, pilgrimage to Santiago can be considered a means of linking the

beliefs, psychology, and individual action of the medieval person to the

social aggregate; or as an instrument to create a political culture

which moved along two axes: from the individual to society, so as to

structure the norms and values that make the power organizations and

institutions cohere, and from society to the individual, so as to

provide him or her with means of social integration and clues to

political behaviour.

In its most basic version, pilgrimage has a

sacramental character. This character allows for an incomprehensible

spiritual idea to be felt and understood, which is why pilgrimage has

always been considered a hyerophany, ie. a form of the sacred that the

common person can experience directly. Besides the simple reality of the

tired man going after his sacred goal, however, there are other

components in pilgrimage that helped define its historical reality, and

determined its remarkable effects on the European society of the Middle

Ages. Along with the pilgrims came monastic life, the ritual and

doctrinal unification of the Church, the papal authority on the Catholic

Church, the underlying political identity of Christendom, new literary

forms, new social ways and usages, as well as techniques of production

and scientific developments, all of which unified European society,

raised its self-awareness, and stirred in it the feeling that it

inhabited its own dwelling, and owned its own world.7

If

history is the politics of the past, if it is the means to understand

the facts that underpin our world, then listening to the music from the Codex Calixtinus

is returning to the sounds that lay the foundations of Europe. Like

them, a whole aesthetics with a vast social hold spread around the

Christian world as a means of praying, and as the actual evidence that

the long pilgrimage routes never crossed the limits of the own,

not-to-be-declined cosmos. At the same time, when we ascertain the

tightness of the bond between today's individual and the melodic art of

some thousand years ago, we shiver at the picture of the abyss of time,

even though we do this from the comfortable security of having a “way of

the stars” that runs across the western sky, from Frisia to Fisterra,

in its search after the apostolic sepulchre in Santiago. It was here

where, at the end of the first millenium, the whole of Europe began its

long way back.

1 Sait, E.M. (1938): Political Institutions: A Preface. New York: D. Appleton-Century.

2 Cfr. Bellah, R. 1966. “Religious Aspects of Modernisation in Turkey and Japan”, in J.L. Finkle and R.W. Gable, eds. Political Development and Social Change. New York: Wiley.

3 Cfr. Dowse, R.E. and J.A. Hughes. 1972. Political Sociology. New York: Wiley. Spanish edition: 1990. Sociología Política. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. 5th. ed.

4 Book IV of the Codex Calixtinus comprises the Historia Turpini

(ff. 163 to 191 v.): “TTURPINUS DOMINI GRATIA ARCHIEPISCOPUS Remensis

ac sedulus...” Furthermore, numerous manuscripts (more than 250) from

the Historia Karoli Magni et Rotholandi include variants from the Calixtinus narrative: vid. C. Meredith-Jones's Historia Karoli et Rotholandi ou Cronique du Pseudo-Turpin: textes revus et publiés d'apres 49 manuscripts (These, Faculté des Lettres de l'Université de Paris, 1936).

5 Cfr. Elias, N. 1987. El proceso de la civilización. Investigaciones sociogenéticas y psicogenéticars. Madrid: F.C.E.

6 Cfr. Pye, L.W. and Verba, S. 1965. Political Culture and Political Development. Princeton NJ: Princeton UP.

7 As for contemporary political science, Ernst Cassirer vouched for the validity of myth as a way of shaping the great political instances of our time. Cfr. 1947. El mito del Estado. Mexico: F.C.E.

THE SOUND OF THE CODEX

It seems particularly difficult for a

person like myself to leave my natural environment, among wires and

microphones, and step from behind the shelter of the sound mixer in

order to explain how I dared participate in such a project. I have to

confess that, unlike the other people with whom I am honoured to share

some space in this book, I enjoy a very special advantage when it comes

to expressing my opinions on the Codex. For, who knows which was the

atmosphere that surrounded the interpretation of these works in medieval

times? Well, this was the first issue that struck me at the very start

of this project, and it also happens to be the doubt remaining at the

back of my mind once the task is finished.

It has become more and

more difficult in our world to come across virgin, unpolluted spaces.

It is hard to breathe this air because it is clogged with strange

substances; mass-media spread cultural pollution at the speed of light,

whether this be for the better of for the worse; the stars are not

visible to our eyes, not even in dark, open nights, due to the

artificial light shed by our cities; and some of us are particularly

worried about an animal in clear and present danger of becoming extinct,

even though it is never listed in National Geographic surveys: silence.

The first and most crucial technical problem that came up as we were

preparing the recording sessions was finding a place which offered the

acoustic conditions most adequate for the interpretation of the pieces

in the Codex, but which were sufficiently isolated from the ever present

noise granted daily by the civilization at the closing of the third

millennium. After trying out several locations, we finally found the

place. The church of the monastery of Santa Cristina de Ribas de Sil

displayed, together with a breathtaking landscape, the ideal conditions

to carry out our enterprise: a wonderful sonority due to its wooden

ceiling, the absolute availability of the premises thanks to the

generosity of the persons in charge of the monastery, and, above all,

the conditions of isolation and distance from populated areas necessary

to prevent non-natural sounds to sneak into the recording. But alas!,

there was no electric power. The very civilization from which we were

escaping gave us, in turn, the solution to this problem in the form of a

quiet fuel generator, prudently placed some hundreds of meters away,

which fed power to the light and recording units. We had but to wait for

the night to avoid the singing of birds and other unwanted sounds ...

except, of course, for bats and owls, who sometimes accompanied the Coro

Ultreia with their authoritative voices, as if wanting to assert that

they were there long before us, and that their music surely matches up

to ours.

Santa Cristina had a unique atmosphere for monody, as

far as both setting and sound were concerned, but the very first

attempts at polyphony and instruments revealed that the atmosphere was

rather too dense for them. That is why a location with a lower degree of

reverberation was preferred and the recording was moved to the

Santuario de Nosa Señora de Abades, a church in a very beautiful valley

near Santiago de Compostela. With its clean and transparent acoustics,

it adequately hosted and wrapped the voices of the Coro Ultreia, thus

allowing for a clearer recording of the various melodic lines.

The

third space, the Cathedral of Tui, was not chosen because of its

acoustic conditions as in the previous cases. Its sweet-fluted organ

provided the best enfolding for some of the pieces collected in the

Calixtinus, although we had to fight the background noise brought to us

by city life.

I will refrain from boring anyone with technical

details. Certainly technics was not the key to the sonority put into

this records. We have tried to avoid every unnecessary electronic

addition, and this is how we believe to have achieved the purest sound

possible for you, as it could be found in the wonderful places where we

spent many hours recording it. Just pour plenty of enthusiasm and

communication among the people participating in this project, and you

will have the recipe that has turned Fernando Olbés's dream into a

reality. For he was the one who transmitted it to everyone else

including me, who, like Fernando himself and insofar as I was involved

in it, would like to offer it to all who have gone before it came true

and and to all who have arrived in time to enjoy it.

Allow me to

finish off with a confession. I was lucky enough to listen to what I

think is the perfect sound for the Codex Calixtinus: I was, at three in

the morning and minus three degrees, buried in the dark, standing at the

doorstep of a romanesque church from the XII century lost in the Sil

canyon, feeling the silence only broken by the sound of the slightest

rain and the voices of some twenty madmen singing musical works eight

hundred years old. Not many people have had such a chance. . not even

the madmen “themselves”.

Pablo Barreiro Rivas. Sound technician.

IACOBUS

IACOBUS The Calixtinus—so called because most of the

pieces in it were attributed to Pope Calixtus II— was compiled at the

start of the last third of the 12th century (probably in 1160 to 1170)

with materials of varied origin and authorship. Dr. Lopez Calo asserts

that the materials in the Calixtinus were written before they were ever

included in the Codex, though immediately before, “so that only a few

years could have passed between the writing and compilation of these

materials and their inclusion in this and other extant copies of the

Liber Sancti Iacobi. It can be ascertained that the idea of compiling

these writings in honour of St James the Apostle came about in the time

of bishop Diego Gelmírez, more exactly from c. 1120 on. This means that

the Codex was but one more of the many endeavours conceived and

undertaken by the great Compostelan prelate in order to exalt his church

and to present an audience as large as possible with the excellence of

the Apostle, of his worship and of the city that held its remains”. Calo

continues: “although the text was the work of several copyists, most of

it was carried out by one single scribe who worked under heavy French

influence, probably Cluniac”. Indeed, Gelmírez brought in the most

outstanding representatives of culture at the time, Cluny monks, for he

believed this would raise the cultural level in Santiago. That is why

most of the writing and musical notation of the Codex are French, more

precisely Northern French.

The Calixtinus—so called because most of the

pieces in it were attributed to Pope Calixtus II— was compiled at the

start of the last third of the 12th century (probably in 1160 to 1170)

with materials of varied origin and authorship. Dr. Lopez Calo asserts

that the materials in the Calixtinus were written before they were ever

included in the Codex, though immediately before, “so that only a few

years could have passed between the writing and compilation of these

materials and their inclusion in this and other extant copies of the

Liber Sancti Iacobi. It can be ascertained that the idea of compiling

these writings in honour of St James the Apostle came about in the time

of bishop Diego Gelmírez, more exactly from c. 1120 on. This means that

the Codex was but one more of the many endeavours conceived and

undertaken by the great Compostelan prelate in order to exalt his church

and to present an audience as large as possible with the excellence of

the Apostle, of his worship and of the city that held its remains”. Calo

continues: “although the text was the work of several copyists, most of

it was carried out by one single scribe who worked under heavy French

influence, probably Cluniac”. Indeed, Gelmírez brought in the most

outstanding representatives of culture at the time, Cluny monks, for he

believed this would raise the cultural level in Santiago. That is why

most of the writing and musical notation of the Codex are French, more

precisely Northern French. As

far as religious poetry is concerned, the 12th century in Compostela

bears a proper name, the famous Codex Calixtinus, which has been kept in

the Cathedral of Santiago since then.

As

far as religious poetry is concerned, the 12th century in Compostela

bears a proper name, the famous Codex Calixtinus, which has been kept in

the Cathedral of Santiago since then. ie. in Moralejo's rhythmic version:

ie. in Moralejo's rhythmic version: These works include some conducti, one of which has been

attributed to a Roman cardinal called Robertus (maybe referring to

Robert Pullen, archdeacon of Rochester and later cardinal, d. 1146);

another one to Fulbertus, and still a third one to the unnamed bishop

from Benevento mentioned above. Although we have much theory from the

12th and 13th centuries dealing with the conductus, its common form has

not been ascertained yet. Apparently its denomination—rather than its

metrics, which is very varied indeed—corresponds to the kind of lyrics

needed to be sung in certain tones, from which the so-called cantus

firmus was certainly excluded.

These works include some conducti, one of which has been

attributed to a Roman cardinal called Robertus (maybe referring to

Robert Pullen, archdeacon of Rochester and later cardinal, d. 1146);

another one to Fulbertus, and still a third one to the unnamed bishop

from Benevento mentioned above. Although we have much theory from the

12th and 13th centuries dealing with the conductus, its common form has

not been ascertained yet. Apparently its denomination—rather than its

metrics, which is very varied indeed—corresponds to the kind of lyrics

needed to be sung in certain tones, from which the so-called cantus

firmus was certainly excluded. A good example

of this is the remarkable, easy-to-sing marching chant. These are

trocaic septenaries with bysillabic rhyme inspired in a well-known

classical meter. It has been attributed to Aymericus Picaud, presbyter

in Partenay near Vezelay, who appears also as donee of the Codex to the

Cathedral of Santiago. The present Compostelan Calixtinus has not been

preserved in whole, and it was completed thanks to some of the old

copies.The poem reads as follows:

A good example

of this is the remarkable, easy-to-sing marching chant. These are

trocaic septenaries with bysillabic rhyme inspired in a well-known

classical meter. It has been attributed to Aymericus Picaud, presbyter

in Partenay near Vezelay, who appears also as donee of the Codex to the

Cathedral of Santiago. The present Compostelan Calixtinus has not been

preserved in whole, and it was completed thanks to some of the old

copies.The poem reads as follows:

The Festivity of the Miracles

The Festivity of the Miracles Symbol

of a new cosmology created in Western Europe in the 9th and 10th

centuries, the Way of Santiago is the axis mundi of a Christendom which

emerged as the signs of political and social identity that had been

swept away by the barbarian invasions in the Early Middle Ages began to

amalgamate. As a cosmos-making device, the Way of Santiago defines the

values which mark the boundaries of Christianity, legitimize its sources

of authority, and generate the centralizing thrust which will organize

power in the emergent western kingdoms. Motivated both by their

religious faith and by the civil incentives in the great route to the

End of the World, the pilgrims placed their beliefs and their ideals

above the centrifugal forces that threatened to fragment and impair the

feudal society. This is how they became the officiants of universality,

the true holders and designers of a space which they themselves had

helped to build and structure.

Symbol

of a new cosmology created in Western Europe in the 9th and 10th

centuries, the Way of Santiago is the axis mundi of a Christendom which

emerged as the signs of political and social identity that had been

swept away by the barbarian invasions in the Early Middle Ages began to

amalgamate. As a cosmos-making device, the Way of Santiago defines the

values which mark the boundaries of Christianity, legitimize its sources

of authority, and generate the centralizing thrust which will organize

power in the emergent western kingdoms. Motivated both by their

religious faith and by the civil incentives in the great route to the

End of the World, the pilgrims placed their beliefs and their ideals

above the centrifugal forces that threatened to fragment and impair the

feudal society. This is how they became the officiants of universality,

the true holders and designers of a space which they themselves had

helped to build and structure.