medieval.org

amazon.com

Naxos 8.557340

2005

medieval.org

amazon.com

Naxos 8.557340

2005

From plainchant via simple 9th-century harmonies and the virtuosic

duets of Master Léonin (known as organum), this hauntingly

beautiful sequence charts the birth of polyphony up to the first music

in four independent parts – composed by Master Pérotin and

sung during the liturgy at the new Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris.

From the official laying of the cornerstone in 1163 to the completion

of the famous Western façade almost a hundred years later,

Notre-Dame was the fertile home of singers and composers whose

extraordinary handiwork has come down to us in the magnus liber organi:

the “Great Book of Organum”.

1. Beata viscera [6:09]

monophonic conductus · PÉROTIN —

soprano Rebecca Hickey

2. Viderunt omnes [2:22]

plainchant — MEN, FULL

Viderunt omnes [17:35]

2-part organum · LÉONIN?

[tenor R. Eteson + tenors A. Hickey, T. Watson, bass F. Brett]

3.

Viderunt omnes ... · 2-part organum [2:09]

4.

... fines terre salutare dei nostri jubilate deo omnis terra · plainchant [0:54]

5.

Notum fecit ... · 2-part organum [0:45]

6. ... Dominus ... · 2-part organum [1:35]

7. ... salutare suum ante conspectum gentium revelavit ... · 2-part organum [3:44]

8.

... justitiam suam · plainchant [0:24]

[soprano J. Forbes + soprano R. Hickey, alto K. Oswald, countertenor A. L'Estrange]

9.

Viderunt omnes ... · 2-part organum [1:20]

10.

... fines terre salutare dei nostri jubilate deo omnis terra · plainchant [0:53]

11.

Notum fecit ... · 2-part organum [0:49]

12. ... Dominus ... · 2-part organum [0:56]

13. ... salutare suum ante conspectum gentium revelavit ... · 2-part organum

[2:08]

14.

... justitiam suam · plainchant [0:23]

[UPPER & LOWER CHOIRS]

15.

Viderunt omnes ... · 2-part organum [0:38]

16.

... fines terre salutare dei nostri jubilate deo omnis terra · plainchant [0:58]

... Dominus... • Factum est salutare / ... Dominus ... [4:47]

2-part clausulae ... Dominus ...

17. I [0:56] LOWER CHOIR

18. II [0:54] UPPER CHOIR

19. III [0:59] LOWER CHOIR

20. IV [0:38] UPPER CHOIR

21. V [0:39] LOWER CHOIR

2-part motet

22. Factum est salutare / ... Dominus .... [0:40] soprano J. Forbes, UPPER CHOIR

Viderunt omnes [16:01]

4-part organum • PÉROTIN

[soprano R. Hickey, tenor A. Hickey, bass F. Brett + tenor T.Watson/countertenor A. L'Estrange/A. Pitts]

23.

Viderunt omnes ... · 4-part organum [5:15]

24.

... fines terre salutare dei nostri jubilate deo omnis terra · plainchant [0:56]

25.

Notum fecit ... · 4-part organum [3:55]

26. ... Dominus ... · 4-part organum [0:47]

27. ... salutare suum ante conspectum gentium revelavit ... · 2-part organum

[3:38]

28.

... justitiam suam · plainchant [0:24]

29. Viderunt omnes fines terre salutare dei nostri jubilate deo omnis

terra · plainchant [1:12] FULL

30. Non nobis Domine [7:10]

organum examples (Psalm 115/113b) after 9th-century Scolica [Scholia] enchiriadis — FULL

31. Sederunt principes [13:31]

4-part organum / plainchant • PÉROTIN

[sopranos J. Forbes, R. Hickey, alto K. Oswald + countertenor L'Estrange/A. Pitts]

32. Vetus abit littera [2:29]

4-part conductus — FULL

Tonus Peregrinus

Antony Pitts

Joanna Forbes, Rebecca Hickey — sopranos

Kathryn Oswald — alto

Alexander L’Estrange — countertenor

Richard Eteson, Alexander Hickey, Timothy Watson — tenors

Francis Brett — bass

TONUS PEREGRINUS

TONUS PEREGRINUS is a group of

individual musicians each forging their own diverse careers, yet unified

when they meet to make music from many times and places. The ensemble

was founded by the composer and producer Antony Pitts in 1990, while

studying at New College, Oxford under Dr Edward Higginbottom. The Latin

term tonus peregrinus was the name given to one of the Church’s

ancient psalm tones; in turn, this chant was based on a Jewish melody

which may have been sung by Jesus and the disciples at the Last Supper.

This particular psalm tone was unusual in that it had a different

recitation tone in each half, hence its name, ‘wandering tone’; it was

also known, despite its history, as the tonus novissimus, or

the ‘newest tone’. TONUS PEREGRINUS combines these two characteristics

in a repertoire that ranges far and wide from the end of the Dark Ages

to scores fresh from the printer, and with an interpretative approach

that is both authentic and original. It was a recording of Pitts’s

sacred choral music, Seven Letters

(now on Hyperion CDA67507) that led Klaus Heymann to commission the

ensemble’s first two recordings for Naxos: Arvo Pärt’s

Passio (Naxos 8.555860), which hit the top of the BBC Music Magazine chart and won a Cannes Classical Award, and a pairing of the earliest complete polyphonic Mass and Passion settings The Mass of Tournai (Naxos 8.555861). Forthcoming releases include Sweet Harmony, Masses & motets by John Dunstable (Naxos 8.557341), the first-ever opera Le Jeu de Robin et Marion by Adam de la Halle (Naxos 8.557337), and Hymnes and Songs of the Church (Naxos 8.557681). The Naxos Book of Carols

is available both as a CD (Naxos 8.557330) and as a book published

jointly with Faber Music. The ensemble’s website is at: www.tonusperegrinus.co.uk; for a free e-newsletter, please email: news@tonusperegrinus.co.uk.

Joanna Forbes

Joanna

Forbes studied cello and piano from an early age and read Music at

Hertford College, Oxford. Best-known for her work with world-renowned a

cappella group the swingle singers, of which she was

soprano/Musical Director for over six years, she enjoys a varied career

as a classical soprano, both as a soloist and in consorts, jazz singer,

arranger, lyricist, CD producer, workshop leader and singing teacher.

Rebecca Hickey

Rebecca

Hickey has sung in choirs from a very early age. She started her formal

singing studies whilst at university in York and now sings in a number

of small choirs and vocal ensembles.

Kathryn Oswald

Kathryn

Oswald read Music at Worcester College, Oxford, where she held a Music

Scholarship. She now pursues a busy and varied musical career,

performing regularly with other leading choirs and ensembles, and also

as a solo recitalist. She features as a voice-over artist for BBC Radio 3

and Unknown Public Radio, and is editorial director at Faber Music.

Alexander L’Estrange

Alexander

L’Estrange was a chorister at New College, Oxford and later read Music

at Merton College, singing in the choir of Magdalen College and

graduating in 1994 with First Class Honours. Besides singing

countertenor professionally, he is also much in demand as a composer,

arranger and jazz double bass player.

Richard Eteson

Richard

Eteson has been singing all his life. From an early age he was a

chorister at King’s College, Cambridge, and later a choral scholar

there. He has since sung tenor in many of London’s finest choirs and

vocal ensembles whilst being in demand up and down the country as an

oratorio soloist.

Alexander Hickey

Alexander

Hickey started singing as a chorister in Hereford Cathedral, went up to

Christ Church, Oxford, as a choral scholar and now practises as a

barrister. He regularly sings with renowned amateur and professional

choirs in and around London.

Francis Brett

Francis

Brett was a choral scholar at King’s College, Cambridge where he read

Music. He studied as a postgraduate at the Royal College of Music and

has since performed a wide variety of music including opera at Covent

Garden and many of the major works of oratorio.

Timothy Watson

Timothy

Watson studied history and French at Oxford, completing a doctorate on

the French Renaissance, and lectured at the Universities of Oxford and

Newcastle. A former principal percussionist of the National Youth

Orchestra, he studied at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique

de Lyon with François Dupin, and performed for the first time with

Tonus Peregrinus in 1990, playing vibraphone in the première of Music for a Large Audience.

He has also sung with the choirs of Magdalen and Christ Church Oxford,

Schola Cantorum of Oxford, and the Opéra de Lyon. In 2002 he left

British academe for the religious life, and is currently a member of the

Chemin Neuf Community in south-east France.

Antony Pitts

Antony

Pitts was born in 1969 and sang as a boy in the Chapel Royal, Hampton

Court Palace. He was an Academic Scholar and later Honorary Senior

Scholar at New College, Oxford and graduated in 1990 with First Class

Honours. While at New College he founded TONUS PEREGRINUS and in 2004

won a Cannes Classical Award for his interpretation of Arvo Pärt’s Passio

with the ensemble. He joined the BBC in 1992, and worked for many years

as a Senior Producer for BBC Radio 3, winning the Radio Academy BT

Award for Facing the Radio (1995) and the Prix Italia for A Pebble in the Pond in 2004. For the turn of the Millennium he devised an eighteen-hour history of Western music called The Unfinished Symphony, and more recently harmonized all four Gospel accounts of the Passion in A Passion 4 Radio.

He began composing at an early age and has written pieces for Cambridge

Voices, the Clerks’ Group, European Chamber Opera, the London Festival

of Contemporary Church Music, Oxford Camerata, the Oxford Festival of

Contemporary Music, Rundfunkchor Berlin, Schola Cantorum of Oxford, the

Swingle

Singers, and the Choir of Westminster Cathedral. Faber Music publish some of his scores, including the forty-voice motet XL, and Hyperion have recently released a CD of his sacred choral music called Seven Letters (CDA67507). He also teaches at the Royal Academy of Music.

Recorded at Chancelade Abbey, Dordogne, France, from 5th to 9th January, 2004

Producer: Jeremy Summerly • Engineer: Geoff Miles • Editor: Antony Pitts

Performing editions and booklet notes: Antony Pitts

Recorded and edited at 24-bit resolution

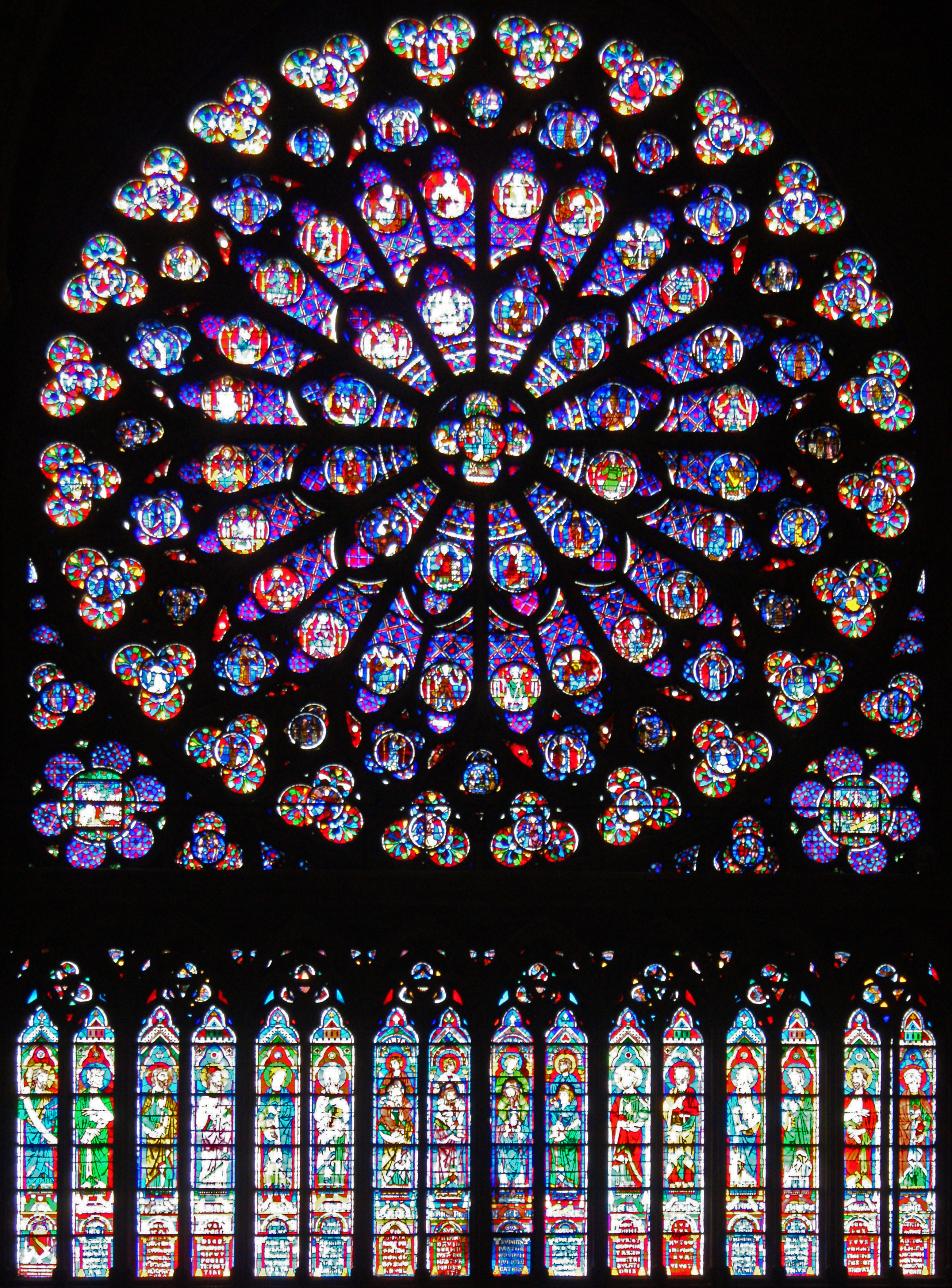

Cover Picture: The south transept rose window at Notre-Dame by Maria Jonckheere

(by kind permission)

℗ & © 2005 Naxos Rights International Ltd.

The cornerstone of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris was laid in 1163; by

c.1250 its imposing Western façade had been completed. During

this period the vast body of polyphonic music known as the magnus

liber organi was composed, compiled and edited – capped at

the turn of the 12th century by Magister Pérotin’s

celebrated organum Viderunt omnes, one of the very first pieces

written in four independent parts. Pérotin and his generation

were building on the legacy of another “master”,

Léonin: the extra 2-part versions of "Dominus" were designed to

replace the sections of Léonin’s original organum. The

foundations of polyphony and the Notre-Dame style are found in the

simple organum of a 9th-century treatise. Underneath it all, and

supporting a thousand years of Western musical history, is plainchant

– the ancient melody of the Church.

Viderunt omnes... “All the ends of the earth have seen the

salvation of our God” – this great Old Testament vision

aptly sums up the inspiration for both the architecture of Notre-Dame

in Paris and the liquid equivalent to be found in the Cathedral’s

magnus liber organi – “the great book of

organum”.

A picture postcard of Notre-Dame Cathedral tells you something of its

form and appearance but little of its detail and none of its power:

even the best efforts of imagination are not enough to appreciate fully

its immensity until you are right there, standing next to what John

Julius Norwich neatly summarised as the “first cathedral built on

a truly monumental scale”. Likewise the music written for the

cathedral needs to be heard as near to lifesize volume as feasible to

understand its intensity and force.

Visitors to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame are first of all struck by the

imposing Western façade, but on entering the building the

experience is transformed by what Abbot Suger of St Denis – one

of the forefathers of the Gothic style of architecture – had

conceived as “the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most

sacred windows pervading the interior beauty”; then there is the

awareness of a vast mass of people contained within the towering walls

and arches; and above all, the unmistakeable sound of distant voices

and movement reflected from innumerable ancient corners. For the

Parisian musicians and worshippers living in the late 12th and early

13th Centuries, however, this was a dynamic experience as the new

structure slowly took shape above the city skyline: a building project

that would span several generations from the laying of the cornerstone

in 1163.

Léonin, who was considered the master of polyphonic composition

in his time and who appears to have been responsible for the magnus

liber in its original form, must have spent much of his career in

the unfinished ‘choir’ or Eastern portion of the Cathedral,

separated from the regular sounds of construction by some kind of

temporary screen which perhaps was moved column by column westwards

over the years. By the time Pérotin made a new edition of

Léonin’s magnus liber and added his own massive

polyphonic versions of two Gradual chants – most likely for

feast-days in 1198 and 1199 – practically the entire space of the

Cathedral was ready to resonate in sympathy. Over the next half-century

and beyond work continued on the building until it was as complete as

it ever would be.

Certainly that is the story that seems to be corroborated by the

enormous body of music in the magnus liber itself. The

foundation of this repertoire is plainchant – unmeasured melodies

associated with every liturgical moment in the Church’s calendar.

Viderunt omnes (track 2) is a chant for Christmas Day and its

octave, the Feast of Circumcision.

There are two very simple ways of constructing polyphony out of

plainchant: either by adding a drone – one note held on as a

pedal under the plainchant, or by simultaneously singing the same

plainchant at a fixed interval above or below (the most obvious example

is of men and women, or men and boys singing the same tune an octave

apart). The 9th-century treatise Scolica [or Scholia] enchiriadis

demonstrates this spontaneous and unwritten practice of parallel

organum with a number of examples which we have recorded here as

individual verses of a psalm (track 30).

On top of these early edifices in Western polyphony we can imagine ad

hoc experiments in the performance of plainchant in a measured style

(with each note either the same length or twice as long as the next),

and in the improvisation of a free part over the existing plainchant.

Today it is easy to forget how well these tunes, especially those for

feast-days such as Christmas or Easter, would have been known by both

the professionals in the choir and the congregation in the nave.

The two-part music or organum duplum from Notre-Dame most

commonly associated with Léonin (tracks 3-16) is built upon all

these earlier developments, with the familiar tune of the plainchant

either slowed down while a second part elaborates a clearly soloistic

line (organum purum), or rhythmicised into the same

‘modal’ system as the new solo line (discantus). The

rules for unravelling 13th-century notation are relatively unambiguous

for discantus or discant style, but they leave us with plenty

of rhythmic options for the longer, more virtuosic sections of organum

purum – on this recording we have explored a number of the

many solutions (compare tracks 3 and 9).

It was the more regular discantus sections which proved most

memorable and consequently attracted the attention of up-and-coming

composers, including Pérotin. One section from the Viderunt

omnes in particular – with the single, crucial word

“Dominus” (tracks 6 and 12) became favourite fabric for

rhythmic and harmonic experimentation, and many new two-part versions

of this section were composed (including tracks 17-21), either to be

inserted as substitute clausulae or possibly as free-standing

pieces. In the furnishing of new words to the upper part in Factum

est salutare / Dominus (track 22) there are the audible seeds of

the motet – which was to become a separate musical structure with

a future far outside its original liturgical setting.

With the addition of a third, and then a fourth voice, the rhythmic

organisation of the discant style of organum was fully extended to the

upper parts throughout – just as the Cathedral’s original

arcade, gallery, triforium, and clerestory had to be carefully

co-ordinated. And just as the exceptional height of the Gothic style of

architecture required new solutions to the problems of this scale of

weight-bearing, there were also further harmonic implications of

combining so many voices – composers had to discover how to

balance intricate mixtures of consonance and dissonance (harmonic

intervals which sound relatively more or less pleasing to the ear) over

a long span of time. According to an Englishman visiting Paris in the

later 13th Century (the posthumously-labelled ‘Anonymous

4’) it was “Master Pérotin who made the best quadrupla”,

and it is these earliest surviving examples of four-part harmony which

open the manuscript Florence, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, plut.

29.1 (‘F’) from which the editions for this recording were

largely made.

Our approach on this recording has been to combine what we know of

12th- and 13th-century notational theory with the practical results of

our own encounter with this celebrated style; above all, we have aimed

to adopt a pace and an intensity to match the scale of the building for

which this music was written. If, as for today’s visitors to

Notre-Dame or for the scribe of the manuscript known as

‘F’, it is size that creates the best initial impression,

then go straight to Pérotin’s Viderunt omnes

(tracks 23-28) or Sederunt principes (track 31) – written

for the day after Christmas when St Stephen the first Christian martyr

(and co-patron of the Cathedral) was remembered. If, however, time

allows listening all the way through from Pérotin’s

freely-composed melody Beata viscera (track 1) to a four-part

conductus Vetus abit littera (track 32), then hopefully we will

have conveyed something of the staggering cumulative effect of a Gothic

cathedral-in-progress.