Gardens of Delight

/ The Telling

Roses, Lilies & Other Flowers in Medieval Song

medieval.org

amazon.co.uk

spectable.com

Prodiges

2016

[64:58]

SPAIN

1. La rosa enflorese [3:57]

ANON. (15th century) | traditional Sephardic song

CN, AP, LS

2. Pues que tu reyna del cielo [3:03]

ANON. (late 15th century) | text by Juan del Encina (1468–1529/1530)

Cancionero de Palacio, Madrid, Biblioteca Real, MS 1335, fol. 246v

CN, AP, LS

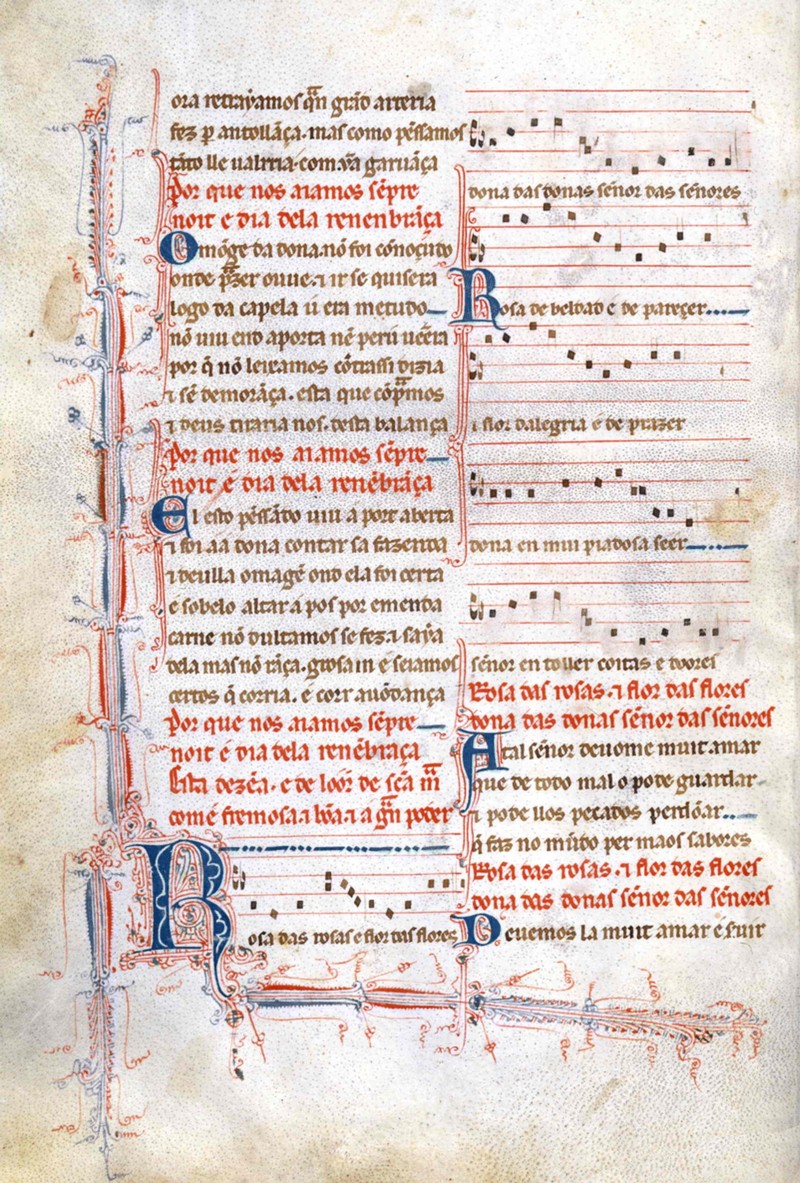

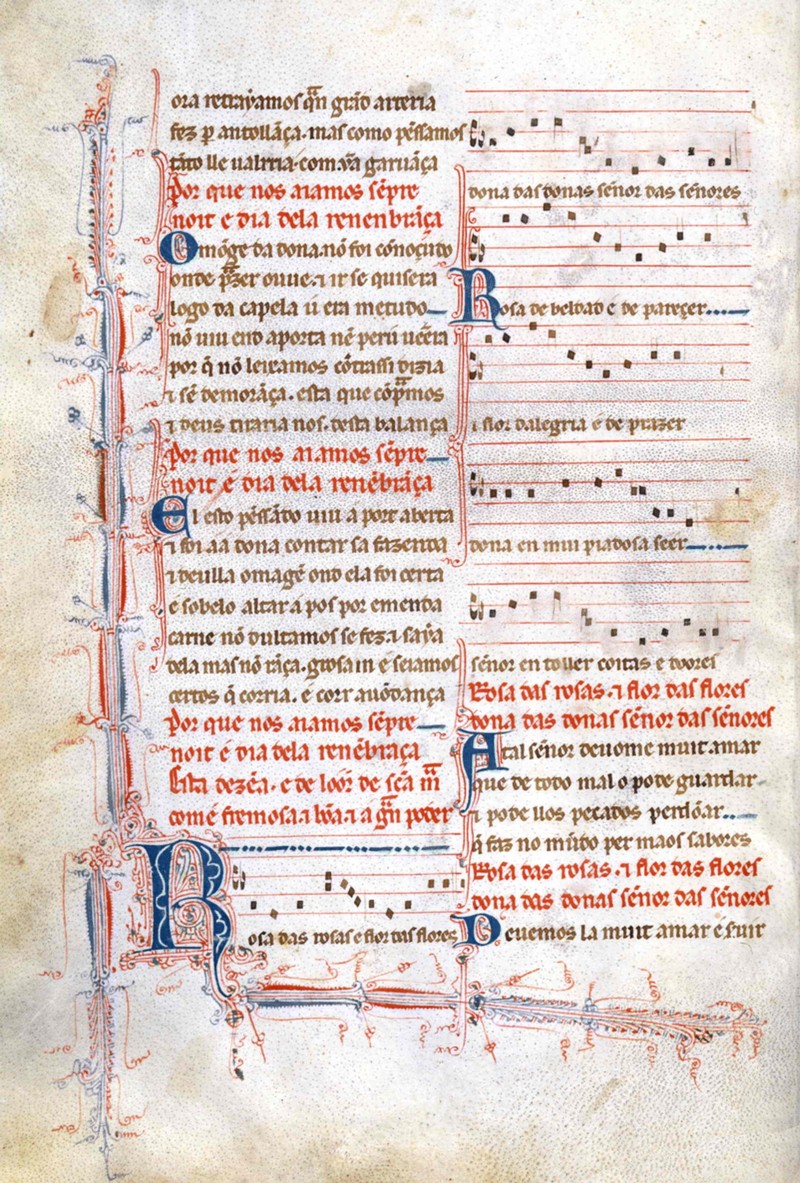

3. Rosa das rosas [3:45]

CSM 10

ANON. (13th century) | Cantiga No. 10 from Cantigas de Santa Maria

CN, AP

FRANCE

4. De tout flors [4:10]

15th century intabulation of a song by Guillaume de MACHAUT (1300–1377)

Faenza Codex, fol. 37v–38v

LS

5. Plus bele que flor~Quant revient et fuelle et flor~L’autrier joer m’en alai~Flos [2:52]

ANON. (13th century) | Montpellier Codex, fol. 26v–28v

CN, AP, LS

6. O virgo pia~Lis ne glai~Amat [3:06]

ANON. (13th century) | Montpellier Codex, fol. 227v–228v

CN, AP, LS

ENGLAND

7. Ther is no rose of swych virtu [4:41]

ANON. (c.1420) | Trinity Carol Roll, MS. O.3.58

CN, AP, LS

8. Ad rose titulum [3:41]

ANON. (14th century) | Cambridge Gonville & Caius MS 512/543, fol. 260v

LS

ITALY

9. O rosa bella, o dolce anima mia [9:07]

Johannes CICONIA (1370–1412) |

Text based on a poem by Leonardo Giustiniani (1385–1446)

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, nouvelles acquisitions

françaises, MS 4379, fol. 46v–48r

CN, AP, LS

10. Laude novella sia cantata [4:26]

ANON. (13th century) | Laudario di Cortona, fol. 3v–5v

CN, AP, LS

11. Un fiore gentil m’apparse [3:36]

Antonio ZACARA DA TERAMO (c.1350–c.1415) | Lucca Codex, fol. 17

CN, AP, LS

GERMANY

12. Der winter will hin weichen [3:21] ANON. (15th century)

Lochamer Liederbuch, pp.6–7

AP, LS

13. Unter den Linden [3:43]

ANON. (c.12th-13th century) | trouvère melody ‘En mai au douz tens novels’

text by Walther von der Vogelweide (c.1170–c.1230)

CN, LS

14. Ave generosa [7:16]

Hildegard of BINGEN (1098–1179) | text by Hildegard of Bingen

Riesencodex, fol. 474v

15. Procession from Ordo Virtutum [5:15]

text by Hildegard of Bingen

(Riesencodex, fol. 481v)

CN, LS

The Telling

Clare Noburn — voice

Ariane Prüssner — voice

Leah Stuttard — medieval harp, frame drum, voice

Original anonymous texts unless stated otherwise

Translations © 2018 Clare Norburn

Supplemental research: Leah Stuttard

Recorded at St Mary Magdalene, Sherborne, UK, 10–12 January 2018

Produced and engineered by Adrian Hunter

24bit, 96kHz hi-resolution recording & mastering

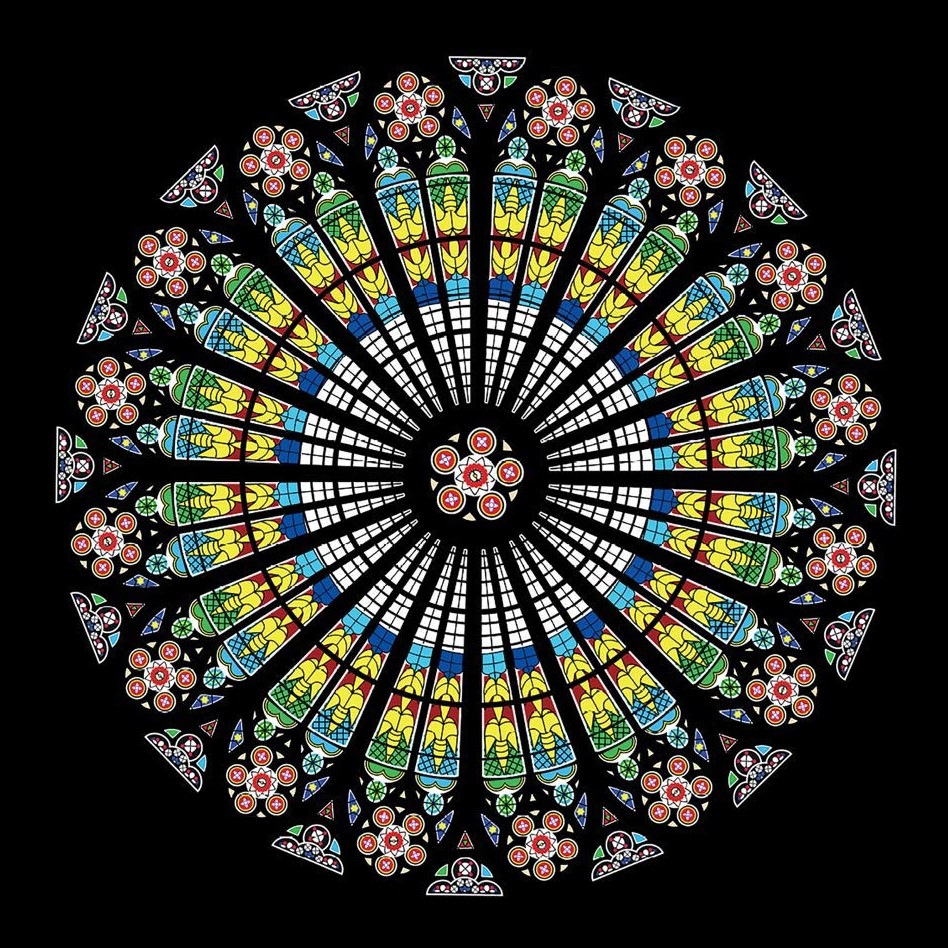

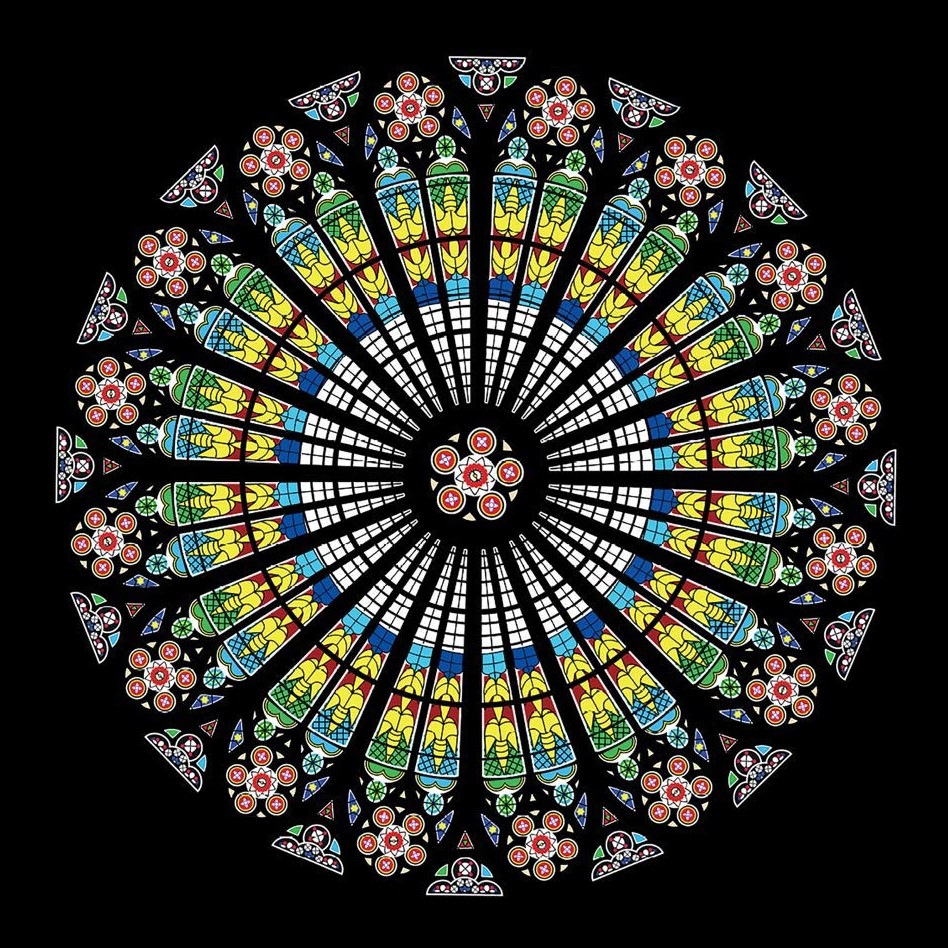

Album cover image by Silvie Mišková based on the

13th-century rose window of Strasbourg Cathedral, under licence from

Shutterstock.com

All photos taken by Robert Piwko

Artwork by David Murphy (FHR)

Manuscripts:

Page 4. Rosa das rosas (Cantigas de Santa Maria),

page 7: Procession from Ordo Virtutum (Riesencodex),

page 14: O virgo pia • Lis ne glai (Montpellier Codex),

page 17: Ciconia O rosa bella (Paris Bibliothèque Nationale),

page 19: Laude novella sia cantata (Laudario di Cortona)

℗ & © 2018 The opyright on this sound recordings is owned by Frist Hand Records Ltd

www.firsthandrecords.com

The Telling would like to thank all the people who supported our

Crowdfunding appeal

and who made donations or pre-ordered the album.

We

couldn't have made this album without you!

Many thanks too, to our

wonderful recording engineer Adrian Hunter and to First Hand

Records for all their help and support.

FHR thanks Peter Bromley and The Telling

Gardens of Delight — Roses, Lilies and Other Flowers in Medieval Song

Ego flos campi et lilium convallium. Sicut lilium inter spinas sic amica mea inter filias

(Song of Songs, Chapter 2, verses 1-2)

References to lilies and roses and many other flowers abound in both

secular and sacred texts that were set to music from across European

medieval repertoire from the 12th to the early 15th century. These two

flowers in particular provided a rich symbolism: lilies represented

purity and brightness in a sacred context. Roses are often used to

represent love, secular or sacred. Both flowers were strongly

associated with the Virgin Mary — the lily particularly is

associated with the annunciation, the biblical scene in which the Angel

Gabriel appears to Mary to announce that she will give birth. Countless

painting and altarpieces show Gabriel presenting a lily to Mary.

Myriad medieval song texts survive which place lilies, roses —

and flowers in general — centre stage and this album highlights

just a small selection, encompassing a wide range of textures and

styles from across the Middle Ages. There are early examples including

simple anonymous Italian laude

(congregational songs), the distinctive chant by 12th-century medieval

abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) known for her repeated use of

greenness and lushness as a metaphor for the Virgin's fedundity. At the

other end of the spectrum are florid virtuosic pieces of the late 14th

ancLearly 15th century which push at the boundaries of rhythm and

tonality, exemplified by the stunning Un fiore gentil m'apparse by Antonio Zacara de Teramo (1350-1415) and O Rosa bella, o dolce anima mia by Johannes Ciconia (1370-1412).

There is also music by Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377), the beautiful English medieval carol Ther is no rose of swych virtu, earthly German love songs, one of the most popular songs from the Spanish collection of King Alfonso el Sabio, the Cantigas de Santa Maria and a soulful song from the Sephardic Jewish tradition La rosa enflorese.

The modern preoccupation with pigeon-holing and categorising was foreign to composers(1) of the Middle Ages; the lines between sacred and seculair were distinctly blurred. This can be seen in

the striking similarity in use of floral imagery, particularly of the

lily and the rose, in both secular and sacred texts, even when the mood

and context of the music is quite different.

Composers often brought together sacred and secular texts and melodies

in the same piece. The French section includes an example from the Montpellier Codex

(13th century) where the composer consciously sets two different texts

in the upper two lines, both of which celebrate the lily in a sacred

and a secular context over a cantus firmus (O virgo pia — Lis ne glai — Amat):

'O pious Virgin, lily bright beyond all lilies... / Neither lily nor

gladiola nor rosebush in bloom, nor birdsong... cause me to rejoice and

compose my song: this I do... because of love, who put me in prison'.

In Plus bele que flor — Quant revient et fuelled et flor — L'aurtier joer mén alia — Flos

three different secular texts are sung above the lowest 'tenor' line,

played by the harp, which comes from the gregorian chant 'Stirps

Jesse', sung on feastciays in honour of the Virgin Mary.

© 2018 Clare Norburn

1 The concept of 'composer' as opposed to simply 'musician'

did not come about until some time after the Middle Ages, including the

music heard on this album; the 'writer' of the music was probably only

rarely the musician who had created the music. 'Anonymous' was, in

truth, a collective of creators.

The Telling has a growing reputation for creating intimate, staged

concerts to bring medieval music off the page and reach wider

audiences. They create a different concert experience, combining

ballads and upbeat instrumental dances with new writing, narrative,

readings or film. They sometimes perforrn whilst moving around the

audience, using lighting and/or candlelight.

'a multimedia experience of light, song, music & storytelling (The Argus)

Formed in 2009, The Telling draw from a pool of leading musicians who

perform for the Society of Strange & Ancient Instrurnents, I

Fagiolini, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Carnival Band and The

Dufay Collective.

'sung with perfection that is heart-stopping' (Worthing Herald)

The Telling has performed regularly at Brighton Early Music and is

resident at the Stroud Green Festival, North London. Recent engagements

include the Buxton International Festival, Colchester Early Music

Series, Leamington Music, the Hastings Early Music Festival, Omnibus

Theatre, Kino Teatr (St Leonard's-on-Sea) and Stoke Newington Early

Music Festival.

'beautifully born' (Sean Rafferty, BBC Radio 3)

Aiming to transforrn access to medieval music, The Telling is

establishing a series of residencies initially targeting Liverpool,

Hastings, Worthing and South-East Devon. The Telling also has a busy

schedule of UK festival engagements — see www.thetelling.co.uk for a current listing.

Clare Norburn is a soprano and

playwright. She studied music at Leeds University and London College of

Music. Apart from The Telling, she has sung as a soloist with many

medieval ensembles including Medita (who were finalists in the York

International Young Artists Competition and selected for Southbank

Centre's Fresh Young Artists Series), Eclipse and Vox Animae with whom

she has recorded and performed medieval abbess, Hildegard of Bingen's

music drama Ordo Virtutum.

She has performed throughout the country as a soloist including at The

Purcell Room, The Bridgewater Hall and at leading festivals including

Spitalfields Music, Brighton Festival, Newbury Spring Festival and

Buxton Festival.

Since 2010 Norburn has been developing a new genre of concert/plays for

actor(s) with live music. Her Beethoven's Quartet Journey (a cycle of 6

concert/plays to accompany a full cycle of all Beethoven, string

quartets) was developed with funding from Arts Council England and

premièred in Lympstone, Devon and has been featured on Radio 4's

Today programme. Extracts were also performed at the Southbank Centre's

Study Day in October 2017.

Norburn's third concert/play, Breaking the Rules,

received a 4-star review in The Guardian who wrote it was a 'vivid and

daring one-man psychodrama'. The work is a collaboration with vocal

ensemble The Marian Consort, actor Gerald Kyd, who plays the composer

and murderer Carlo Gesualdo, and director Nicholas Renton. It was

performed in 17 major UK festivals between 2016-2017 including the

Cheltenham, Bath, Newbury, Brighton, Buxton and Lichfield Festivals,

funded by the Arts Council England, and was also recently performed at

LSO St Luke,. It will tour again in 2019 to Bridgewater Hall and St

George's Bristol. Norburn has also written three shows about women

(including the medieval Abbess Hildegard of Bingen) for The Telling.

Together with soprano Deborah Roberts, Norburn co-founded the Brighton

Early Music Festival, stepping down in 2017 after 15 years.to

concentrate on writing and singing. She is Artistic-Director of the

Stroud Green Festival. She trains and mentors young ensembles for the

National Centre for Early Music, Handel House, the Royal Academy of

Music and the Guildhall School of Music 8, Drama. She ran the Early

Music Live! scheme for 10 years at Brighton Early Music, and has

supported a number of young ensembles at the Stroud Green Festival,

helping them develop new projects, secure bookings with promoters and

funding.

Ariane Prüssner was born

in Hanover, Germany, where she studied opera for four years at the

Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien Hannover before coming to

London with a scholarship from the German government to do a

postgraduate course at the Royal Academy of Music wherer she obtained a

Recital Diploma. She subsequently won grants to study song repertoire

and contemporary opera at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Banff,

Canada.

Prüssner has sung as a soloist in the oratorio repertoire and in

song recitals all over Britain, Including Brahms songs at the Purcell

Room, Handel's Messiah at Lincoln Cathedral, Bach Cantatas at St George's Hanover Square and Brahms' Alto Rhapsody

at Sewell Cathedral. She fell in love with medieval music and, along

with Clare Norburn, joined groups including Fifth Element, Third Voice

and Mediva.

After moving to Barcelona, Prüssner sang with the Chamber Choir of

the Palau de la Música Catalana, touring Europe with Marc

Minkowski and the Musiciens du Louvre, Jean Christophe Spinosi and the

Ensemble Matheus, as well as performing as a soloist at the Palau de la

Música in, among others, Handel's Israel in Egypt and Vivaldi's Gloria.

She has recently returned to the UK, and now lives in Hastings where

she has a growing singing teaching practice. She performs and records

with The Telling including performances at the Little Missenden

Festival, Brighton Early Music Festival, the Buxton Festival and Music

at Oxford.

Leah Stuttard hails from a

Lancashire mill town and has played the medieval harp for over 20

years. The first medieval music she loved was on scratchy

out-of-circulation David Munrow LPs that she bought for $l from the

local library. She has worked with famous names such as Jordi Savall

and appeared around the world from Mexico to Russia. For over 15 years

she has worked with the lively Italian group, Micrologus and continues

to provide them with a certain Anglo-Saxon je ne sais quoi. She has

created two solo projects thanks to funding from the Medieval Song

Network and a commission from the Copenhagen Renaissance Music

Festival. In France where she now lives she works with the group La

Camera delle Lacrime and she also loves singing and playing with her

Nordic partner in (creative) crime, Agnethe Christensen. With her, she

has performed across Norway, Sweden, Italy, Estonia, Denmark and the UK.