medieval.org

Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" SAWT 9486-A

1966

CD, 1998: Teldec "Das Alte Werk" 3984-21 804-2

medieval.org

Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" SAWT 9486-A

1966

CD, 1998: Teldec "Das Alte Werk" 3984-21 804-2

(A)

Stefan MAHU (c.1490—1540)

1. Es gieng ein wolgezogner knecht [1:23]

mezzo-soprano, tenor C, 2 viols, lute

2. Es wolt ein meydlin wasser holn [2:14]

mezzo-soprano, portative, rauschpfeife, crumhorn, viol

3. Ein meidlein tet mir klagen [1:52]

baritone, 3 viols

4. Ein pauer gab sein son ein weib [2:31]

mezzo-soprano, tenor R, baritone, kortholt, crumhorn, viol

Ludwig SENFL (c.1480—1542)

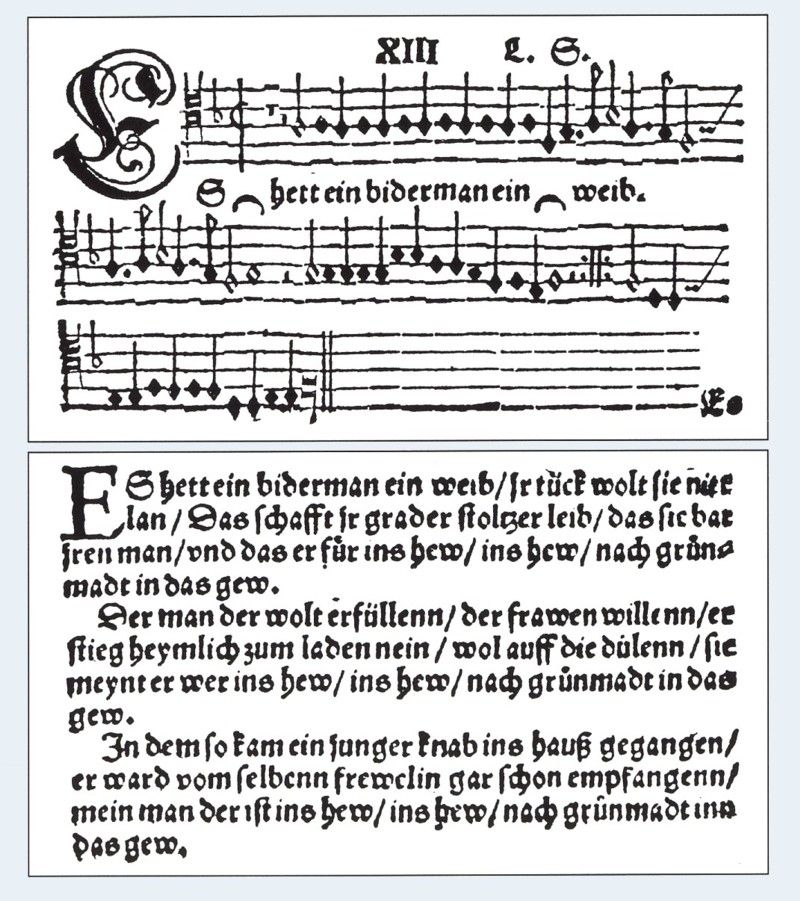

5. Es hett ein biderman ein weib [2:10]

mezzo-soprano, tenors C R, baritone, 4 crumhorns

6. Es wolt ein fraw zum Weine gan [0:52]

baritone, 3 crumhorns

7. Ich het mir ein endlein fürgenommen [0:47]

mezzo-soprano, tenor C, viol, lute

8. Die prünle, die da fließen [1:08]

tenor C, 3 viols

Ludwig SENFL

9. Ich stund an einem morgen [3:03]

tenor R, portative, viol, lute

10. Es taget vor dem Wald [1:39]

tenor C, baritone, 3 viols

11. Es warb ein schöner jüngling [1:41]

mezzo-soprano, 3 viols

Ludwig SENFL

12. Quodlibet. Es taget vor dem Wald - Es warb [1:04]

mezzo-soprano, tenor C, 2 viols

13. Es ist ein schnee gefallen [1:38]

mezzo-soprano, lute (arr. Thomas Binkley)

Thomas STOLTZER (c.1480—1526)

14. Entlawbet ist der walde [4:15]

tenor C, 3 viols

(B)

Ludwig SENFL

15. Ich weiß nit was ehr ihr verhieß [1:01]

mezzo-soprano, tenor R, baritone, cornetto, viol

16. Im maien [1:54]

tenor R, flute, portative, viol

17. Den meinen Sack [1:36]

mezzo-soprano, crumhorn, viol

18. Der Vechlienlin [2:04]

baritone, 2 crumhorns, viol

19. Ich trau keinm alten - Ach guter gsell [5:44]

mezzo-soprano, tenor C, rauschpfeife, 2 crumhorns, viol

Ludwig SENFL

20. Im bad wöl wir recht frölich sein [2:27]

baritone, crumhorn, viol, lute

21. Ich weet en Vrauken amorues [1:57]

tenor C, rauschpfeife, crumhorn, viol

Ludwig SENFL

22. Ich armes megdlein klag mich ser [3:40]

mezzo-soprano, 3 viols

23. Nun zu disen zeyten [1:33]

mezzo-soprano, tenor R, crumhorn, viol

24. Den besten vogel den ich weiß [1:33]

mezzo-soprano, tenor R, viol, viol

STUDIO DER FRÜHEN MUSIK

Early Music Quartet

Thomas Binkley

Andrea von Ramm, mezzo-soprano, portative

Thomas Binkley, lute, crumhorn, rauschpfeife, kortholt, flute

Willard Cobb, tenor, crumhorn

Sterling Jones, viol, crumhorn

&

Nigel Rogers, tenor (#4, 5, 9, 15, 16, 23, 24)

Karl Heinz Klein, baritone

Johannes Flink, viol

Udo Klotz, viol

Don Smithers, cornetto

Recorded AEG Studio, Munich, Germany,

08/1963 (tracks #4, 5, 9, 15, 16, 23, 24) & 04/1966

Ⓟ 1964 TELDEC

CD, digitally remastered © 1998 TELDEC

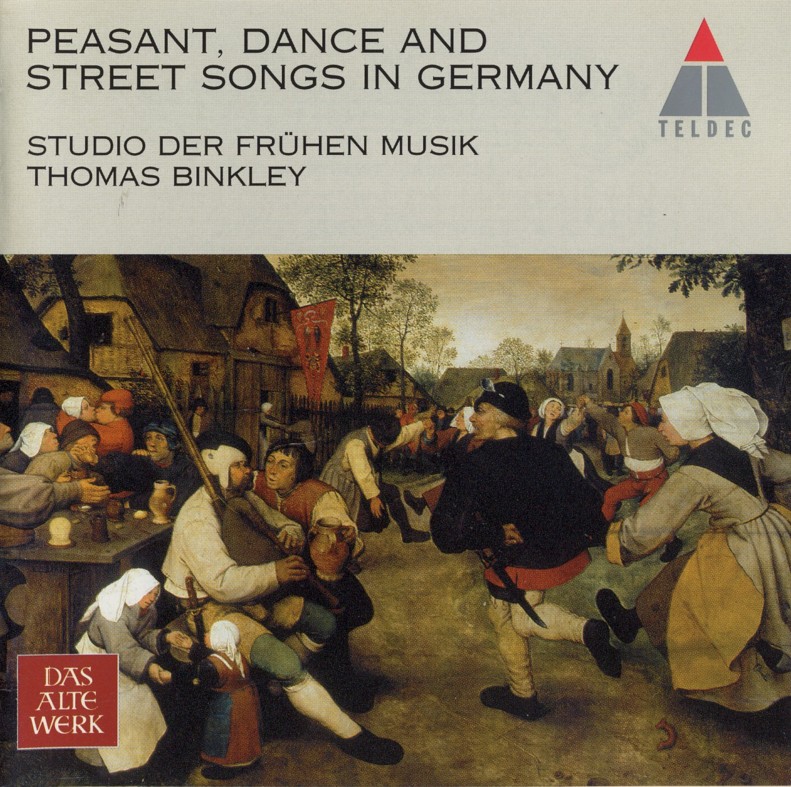

Cover: Peasant Dance, painting by Pieter Brueghel the elder (c1525-1569)

(Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin)

This

is a collection of witty, bucolic, and popular German songs from the

early 16th century, the age of the emperor Maximilian and of Dürer,

Erasmus, and Luther. They were genuinely popular, and quite different to

the serious repertory of the humanists or the love songs of the courts.

In fact, the ballads and songs of the townsfolk were full of burlesque

fun, satire, and earthy humour. It is true that humanists such as Konrad

Celtes and Joachim Vadian criticized certain composers and indeed the

frivolity of the whole genre. However, the very same composers continued

to be held in high esteem on account of their serious religious music.

And arranging popular songs was clearly something which they found

rather amusing, for there are numerous examples of a composer making

more than one arrangement of the same song.

In fact, making

arrangements of what was often simply referred to as "borrowed material"

was a standard feature of the contemporary composer's art. (Similarly,

research into such arrangements has now become a common musicological

pastime.) Regional styles of arrangement were in some ways related to

the predominant national style of composition. For example, around 1500

German arrangements were nearly always in four parts, with the melody in

the tenor voice. They were designed for a singer accompanied by two

treble instruments and a bass. However, the complexity of the various

arrangements differed significantly. Although simple settings in the

style of a chorale were not uncommon, many composers preferred to weave

interesting contrapuntal lines into the accompaniment, and to make

extensive use of imitation and canon. In the course of time popular

songs began to be turned into unaccompanied madrigals. Sometimes, as in

the case of the quodlibet, a number of songs were included in a single

madrigal. This heralded the decline of the genre, the success of which

had depended on its solo narratives, its charming naivety, and its

personal character. Without these features, the songs lack immediacy and

a specifically bucolic character.

In the 16th century regional

traditions and preferences were the source of major stylistic

differences. Thus it is no accident that the styles personified by Dürer

and Michelangelo, who were contemporaries, were so strikingly

different. In music, stylistic traditions existed not only in the field

of composition, but also in that of performance. There were clearly

distinct regional styles, which included the preference for certain

instruments and the style of singing. In Italy, for example, string

instruments were considered to be more "noble" than "vulgar" winds: the

Apollonian principle had triumphed over the Dionysian one. For this

reason string instruments tended to be used in the aristocratic circles

which patronized both composers and performers. However, German

aristocrats were obviously not as Apollonian as their Italian

counterparts. Nor were their tastes as sophisticated. In Germany

instruments were not employed symbolically, and there was no Castiglione

to proclaim the nobility and superiority of string instruments.

In

Italy and France the culture of the courts was considered to be refined

and sophisticated, and that of the street crude and unpolished.

However, in Germany a distinction tended to be drawn between the culture

of the city (which was deemed to be high) and that of the country

(which was considered to be low). Similar traditions and predilections

governed the treatment of instruments. Thus the evidence at our disposal

can help us to solve the problem of instrumentation. The notion that

Renaissance music was not written for specific instruments is

questionable, for we know which instruments tended to be grouped

together. For example, the trombone and cornett were often used with

voices, the lute with viols, the crumhorn with shawms and a trombone,

and so on. It is usually possible to discover the best and what was

probably the original instrumentation by adhering to such guidelines,

and by bearing in mind the character of the instruments and their

specific musical qualities.

The music on this CD was popular in

origin and popular in character. And it was designed for popular

consumption. As such it affords a unique insight into an aspect of life

in Renaissance Germany. Its most striking quality is humour, and it

depicts common attitudes towards institutions and human frailty which

were no doubt shared by contemporary listeners.

Thomas Binkley (1966, rev. 1998)

Teldec "Das Alte Werk" 3984-21 804-2

Vierzig Jahre jung: DAS ALTE WERK

Selten

gelingt es, ein Programm über einen solchen Zeitraum immer wieder mit

neuem Leben, mit neuen Impulsen zu füllen. Dem ALTEN WERK ist es

gelungen. Die Idee: hochprofessionelle Interpretationen auf

Originalinstrumenten. 1958 erschienen die ersten Schallplatten des ALTEN

WERKS, noch in Mono und aus schwarzem PVC gepreßt. Man hatte eine gute

Hand bei der Auswahl der Interpreten: Sie sollten stilbildend werden,

und ihre Aufnahmen können heute historischen Rang beanspruchen. Vor

allem in Holland wirkende Musiker um Gustav Leonhardt kamen Anfang der

60er Jahre zum ALTEN WERK: So Frans Brüggen, der mit stupender

Virtuosität die Blockflöte von den Zwängen des Banalen der

Gemeinschaftsmusik befreite. so der Cellist Anner Bylsma und der Geiger

Jaap Schröder. Geistesverwandt, wenn auch aus einer ganz anderen Region

stammend: Nikolaus Harnoncourt mit seinem Concentus musicus Wien. Der

junge Harnoncourt sollte dann auch die wichtigsten künstlerischen

Impulse bringen — und er ist seit seinen ersten Aufnahmen für Teldec

1963 dem Label treu geblieben: Von Monteverdi bis zu Mozart reichen

seine unzähligen Aufnahmen für das ALTE WERK, die ganze Vielfalt der

barocken Musik umfassend. Einen Schwerpunkt bildeten sämtliche

geistliche Kantaten Bachs; ein Projekt, das sich Hamoncourt und

Leonhardt teilten und das im Bach Jubiläumsjahr 1985 abgeschlossen

werden konnte. Von Anfang an hat DAS ALTE WERK Musik auch jener Epochen

vorgestellt, die erst in jüngeren Jahren auf breiteres Interesse

gestoßen sind: Die Vokalmusik der Renaissance sang die Capella Antiqua

München unter der Leitung von Konrad Ruhland. Und Thomas Binkley und

sein Studio der Frühen Musik erfüllten mittelalterliche Quellen mit

musikantischen Leben. Auch wenn das gesamte Spektrum von Gregorianischen

Hymnen und mittelalterlichen Tänzen bis zu Schuberts Sonaten auf dem

Fortepiano und den Streichersinfonien des jungen Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

im ALTEN WERK erschienen ist: immer stand und steht die Qualität der

Musik und ihrer Interpreten im Vordergrund. Das macht die Aufnahmen des

ALTEN WERKS, worunter sich viele Ersteinspielungen befinden, so

interessant. In neuester Zeit hat DAS ALTE WERK mit dem Cembalisten und

Pianisten Andreas Staier, mit dem Concerto Köln und mit dem

italienischen Ensemble II Giardino Armonico Künstler vorgestellt, die

der alten Idee faszinierend neue Seiten abgewonnen haben. Und es sieht

so aus, als ob Das ALTE WERK weiterhin so jung bleibt wie in seinen

ersten vierzig Jahren.

In den 60er Jahren entsprachen die vier Musiker des Studios der Frühen Musik rein äußerlich dem normalen Erscheinungsbild des Musikers; die Herren in Fliege und Frack, die Sängerin Andrea von Ramm

im Abendkleid. Doch das war alles, was dieses Ensemble mit der

herkömmlichen Musik gemein hatte. Man spielte auf so exotischen

Instrumenten wie dem Rebec und dem Pommer, und die 1928 geborene Andrea

von Ramm sang mit ganz eigentümlicher, fast androgyner Tongebung. Hier

erklang eine Musik, die beides war: alt und gleichzeitig unglaublich

aktuell. Nicht von ungefähr hatte sich die Sängerin vorher mit neuer

Musik beschäftigt. Damit bildete das Studio der Frühen Musik, das der

1931 geborene amerikanische Lautenist Thomas Binkley 1960 in

München gründete, einen Stil, der später von Musikern wie David Munrow

aufgegriffen wurde und dank der vielen Schallplatten des Ensembles in

alle Welt hinausgetragen wurde.

Die Stammbesetzung bestand neben dem 1995 gestorbenen Binkley und Andrea von Ramm aus dem Amerikaner Sterling Jones (alte Streichinstrumente) und dein Engländer Nigel Rogers (Tenor, Schlaginstrumente), der schon bald von einem anderen Engländer, von Willard Cobb, und später dann von Richard Levitt abgelöst wurde.

Die

Teldec hatte frühzeitig die Meriten des Ensembles entdeckt und

produzierte viele mit den vier Musikern und einer Reihe von

«Gastkünstlern« Repertoirelücken des Mittelalters und der Renaissance,

Aufnahmen, die durchgängig die Kritik begeisterten. Bis 1977 bestand das

Studio der Frühen Musik; in den knapp zwei Jahrzehnten seines Wirkens

entstanden etwa 50 Schallplatten — Aufnahmen, die Geschichte gemacht

haben.

Martin Elste

Forty Years young: DAS ALTE WERK

From a purely physical standpoint, the four members of the Studio der Frühen Musik looked just like any other musicians of the 1960s: the men disported themselves in tie and tails, while the soprano Andrea von Ramm

wore evening dress. But that was all that these musicians had in common

with traditional forms of music-making. They played on exotic

instruments such as the rebec and shawm, while Andrea von Ramm's singing

had a strange, almost androgynous quality to it. The result was a kind

of music that was both old and incredibly new. It was no accident that

Andrea von Ramm, who was born in Estonia in 1928, had earlier been

associated with contemporary music. In this way, the Studio der Frühen

Musik helped to forge a style of performing early music that was later

taken up by other musicians such as David Munrow and carried all round

the world in the form of the ensemble's innumerable gramophone

recordings.

Only rarely is it possible to breathe new life into one and the selfsame product over such a lengthy period of time and

keep on investing it with new ideas. But DAS ALTE WERK has done just that

with its underlying idea of presenting supremely professional

performances on period instruments. The first recordings on the DAs ALTE

WERK label appeared in 1958 — still in mono and in the form of black

vinyl discs. But fate had dealt the label an excellent hand in its

choice of performing artists, all of whom were to prove influential in

creating a specific style, so that their recordings can now lay claim to

historic status. Above all, it was artists living in the Netherlands

and associated with the figure of Gustav Leonhardt who came to DAS ALTE

WERK in the early 1960s. Here one thinks not only of Frans Brüggen,

whose stupendous virtuosity freed the recorder from its banal reputation

as an instrument for schoolchildren, but also of the cellist Anner

Bylsma and the violinist Jaap Schröder. Spiritually akin to these

musicians, but from a different part of Europe, is Nikolaus Harnoncourt

and his Vienna Concentus musicus. Indeed, it was the young Harnoncourt

who was to provide the label with its most important artistic stimuli

and who has remained loyal to Teldec since his very first recordings for

the company in 1963. His countless later recordings for DAS ALTE WERK

range from Monteverdi to Mozart and cover the whole vast span of Baroque

music in all its manifold guises. One particular focus of interest was

his complete recording of all Bach's sacred cantatas in the form of a

project divided between himself and Gustav Leonhardt and completed in

1985 to mark the tercentenary of the Thomaskantor's birth. From the very

outset, DAs ALTE WERK has featured music from periods that only later

have met with more widespread interest: Renaissance vocal music, for

example, was recorded by the Munich Capella Antigua under the direction

of Konrad Ruhland, while Thomas Binkley and his Studio der Frühen Musik

breathed new and vibrant life into their medieval goliardic sources.

Although the range of music that has appeared on the Dm ALTE WERK label

extends from Gregorian chant and medieval dances to Schubert sonatas

played on a fortepiano and the young Felix Mendelssohn's string

symphonies, it is the quality of the music and its performers that has

always been to the fore. It is this — and the fact that Das ALTE WERK

has featured many works never previously recorded — that makes these

recordings so interesting.

Among recent artists and ensembles to

appear on the DAS ALTE WEAK label are the harpsichordist and

fortepianist Andreas Staier, the German ensemble Concerto Köln, and the

Italian group Il Giardino Annonico, all of whom have shed fascinating

new light on the old idea. It looks very much as though DAS ALTE WERK

will continue to renew itself and remain as eternally youthful in the

future as it has done during its first forty years of existence.

The Studio der Frühen Musik was founded in 1960 by the American lutenist Thomas Binkley (1931-1995) and centred on three performers: Binkley himself, the American string player Sterling Jones and the English tenor Nigel Rogers, who also doubled as percussionist and who was later succeeded by another English musician, Willard Cobb, and, finally, by Richard Levitt.

Teldec

discovered the ensemble's qualities at a very early date and made many

recordings with the four members of the Studio der Frühen Musik, who

were joined on these occasions by a whole series of guest artists and

who in this way filled many gaps in the recorded repertory of medieval

and Renaissance music, recordings that were invariably enthusiastically

received by critics. By the time that the Studio der Frühen Musik was

disbanded in 1977 it had made some fifty recordings, all of which made

gramophone history.