paulrans.com | anz.be

muziekweb.nl | discogs.com

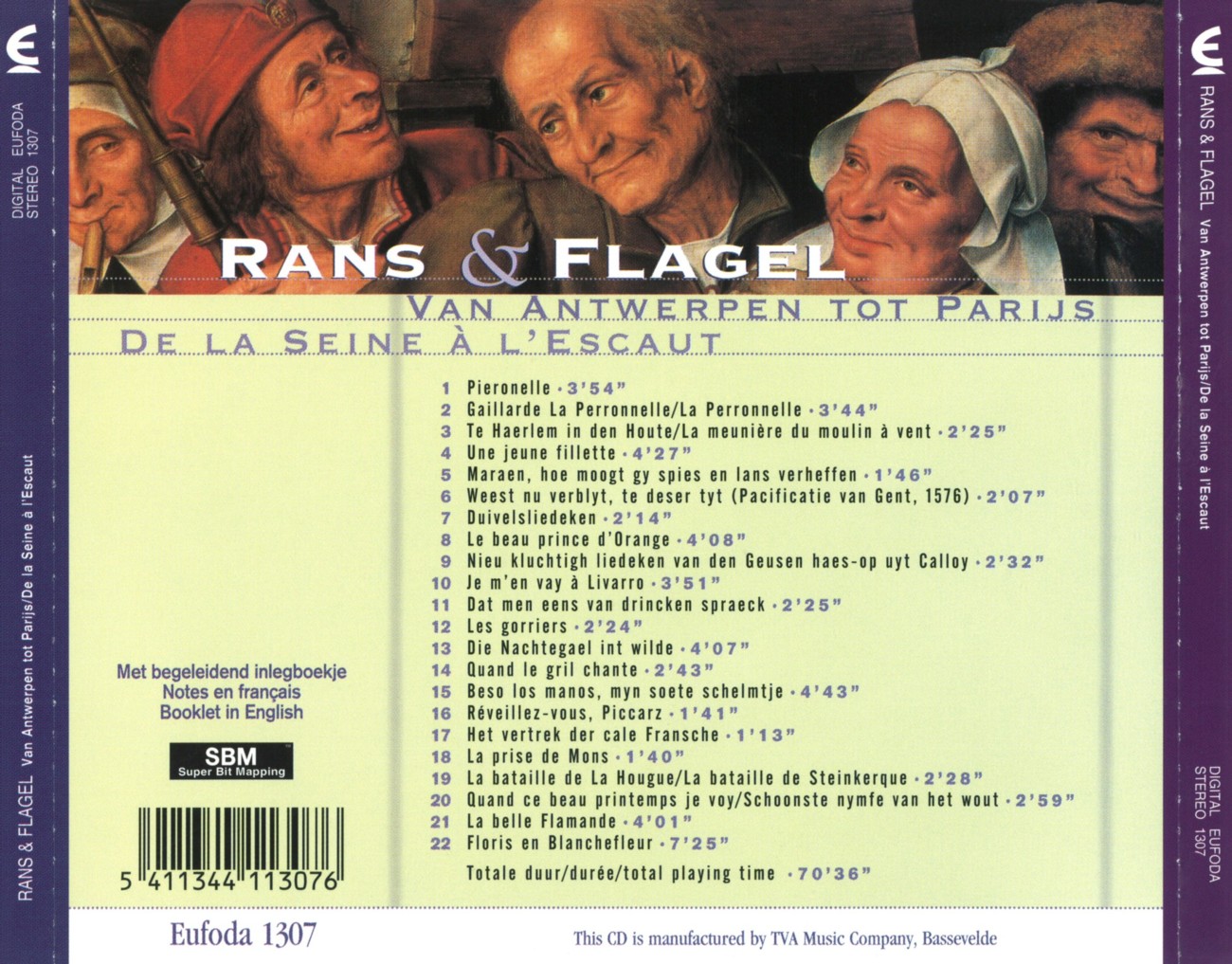

Eufoda 1307

2001

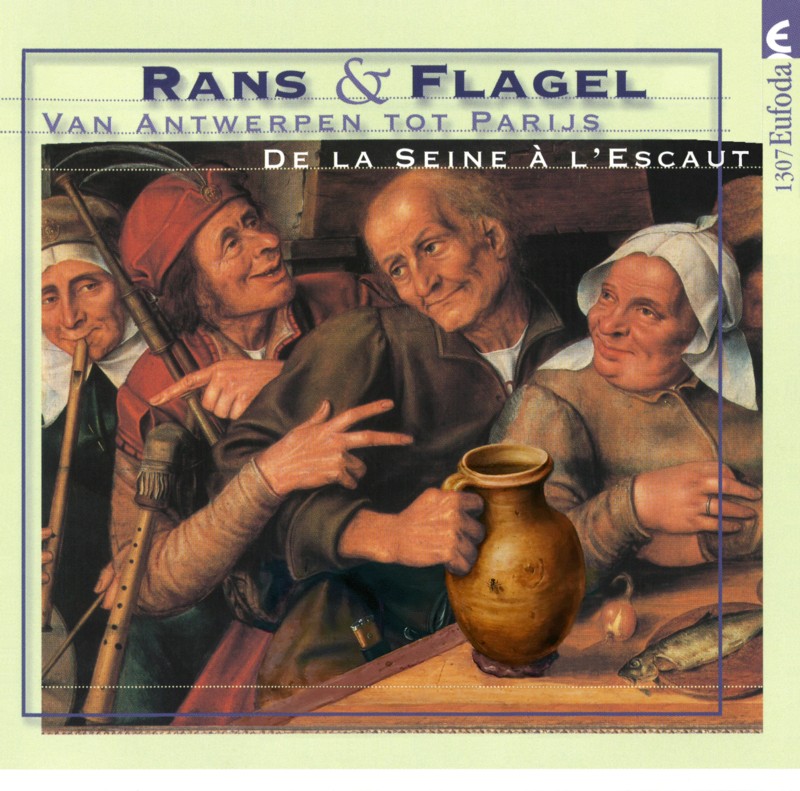

Van Antwerpen tot Parijs / Rans & Flagel

De la Seine à l'Escaut

paulrans.com |

anz.be

muziekweb.nl |

discogs.com

Eufoda 1307

2001

1. Pieronelle [3:54]

2. Gaillarde La Perronnelle/La Perronnelle [3:44]

3. Te Haerlem in den Houte/La meunière du moulin à vent [2:25]

4. Une jeune fillette [4:27]

5. Maraen, hoe moogt gy spies en lans verheffen [1:46]

6. Weest nu verblyt, te deser tyt [2:07] (Pacificatie van Gent, 1576)

7. Duivelsliedeken [2:14]

8. Le beau prince d'Orange [4:08]

9. Nieu kluchtigh liedeken van den Geusen haes-op uyt Calloy [2:32]

10. Je m'en vay à Livarro [3:51]

11. Datmen eens van drincken spraeck [2:25]

12. Les gorriers [2:24]

13. Die Nachtegael int wilde [4:07]

14. Quand le gril chante [2:43]

15. Beso los manos, myn soete schelmtje [4:43]

16. Réveillez-vous, Piccarz [1:41]

17. Het vertrek der cale Fransche [1:13]

18. La prise de Mons [2:40]

19. La bataille de La Hougue/La bataille de Steinkerque [2:28]

20. Quand ce beau printemps je voy/Schoonste nymfe van het wout [2:59]

21. La belle Flamande [4:01]

22. Floris en Blanchefleur [7:25]

PAUL RANS

zang, luit /

voice, lute

CLAUDE FLAGEL

zang, draailier, trom /

voice, hurdy-gurdy, drum

OLLE GERIS

doedelzakken, zang /

bagpipes, voice

PHILIPPE MALFEYT

luit, theorbe, cister, colascione, hakkebord, percussie, zang /

lute, theorbo, cittern, colascione, hammered dulcimer, percussion, voice

PIET STRYCKERS

viola da gamba, barokcello, colascione, zang /

viol, baroque cello, colascione, voice

AN VAN LAETHEM

barokviool, zang /

baroque violin, voice

PAUL VAN LOEY

blokfluiten, dulciaan, zang /

recorders, dulcian, voice

OPNAME EN MONTAGE/ RECORDING AND EDITING:

Sound Recording Centre Steurbaut, Gent

29.6.2001, 1-2.7.2001

SuperBit Mapping

20 bit digital recording on Sony PCM 9000 magnetic optical disc

ARTISTIEKE LEIDING/ PRODUCER: Johan Huys

GRAFISCHE VORMGEVING/ GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Daniël Peetermans

COVERILLUSTRATIE/ COVER ILLUSTRATION:

Jan Massys, Vrolijk gezelschap/ Merry Company

Wien, Kunsthistorisches Museum (foto: AKG Berlin/Erich Lessing)

Foto Rans & Flagel: Björn Tagemose

© 2001 Davidsfonds/Eufoda, Leuven

RANS & FLAGEL

VAN ANTWERPEN TOT PARIJS

DE LA SEINE À L'ESCAUT

Over België wordt graag gezegd

dat dit de plaats is waar de Germaanse en de Latijnse culturen elkaar

ontmoeten. Die wisselwerking tussen noord en zuid, waar vaak dezelfde

thema's in regionale varianten werden bezongen, die Vlaams-Waalse en

Nederlands-Franse voces populi, vormen de rode draad van het programma

dat Claude Flagel en Paul Rans presenteren in Van Antwerpen tot

Parijs/De la Seine à l'Escaut. Overigens ligt de oorsprong van

het repertoire soms ook wel iets verder af dan Parijs of Antwerpen.

Franse of Waalse en Vlaamse of Nederlandse liedjes wisselen elkaar af,

en vullen elkaar aan, begeleid door luit en blokfluit, gamba en viool,

draailier of doedelzak...

Hedendaagse uitvoerders fuseren graag

traditionele muziek en liederen uit verscheidene delen van Europa, of

zelfs uit de hele wereld. Zij versmelten dit repertoire tot wat nu

wereldmuziek heet. Die interactie tussen de verscheidene Europese

culturen heeft echter altijd al bestaan. Een puur, maagdelijk en

ongerept Vlaams (of Duits, Frans, Grieks...) volkslied is niet meer dan

een hersenschim. Wat nog niet wil zeggen dat er geen regionaal karakter

zou bestaan, maar onze gezamenlijke erfenis — zowel uit de

Griekse en Latijnse mythologie als uit het christendom — heeft op

het Europese volkslied een duidelijke stempel gedrukt. Dit Europese

volkslied-repertoire vormt één grote familie, waarin

verwante thema's en motieven bezongen werden (of warden) van

Scandinavië tot Sicilië en van de Oeral tot de Atlantische

Oceaan. Op grote en kleine school. En dus ook van Antwerpen tot Parijs.

De Vlaamse, Nederlandse, Waalse en

Franse liederen op deze cd illustreren hoe het Nederlandse en het

Franse taalgebied muzikaal en thematisch met elkaar zijn verbonden.

Stilistisch reflecteren de uitvoeringen vooral de geest van dit

repertoire, zonder het verleden letterlijk te willen hercreëren,

in een sfeer van Bourgondisch Vlaams tot hoofs Frans en omgekeerd.

It is often said that it is in Belgium that Latin and Germanic cultures

meet. In popular song the cross-fertilisation between North and South,

where similar themes were often sung in their regional versions in

Dutch and in French. These voices of Flemish and Walloon, and Dutch and

French people form the thread that binds together the present programme

offered here by Claude Flagel and Paul Rans. The title Van Antwerpen

tot Parijs/De la Seine à l'Escaut means, 'From Antwerp to

Paris/From the Seine to the Scheldt', but some of the repertoire comes

from either a little further North or further South. French or Walloon

and Flemish or Dutch songs alternate and complement each other,

supported by a variety of instruments — from lute, recorder and

bass viol to bagpipes and hurdy-gurdy.

Today's performers like to borrow traditional music and songs from

various parts of Europe or the world, and to fuse them into what is now

called world music. This is happening on a large scale, but there is in

fact nothing new in European cultures interacting and fertilising each

other. A pure and unadulterated Flemish (or French, German, Greek...)

folk song does not really exist. This does not mean of course that

there isn't such a thing as regional character, but our common heritage

from Greek and Latin mythology and from Christianity has left its mark

on European folk songs. They are part of one big family with themes and

motifs that run from Scandinavia to Sicily, and from the Ural Mountains

to the Atlantic Ocean. And from Antwerp to Paris.

The present programme shows a small part of this common heritage in a

repertoire of Flemish, Dutch, Walloon and French songs that are linked

musically and thematically. Stylistically the interpretations reflect

the spirit of this repertoire, rather than trying to produce literal

recreations of the post, and evoke an atmosphere that changes from

festive Flemish to courtly French and vice-versa.

1. Pieronelle

Haerlems Oudt Liedt-boeck, Haarlem, 1716 (stem: Ey, wilder dan wilt)/

Souterliedekens ghemaect ter eeren Gods, op alle die psalmen van David,

Antwerpen, 1540 ('na de wijse Roosken root, seer wijdt ontloken')/

Jan Fruytiers, Ecclesiasticus, Antwerpen, 1565, nr. 53 ('op die wijse Och roosken root')/

Jan Frans Willems, Oude Vlaemsche Liederen, Gent, 1848, nr. 106/

Florimond van Duyse, Het Oude Nederlandsche Lied, Antwerpen-Den Haag, 1903-1905, nr. 290/

Arr. Piet Stryckers

Pieronelle, a Flemish girl, is lured away by three frenchmen. Her three

brothers organise a search for her, but when they finally find her she

refuses to go back home. There she would have to suffer the disgrace of

having lost her honour and she prefers life with the frenchmen who have

a taste for good living and good wine.

2. Gaillarde La Perronnelle/La Perronnelle

Chorearum Molliorum, Antwerpen, 1583/

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. fr. 12.744/

Gaston Paris & Auguste Gevaert, Chansons du XVe siècle, Paris, 1875

In the French version Perronnelle is taken away by three gendarmes,

dressing her like a page-boy to take her out of the country. Her three

brothers find her eventually by a fountain and ask her to come home

with them, but she refuses to go back to France whilst, like the

Flemish girl, giving her fond regards to her parents. The popularity of

this French song is reflected in the galliard which Pierre

Phalèse published in Antwerp in 1583.

3. Te Haerlem in den Houte/La meunière du moulin à vent

Amsterdamsche Vreughde-Stroom, Amsterdam, 1655/

Luitboek van Thysius, 1621-1653. Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, hs. hys. 1666/

Florimond van Duyse, Het Oude Nederlandsche Lied, Antwerpen-Den Haag, 1903-1905, nr. 281/

Arr. Piet Stryckers —

Léonard Terry & Léopold Chaumont, Recueil d'airs de

cramignons et de chansons populaires à Liège,

Liège, 1889/

Albert Boone, Het Vlaamse volkslied in Europa, Tielt, 2000

Millers have always had a reputation as being ladies' men. In the Dutch

song the miller plans to serve wine to a girl's mother, hoping he'll be

able to take her daughter unnoticed to his bedroom. In the French song

a miller girl rebuts the advances of young colin, too worried about the

village gossips. The tune is obviously popular but the text may have a

more literary origin, although the refrain 'Par derrière et par

devant' occurs regularly in ribald songs from the 16th century to today.

4. Une jeune fillette

Jehan Chardavoine, Le recueil des plus excellentes chansons en forme de voix de ville, Paris, 1576

A young woman is forced to enter a convent, where she longs for her

lover. This unhappy theme was very popular and this version by

Chardavoine is the most complete. Five of the seven verses are sung

here. The tune was also used as a dance, Allemande Nonette, borrowed in

France for a Christmas carol which is still sung today. In the Low

Countries the tune was used for a song against the Spanish occupation

in the 16th and 17th centuries, Maraen, which follows the French

version here.

5. Maraen, hoe moogt gy spies en lans verheffen

Adriaen Valerius, Nederlandtsche Gedenck-Clanck, Amsterdam, 1626 (stem: Almande Nonette/Une jeune fillette)

'Maraen' was a word to designate the Spanish occupiers who, among other

injustices, forced the infamous Inquisition on the population. The

'geuzen' (literally 'beggars' but they carried the name with aride)

revolted against Spain and Catholicism and 'geuzen-songs' played an

important part in this historic fight which ended with the Netherlands

becoming independent and Protestant, whilst Flanders remained Catholic

under the rule of the Habsburgs. This song accuses the Spanish of

thinking that

they are above God, who is the true ruler of the world.

6. Weest nu verblyt, te deser tyt

(Pacificatie van Gent, 1576)

In November 1576 the Seventeen Provinces agreed to remain united in

eternal peace, getting rid of ail foreign troops. Catholicism remained

the official religion, except in Holland and Zealand where there was to

be freedom of religion under William of Orange. This song celebrates

this agreement, known as the Pacification of Ghent, and reflects the

brief feelings of hope and happiness — soon to be dashed.

7. Duivelsliedeken

Abraham Verhoeven, Den tocht van de Brandt-stichters, Antwerpen, 1622 (stem: Guillelmus van Nassouwe)

In May 1622 Frederic Henry of Nassau and

his troops looted and burned down great parts of the province of

Brabant. This song — a pamphlet from Antwerp — is against

the 'geuzen', satirising the cruelty and hypocrisy of so-called

God-fearing men in the dutch army. This is done to the tune of the

Wilhelmus, which became the Dutch national anthem, but here in a

ternary rather than the usual binary time.

8. Le beau prince d'Orange

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. fr. 12.666/

Arr. Piet Stryckers

The death of René of Nassau, the 'handsome prince of Orange',

who fought with Charles V against the French king François I. An

eye-witness brings a letter describing how he was killed in the battle

of Saint-Dizier (1544) and subsequently buried — a scene

reminiscent of that famous song Malbrouck s'en va-t-en guerre, but

preceding it by two centuries. The French did not like this handsome

prince and made it clear in the derisory tone of the song.

9. Nieu kluchtigh liedeken van den Geusen haes-op uyt Calloy

Maurits Sabbe, Brabant in 't verweer, Antwerpen, 1931 (stem: Hebbense dat gedaen, doense, doense...)

This is a second song against the 'geuzen' who suffered a serious defeat

in Kallo on the river Scheldt in 1638. The Dutch had found an ally in

France to attack the Spanish in Flanders, but this was to no avail as

the Spanish troops managed to fight back the Dutch. Prince William of

Nassau's son was killed in the battle. This was to the taste of

pro-Catholic Flemings who satirised the 'geuzen' in this text set to a

well-known traditional Flemish tune.

10. Je m'en vay à Livarro

Jacques Mangeant, Recueil des plus belles chansons des comédiens françois, Caen, 1615

A very French drinking song with a tune that invites the singer (and

the piper) to let the voice reach high and far. Even in France eating

and drinking well was often associated with the vision of Flemish

feasts as depicted by Brueghel, Teniers, Van Ostade or Jan massjis (see

CD cover). Bacchanals such as this one make up about half of the songs

in Jacques Mangeant's collection of 1615.

11. Datmen eens van drincken spraeck

Jan Jansz. Starter, De Friesche Lusthof, Amsterdam, 1621

Drinking songs were as popular in the Low Countries as in France, and

this song — written in the style of chambers of rhetoric —

extols the benefits of drinking good wine (especially French) such as

making people talk, dance and sing: farewell wisdom, see you in the

morning.

12. Les gorriers

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. fr. 12.744/

Gaston Paris & Auguste Gevaert, Chansons du XVe siècle, Paris, 1875/

Arr. Piet Stryckers

In late 15th century Paris 'gorriers' were trendy young people who

liked to live in style but who lacked the means to do so. Gaston Paris

and Auguste Gevaert's research resulted in the publication of 143 songs

that were popular in France at the end of the 15th century. For many of

these songs this is the only source.

13. Die Nachtegael int wilde

Een Aemstelredams Amoreus Lietboeck, Amsterdam, 1589 ('op de voys Brande Matresse')/

Luitboek van Thysius, 1621-1653. Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, hs. Thys. 1666

A bilingual song, in Dutch but with a French chorus, set to a 'Brand'

or branle, one of the most popular French dances. The wording and the

story itself are wholly permeated by Frenchness: a lover pleads for his

lady to return his feelings, her heart is already taken, but — as

he threatens to take his life — she doesn't want to be ungenerous

and welcomes him as

well. Even if the pope was her father she would not forego the love of this faithful servant.

14. Quand le gril chante

Jehan Chardavoine, Le recueil des plus excellentes chansons en forme de voix de ville, Paris, 1576

This is a typical 'air de cour' which, supported by the lute, evokes an

idealised life of rural bliss. It cames from a collection of 153 songs

published in 1576 by Jehan Chardavoine. Many of these songs were not

only pleasant to listen to but also very suitable for dancing.

15. Beso los manos, myn soete schelmtje

Jan Jansz. Starter, De Friesche Lusthof, Amsterdam, 1621

A satirical song about the enthusiasm with which all nations keep going

to war, always to the detriment of the pensants. This is one of

Starter's coarse songs, the 'boertigheden' at the end of his Friesche

Lusthof. Jan Jansz Starter was of English descent, a 'minor poet' but

an excellent songwriter who liked to borrow tunes from other European

countries, including

England, Flanders and France. Of the eight verses six are sung here.

16. Réveillez-vous, Piccarz

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. fr. 12.744/

Gaston Paris & Auguste Gevaert, Chansons du XVe siècle, Paris, 1875

This song evokes the wars at the time of emperor Maximilian of Austria,

who opposed the kings of France as well as the Flemish towns until

1489. Wake up citizens of picardy and burgundy, it's time to go to war,

a sad state of affairs. The

duke of Austria is in the Low Countries, in Flanders with his Picards

who want to conquer Burgundy for him. Farewell Besançon and

Beaune, home of good wine. The Picards have drunk it and the Flemish

will have to pay. If they refuse they will be beaten up.

17. Het vertrek der cale Fransche

Ms. Di Martinelli, Diest, ca. 1743-1770 (P206). Leuven, Katholieke Universiteit/

Arr. Piet Stryckers

18. La prise de Mons

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. fr. 12.669 ('timbre Nous

voyageons parmi le monde')

The end of the 17th century was marked by the wars between France under

Louis XIV and the Augsburg League which was joined by the Low Countries

and England. The siege of Mons (in Wallonia) and the bombing of

Brussels which destroyed part of the Grand' Place are just two of the

many violent events of those years.

19. La bataille de La Hougue/La bataille de Steinkerque

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, ms. fr. 12.670 ('timbres La petite fronde/Les Rochellois')/

Arr. Piet Stryckers

Two defeats suffered by the French army in 1692, one at sea near La

Hougue, the other on land at Steinkerque (Steenkerke in the province of

Brabant). Both battles left many people dead, with winners and losers

exhausted and the singer complaining that too many glorious battles end

with funeral music.

20. Quand ce beau printemps je voy/Schoonste nymfe van het wout

Jehan Chardavoine, Le recueil des plus excellentes chansons en forme de voix de ville, Paris, 1576/

Den Bloemhof van de nederlantsche ieucht, Amsterdam, 1608 ('voys Bella nympha fugitiva')/

Florimond van Duyse, Het Oude Nederlandsche Lied, Antwerpen-Den Haag, 1903-1905, nr. 130

'Quand ce beau printemps je voy' (When I see this beautiful springtime)

is a poem by Pierre de Ronsard which was included in Adrien le Roy's

Airs de Cour (1571). The tune proved so popular that many contrafacta

were made in French, Dutch, German and Italian, setting it to bucolic,

political and even religious lyrics. There is a political Dutch

'geuzen-song', but this version dwells in the same pastoral spheres as

the original and is sung alternately with the french, to a slightly

different tune.

21. La belle Flamande

Patrice Coireault, Formation de nos chansons folkloriques, Paris, 1959

The French campaigns in Flanders consisted not only of battles. For the

French soldiers the wealth of the Flemish regions was often like a

vision of the land of Cockaigne. The beautiful Flemish girl of this

song has so many lovers that she doesn't know which one to choose and

the same proverbial girl features in numerous songs which became

popular throughout France.

22. Floris en Blanchefleur

Edmond de Coussemaker, Chants populaires des Flamands de France, Gent, 1856, nr. 51/

Arr. Piet Stryckers

The origin of this ballad is a medieval french poem, Flore et

Blanchefleur. This version was transmitted orally and collected by

Edmond de Coussemaker in the middle of the 19th century in French

Flanders (Northern France, formerly part of the Low Countries, where

older people still speak a Flemish dialect). Blanchefleur is not

allowed to marry the king's son and is sold to the Turkish emperor,

while her beloved Floris is told that she has died. He

finds out that she is alive and travels to Turkey where he manages to

find a way inside the palace, hiding in a basket which is pulled up with

a rope by Blanchefleur. He enters her room, they fall into each other's

arms and spend the night together. In the middle of the night the

emperor enters the bedroom and wants to kill them both, but they plead

for forgiveness. The emperor holds back, forgives them and lets them be

married in church which, after 19 verses (here somewhat shortened), is

a suitably happy end.