medieval.org

Giulia "Musica Antiqua" GS 201007

1991

[52:47]

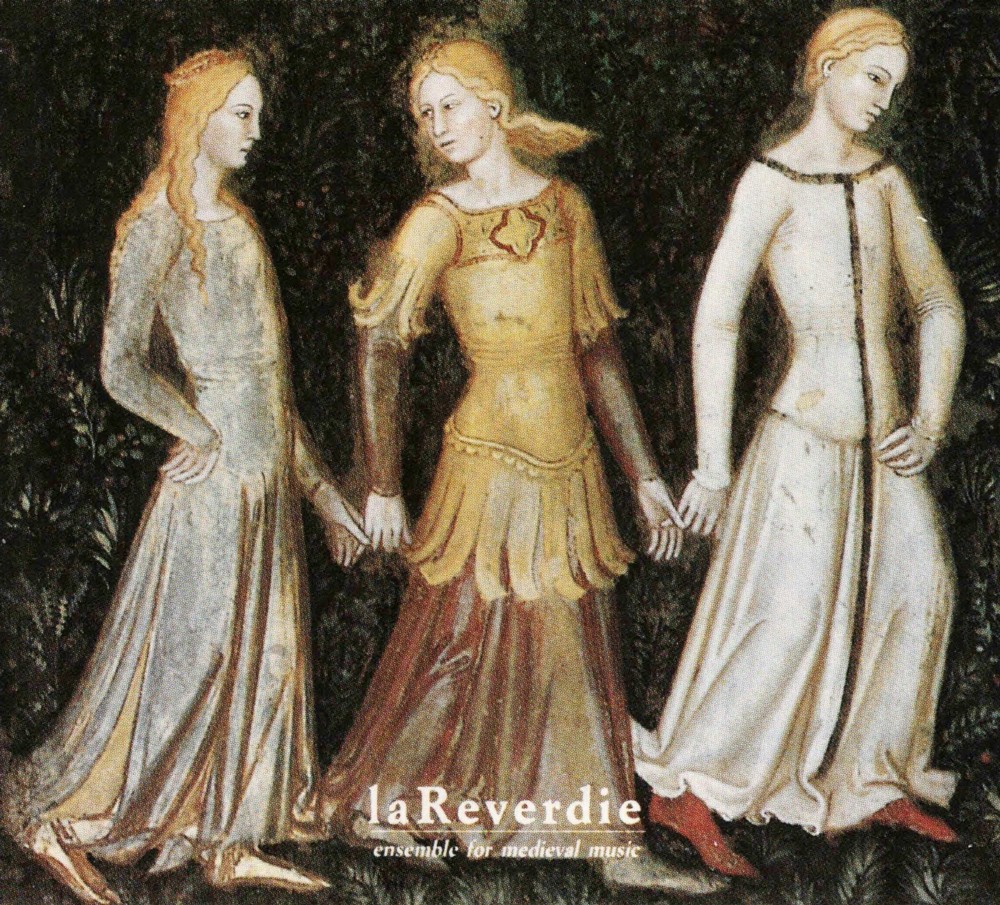

Guinevere, Yseut, Melusine / La Reverdie

The heritage of Celtic womanhood in the Middle Ages

medieval.org

Giulia "Musica Antiqua" GS 201007

1991

[52:47]

I. Serca • Amores

Ysôt ma drûe, Ysôt m'amie

en vûs ma mort, en vûs ma vie

Gottfried von Strassburg, Tristan, c. 1225

1. Lamento di Tristano [4:06]

monophonic instrumental piece · Anonymous Italian, 14th c. | British Museum, MS Add 29987

medieval harp 1, rebec, lute, recorder 4, percussion 1

2. La bionda trezza [2:57]

three-part ballata · Francesco LANDINI (1335-1397) |

Codice Squarcialupi

voices 1 2, gothic harp, rebec, fiddle, lute

3. Se Geneive, Tristan [3:40]

virelai à 3 · Johannes CUNELIER (14th c.) |

Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS 564

voice 2, lute, fiddle

4. Pucelete ~ Je langui ~ DOMINO [2:07]

three-part motet · Anonymous French, 13th c. |

Bamberg, Stiftsbibl., MS Ed. IV 6

voices 1 2, harp, lute, fiddle, percussion 2

II. Echtrai • Casus

& seu sai dir ni faire

ilh n'aja l grat, que siensa

m'a donat & conoissensa,

per qu'eu suis gai & chantaire

Peire Vidal, 12th c.

5. Ja nus hons pris [3:01]

accompanied monophonic song ·

Richard I the LIONHEART (1175-1199) |

Paris, Bibl. Nat., MS fr. 844

voice 1, medieval harp 1

6. Di nuovo è giunt'un

chavalier [2:31]

two-part madrigal · Jacopo da BOLOGNA (fl.1335-1355) |

British Museum, MS Add 29987

voices 1 2, lute, fiddle

7. Seguendo 'l canto [3:03]

two-part madrigal · Donato da FIRENZE (fl.1335-1375) |

Firenze, Bibl. Naz., MS 26 Panciatichi

voices 1 2, lute, fiddle

8. Pange melos [3:07]

conductus · Anonymous French, 13th c. |

Firenze, Biblioteca Laurenziana, MS Pluteus 29.4

voices 1 2, rebec, fiddle, percussion 3

9. Non al so amante [2:05]

Anonymous Italian, 14th cent. |

Faenza, Biblioteca Comunale, Cod. 117

gothic harp, lute, recorder 4

III. Fisi • Visiones

I saw a swete semly syght

a blisful birde, a blossum bright

that murnyng made & mirth of-mange

Anonimo inglese

10. Salve Regina [2:55]

antiphon · Guy of CHERLIEU (12th c.) |

Antiphonale Romanum

voices 1 2 3 4

11. Ave maris stella [1:38]

Anonymous Italian, 15th c. | Faenza, Biblioteca Comunale, Cod. 117

voices 1 2, lute

12. Ave mutter Koniginne ~ Ave mater [2:58]

three-part contrafactum ·

Oswald von WOLKENSTEIN (1377-1457) |

Innsbruck, Wolkensteinhandschrift B

voices 1 2, gothic harp, medieval harp 3, fiddle, percussion 2

13. Magdalena degna da laudare [3:07]

accompanied monodic lauda · Italian, 13th c. |

Laudario di Cortona

voices 1 2, gothic harp, medieval harp 2, recorder 4, percussion 3

14. Sancta mater gracie ~ Do way Robin [1:42]

two-part motet · English, 14th c. |

British Museum, MS Cotton Fragments XXIX

voices 1 2, medieval harp 1, rebec, fiddle, lute

15. Sainte Marie viergene [3:01]

accompanied monody · Saint Godric of FINCHALE (1080-1170) |

British Museum, MS Royal 5F

voice 2, medieval harp 1, recorder 4

IV. Banflaith • Regalitas

Ni raba-sa riam cen fer

ar scath araile ocum

Tain Bo Cuailnge, 15th c.

16. Quene note [3:00]

instrumental piece · FRANKES (English, 15th c.) |

Bodleian Library, MS Ashmole 191

gothic harp, rebec, lute, recorder 4, percussion 5

arranged by Doron Sherwin

17. Nobilis humilis [3:11]

discant / discantus in festo Sancti Magni

· Orkney Islands, 12th c. |

Uppsala, Univ. Lib., Codex 223

voices 1 2 3 4, recorders 1 2 4

18. Ave rex gentis anglorum [0:58]

antiphona in festo Sancti Eadmundi · Anonymous English, 10th c. |

Antiphonale Sarisburiense

voice 2

19. Deus tuorum ~ De flore marthyrum ~ Ave rex [1:29]

three-part motet · Anonymous English, 10th c. |

Bodleian Lib., MS E museo 7

voices 1 2, lute, fiddle

20. A l'entrada del tens clar [2:13]

accompanied monody · Anonymous Provençal, 12th c. |

Paris, Bibl. Nat., MS fr. 20050

voices 1 2 3, medieval harp, rebec, recorder 4, percussion 5

[ N. E. – La mayor parte de estas obras volverían a grabarlas para Arcana

en Insula feminarum ]

La Reverdie

1 · Ella de' Mircovich · voice, medieval harp, gothic

harp, recorder, percussion

2 · Elisabetta de' Mircovich · voice, rebec, medieval

harp, recorder, percussion

3 · Claudia Caffagni · lute, voice, medieval

harp, percussion

4 · Livia Caffagni · recorder, fiddle, voice

with the collaboration of

5 · Doron David Sherwin · percussion

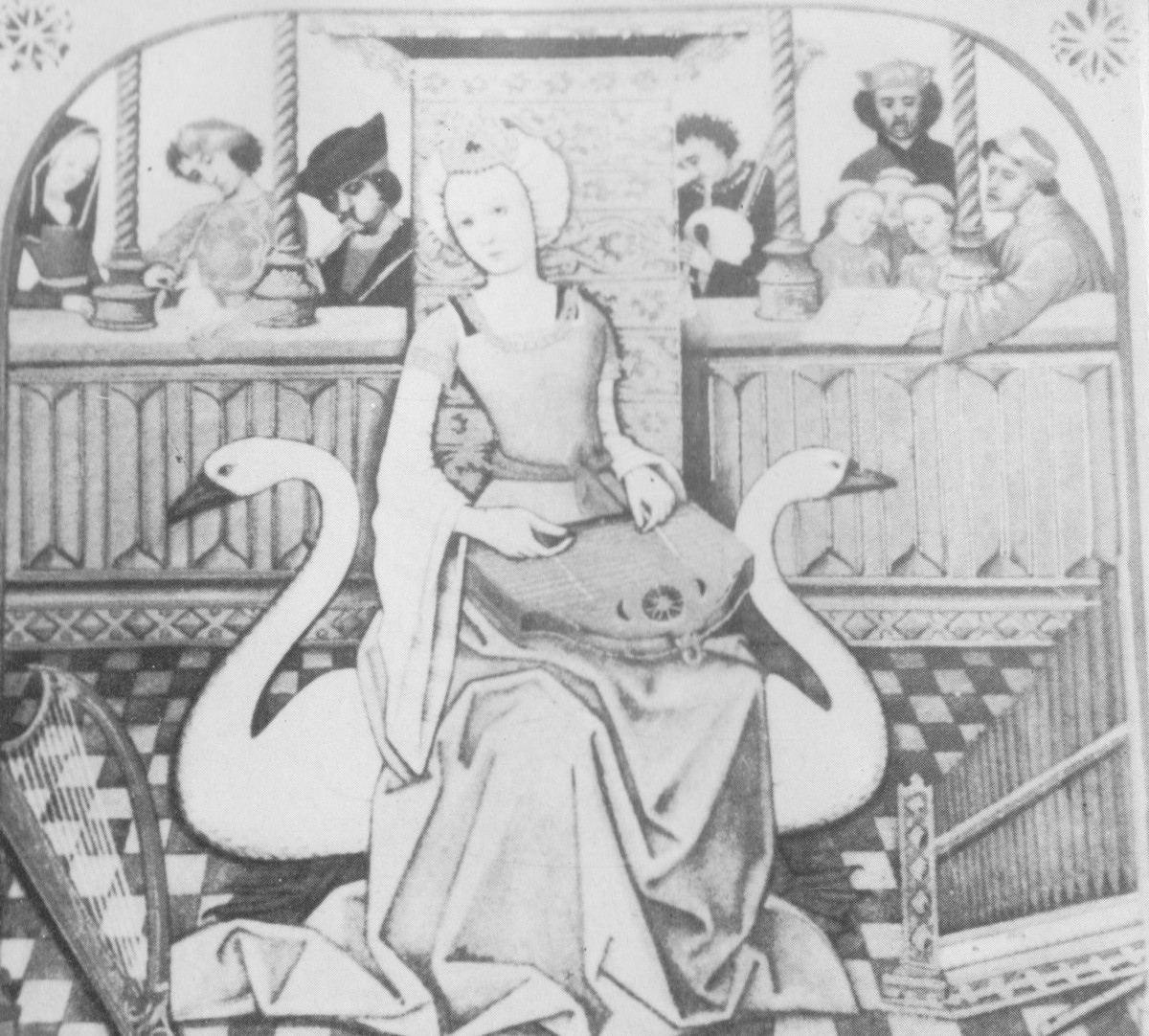

THE INSTRUMENTS

Lute – I. Magherini, Roma, 1988

Medieval harp – P. Zerbinatti, S. Marco di Mereto di Tomba, 1988

Gothic harp – P. Zerbinatti, S. Marco di Mereto di Tomba, 1989

Rebec – B. Tondo and R. Zerbinatti, Udine, 1987

Fiddle – S. Fadel, Valmadrera, 1989

C descant recorder – E. Delessert, Fribourg (CH), 1983

G treble recorder – A. Zaniol, Venezia, 1982

C tenor recorder – C. Collier, Berkeley (USA), 1984

Tabor – P. Williamson, Lincoln (GB), 1979

Bodran – A. Rota, Trichiana, 1991

Timbrel – A. Rota, Trichiana, 1991

Special thanks to Guerrino and Giovanni Cantoni for their kind

cooperation.

DDD

CD Code CS 201007

Production Andrea Seardtielli

Recording Producer Doron David Sherwin

Recording Villa Cantoni, Nonantola (Modena) 4/1991

Recording Engineer Roberto ChineIlato

Editing Gennaro Carone

Photo E. Fedrigoli

℗ 9 - 1991 Giulia International - Milano - Italy

© 1991 Ella de' Mircovich

Art Direction Xerios

Cover Design Giuseppe Spada

Made in Italy

GUINEVERE, YSEUT, MELUSINE

The heritage of Celtic womanhood in the Middle Ages

"Symbols, whether they be myths or ceremonies or objects, reveal their

full significance only within a particular tradition; one must be part

and parcel of that tradition to experience fully the power and

illumination of the myth. Such participation in the old Celtic

tradition is no longer possible".

In 1961, two British scholars Alwyn and Brinley Rees, expressed this

(apparently discouraging) conclusion as a preface to their seminal

essay "Celtic Heritage": nonetheless the work itself developed a

complex and penetrating comparative analysis of the philosophical,

social and mythical-religious bases of the Celtic civilisation and its

descendants through the centuries; an analysis which underlined its

many points of contact with the Indo-European cultural sphere (the same

points that Georges Dumézil has so minutely observed in many

studies), while at the same time pointing out its fundamental,

idiosyncratic characteristics.

Thirty years have passed since the appearance of "Celtic Heritage" and

rivers of ink have flowed on the subject of these analyses of the

Celtic heritage in Europe. Unhappily we have to concede that along with

the many works of unquestionable scientific accuracy, countless Volumes

have appeared by authors who clearly had no time for the wise, modest

admission of the limits inherent in this sort of analysis significantly

used by the Rees to introduce their work.

Given this plethora of "follies" (some indeed quite attractive, as the

great editorial popularity still enjoyed by the creations of such

pseudo Celtic scholars or "Celtomaniacs" demonstrates) it is with

extreme caution that we offer this collection of musical and textual

testimonies of the Celtic Heritage, within a subject that is as thorny

and controversial as the concept of "Femininity in Celtic thought" and

in its - late and fragmentary but unquestionable - Medieval vestiges.

We shall not touch upon sociological ramifications: the subjects we

will broach in this brief musical itinerary are all circumscribed

within a purely ideological and symbolic field. When we refer to the

concept of the "Dispenser of Regality" and of her incarnations, in myth

and at times in history, we will not be implying ideas of royal

matriarchy, and when we mention the dominant role of Woman in the

semi-legal case histories of Courtly Love, we shall not by any means be

postulating feminism avant la lettre.

Celtic society was fundamentally patriarchal (as was without a shadow

of a doubt all of European medieval society). All Indo-European

societies were patriarchal; but it is clear that within the group the

range of varying tendencies, more or less markedly patriarchal, was

considerable. Thus alongside societies in which the role of woman was

clearly subordinate and secondary (Latin, Greek) we find others in

which the feminine function was, at least ideally, much more elevated

and dignified (Germanic, Vedic and, to a greater extent, Celtic

society). Obviously there are no precise data concerning the real

social impact on the Celtic world of this particular feature, but what

does emerge incontrovertibly in mythology, in epics and in customs of

matrilinear succession is the fact that woman was considered to be a

being who was gifted with potent spiritual and material "energy" (an

anthropologist would call it "mana") which she alone, in particular

ways, could transmit to the male. If, as seems to be accepted, purely

linguistic customs are the expression of the particular mentality and

of the system of values of the society which produces them, then it

will be worth remembering that in the Celtic and Germanic languages the

genders of the Sun and the Moon are still to this day the opposite of

Romance languages. Beneath the level of language there lies mythical

ideology: the active, original principal, giver of light and strength

is feminine: the passive, cyclical, cold and vulnerable element is

masculine. This is the same Woman-Man model, practically a Celtic

prototype of the legend that was to spread throughout medieval Europe:

Tristan and Isolde have their immediate precursors in the characters of

an Irish myth, Diarmaid and Grainné. Grainné, the blond,

strong-willed heroine, has a name which tells its own story, meaning

literally "Sun" in Irish. Tristan, successor to the handsome hunter

Diarmaid, Tristan who without Isolde has neither the strength nor the

will to live, has a name which seems to be derived from the Pictish

"Dru-stanos", "Strength-from-fire", very simply, he who draws life from

the source of all fire and heat: the Sun (Grainné/Isolde).

And now that Tristan and Isolde have brought us out of the classical

Celtic into a medieval context, how could we fail to call to mind the

Lady and her role as a genuine feudal lord in skirts in that complex

and subtle game of Courtly Love? The Lady we meet in Courtly Love was,

in truth, quite different from her counterpart in real life. Women who

had no say at all in the actual exercise of power (with some notable

exceptions, to which we shall make reference later) saw themselves, in

the mystic/amorous theories fashionable in their "drawing rooms",

invested with the power of life and death over men, and by men they

were sung and acclaimed as the source and kindling spark of all wisdom

and all virtues, both martial and others - Mistresses, Initiators, as

were the queens, goddesses and female warriors of Celtic myths.

There has been no lack of discussion of this "Courtly Love". The

appellation "Courtly Love", or "Troubadour Love" (or Stilnovo or

Provençal Love) is in itself insufficient to account for a vast

and many-sided phenomenon which made its first appearance in the

aristocratic circles of 12th century Languedoc, then spread all over

Europe and wafted through European Christendom for centuries. In the

search for the most distant roots of this phenomenon even the most

abyssal depths have been sounded (Classical antiquity, the world of

Islam, even coeval Indian tantrism), often without our noticing that

its germ cells were far less exotic and arcane; they were lying under a

thin layer of centuries, in the Celtic, pagan past of France (and of

all those vast areas of Europe where Courtly Love was swiftly to take

root), not least Italy where the north door of the cathedral of Modena

conserves the oldest testimony of the diffusion of Arthurian legends

beyond the British Isles), the past whose repertory of myths and rites

had never become wholly foreign to the rural and peripheral levels of

society that were less susceptible to the succession of religious and

cultural movements. This repertory, that had lain dormant but not dead,

rose to the surface again in élite circles thanks to a series of

favourable historical coincidences and ideological conditions, and its

reappearance took the form that was as typical of élite circles

then as it is today: that of a literary and cultural "fashion". Within

less than a century in all Europe, from Italy to Iceland, from Germany

to Spain, there was a rage for romances, lays, songs on "Breton"

material, in other words narrations of certain Celtic derivation and

setting, based essenttially (but not exclusively) on Arthur and his

court. In all these stories, as in the much older and typically Irish

"Ulster" and "Fenian" cycles, the fundamental structure was always the

same: the King (who rather than an active, offensive force, represents

a sort of principle of equilibrium, an unmoving motor without which

chaos would gain the upper hand), the Queen (who is the real "provoker",

inspirer of the warlike exploits of the king's entourage, and who

- through the use of adultery which in medieval Europe had already lost

its ritual, hieratical status - "redistributed" the energy of which she

was the depositary, an energy which the successful functioning of court

and society could not and must not allow to be the exclusive attribute

of the King), and the Knights (who are in a sense the material

executors of the royal power, and who are all, if not lovers at least

servants of the Queen in the widest, most complete sense). Unlike

Tristan and Isolde, it is not clear who the direct Celtic forebears of

the couple Arthur-Guinevere were: Arthur (Artorios) is vaguely

reminiscent of a more or less historical Celtic sovereign, who for a

time was the champion of Britannic resistance to the Angle and Saxon

invaders. His name first appears in the ninth century in the somewhat

suspect "Historia Brittonum" by Nennius, an author who ingenuously

describes himself: "coacervavi omne quod inveni" [I have collected all

that I have discovered]; it is also worth remembering that the name

Arcturus, Artorios is etymologically closely related to the Celtic

goddess whose name appears on many Gallo-Roman stelae - Arctia, the

Goddess of the Bear. As for Guinevere, her name is simply a

"continental" version of "Findabair", who in Irish myths is the

daughter of queen Medb, possesssion of whom automatically conferred

sovereignty. What is less easy to explain in this Courtly-Arthurian

fashion is not then the source of inspiration (clearly rooted in their

Celtic humus) but the reasons for its rapid and lasting success.

Obviously every historical and cultural phenomenon possesses a series

of causes and coincidences, many of which elude our understanding: but

it is certain that this "Celtic Renaissance" of the twelfth century

(which left its mark on the literature and art of so many later

centuries) coincided with the meteoric rise of the so-called "Angevin

Empire".

It is a harmonious coincidence, for this was an "Empire" that was at

least partially founded on the "free choice" (in perfect Celtic style)

of a particularly strong-willed queen: Eleanor of Aquitaine,

granddaughter of the first troubadour, who divorced Louis VII of France

to marry Henry II of England and Normandy.

Eleanor, the unchallenged arbiter of European fashion and culture, was

the founder of those "Courts of Love", which more than any other,

thanks to her patronage of troubadours, men of letters, historians and

artists of all kinds, promoted the diffusion of the courtly ethos and

of the Breton romances that were imbued by this spirit. Undeniably

there is a sort of mysterious consistency in the fact that the role of

first "setter" of this fashion should have belonged to a woman. We

should not however overlook the fact that Eleanor's husband, Henry (who

was anything but a "passive" king of Celtic tradition) had sound

reasons to support this "Celtic Renaissance": having just accomplished

the conquest of a turbulent Ireland, this offered him excellent

propaganda, allowing him to insist with his new, recalcitrant subjects

on the ideal bond linking him to the Celtic past of Britain.

This fashion was obviously expressed not only in literature and the

figurative arts, but also in music; it is through music (and texts)

that we will attempt in this collection to draw up a brief description,

divided into four themes typical of the "Celtic Renaissance" and of its

later echoes in the twelfth century (echoes which at times are

indistinguishable from the - albeit rare - authentic survivals of an

uninterrupted Celtic tradition):

1) COURTLY LOVE;

2) ADVENTURE (historical-romance, mythical-seasonal adventure and the characteristic "Quests" of Celtic origin);

3) THE CULT OF THE VIRGIN, QUEEN AND MOTHER (which enjoyed a remarkable boom together with the triumph of the Courtly ethos);

4) THE PARTICULAR ROLE OF THE QUEEN (or rather, of the depositary of Regality).

We have decided to remain within a purely Celtic context, both in the

titles of the four sections (which follow some of the

"primscéla" or "literary genres" that the rules required to be

part of the repertory of "filidh" - official bards - of High Medieval

Ireland) and in the programme as a whole, which we have chosen to place

under the aegis of a Triad (ancient Welsh authors produced lists of

triads of characters, mythical or simply illustrious, and many gods and

especially goddesses appeared in the Celtic pantheon in a triple

aspect). We have conceived "our" Triad as a representation, from a

female point of view, of the three canonical divisions of Indo-European

societies as a whole, faithfully reproduced in the medieval pattern: Oratores / Bellatores / Laboratores.

The first function, the function of the Sacred and the Regal, is

personified by Guinevere; the second, the Warrior function, by Isolde

(who in the courtly legend is clearly polarized towards an exponent of

the second function - Tristan - to the detriment of an exponent of the

first - King Mark - just as Grainné abandoned Finn, chief of the

fiana and eloped with his "subaltern" Diarmaid). The third, material

prosperity, fertility, is represented by Melusina, the mythical

snake-woman (whose name, a corruption of "Mala Lucina", "Juno - or

Diana, the Ill-omened", reveals connections with the great archetypal

goddesses of whom we can never state with certainty whether they belong

to the Indo-European tradition or to its pre-Indo-European substrata),

prolific founder of the Lusignano dynasty and creatress of their

economic success.

We have decided to remain within a purely Celtic context, both in the

titles of the four sections (which follow some of the

"primscéla" or "literary genres" that the rules required to be

part of the repertory of "filidh" - official bards - of High Medieval

Ireland) and in the programme as a whole, which we have chosen to place

under the aegis of a Triad (ancient Welsh authors produced lists of

triads of characters, mythical or simply illustrious, and many gods and

especially goddesses appeared in the Celtic pantheon in a triple

aspect). We have conceived "our" Triad as a representation, from a

female point of view, of the three canonical divisions of Indo-European

societies as a whole, faithfully reproduced in the medieval pattern: Oratores / Bellatores / Laboratores.

The first function, the function of the Sacred and the Regal, is

personified by Guinevere; the second, the Warrior function, by Isolde

(who in the courtly legend is clearly polarized towards an exponent of

the second function - Tristan - to the detriment of an exponent of the

first - King Mark - just as Grainné abandoned Finn, chief of the

fiana and eloped with his "subaltern" Diarmaid). The third, material

prosperity, fertility, is represented by Melusina, the mythical

snake-woman (whose name, a corruption of "Mala Lucina", "Juno - or

Diana, the Ill-omened", reveals connections with the great archetypal

goddesses of whom we can never state with certainty whether they belong

to the Indo-European tradition or to its pre-Indo-European substrata),

prolific founder of the Lusignano dynasty and creatress of their

economic success.

We opened our brief discussion with the prudent observation made by the

Rees, that it will never be possible to recuperate, or "restore", a

myth or a symbolic concept of the past such that it can be completely

and entirely deciphered; we agree wholeheartedly with this statement.

Nonetheless, through the "restoration" of the countless fragments that

have survived to our day, we can glean an idea - however mutilated and

vague it may be - of that mysterious object which was the Celtic

concept of Femininity; that Celtic Femininity that the Breton scholar

Jean Markale scrutinised, perhaps even too passionately, in a work

which we would recommend to all those who are interested in "digging

deeper" after reading this summary excursus: "La Femme Celte", of 1972,

from which we have taken this quotation that seems to us to offer a

suitable epilogue, counter-balancing and complementing the sentence of

the Reeses with which we opened our discussion: "Nothing is more

tenacious than traditions, nothing more difficult to eradicate than

ancient beliefs, and ancient ways of thinking when they are camouflaged

under new forms. Myths never die: they return over and again in

different, new shapes, and at times we are astonished to discover them

where we would least expect to find them".

Section I: All the pieces in

the section dedicated to "Love" are expressions of the most typical

common themes of Courtly Love - spread over three centuries. Beside a

number of standardised texts (Pucelete bele / Je langui / La bionda trezza), there are others again that are doubly linked to the Celtic "leitmotif" of the collection: Tristan's Lament and the virelay Se Geneive, Tristan are clearly part of the area of "Breton material".

Section II: The recurrent

features of the "Adventure" of Celtic tradition - which were the source

of inspiration for the vast majority of courtly romances - might be

reduced in schematic fashion to three: the Quest (for a Person, or an

Object of capital importance), the Visit to or from the Other World (in

which a supernatural Lady or King comes from the Beyond to carry off a

mortal with whom he or she has fallen in love); and the Contest of the

Seasons (where the material is generally that of the young champion of

Spring, of Rebirth - who at times is also personified by a maid - who

opposes and overcomes the failing powers of Winter). In this category

we can of course include Di novo è giunt'un chavalier with its Winter Knight mounted on a horse shod with ice, and the "Lady of Heat" who will defeat him. Seguendo 'l chanto

also belongs to the second section: here the Lady from the Other World,

the Goddess, is defined - with a procedure of mythical equivalencies

that had already been used in Caesar's "De Bello Gallico" - as Diana.

Like so many Dianas of courtly legend, she shares with the Great

Goddesses of Irish and Welsh Celtic tradition the Bird of Augury, the

mystic Apple Tree (the same tree that gives its name to the Happy Isle

of Celtic tradition, Avalon) and their polymorphous, warriorlike

appearance. The subject of the Quest appears in Ja nus hons pris

(whose author, Richard Coeur de Lion, was in fact none other than the

favourite son of an old acquaintance of ours, Eleanor of Aquitaine)

which had already inspired in the thirteenth century the charming

legend which relates that Blondel de Nesle, Richard's court musician,

set off in search of his imprisoned lord, and succeeded in finding him

"by ear", hearing him sing this melancholy prison song one day in the

tower where he was confined. The set is completed by two compositions,

this time indirectly connected to the theme of "Adventure": two typical

examples of the lament (the Irish "caoine", integral part both of the

millenary epic culture and of popular custom), a genre which, although

it may not belong exclusively to the "echtrai" in the strict sense of

the word, is still a part of our basic theme, belonging to that sphere

of influence which is clearly and almost exclusively female. The finest

"caoine" of the Celtic epic are always sung by heroines, be they

Deirdriu, Grainné or Emer, mythical prototypes of the Gaelic

hired mourners who still perform this function in a few islands off the

coast of southern Ireland. As in our Pange melos

these laments almost always use the purely Celtic rhetoric expedient of

the so-called "pathetic fallacy", in which all of nature is made to

participate actively in the display of mourning.

Section III: the rise of the

courtly ethos coincides with a prodigious expansion of the cult of Mary

and the foundation of the great sanctuaries dedicated to the Blessed

Virgin (which, it has been remarked, often arose on sites which had

formerly been consacrated to the cult of Celtic goddesses). With one

exception, all the pieces in this section concern the Virgin,

particularly in the role (swiftly bestowed by Celtic peoples who

retained vague memories of the role occupied in their Pantheon of

Goddesses, and later assumed by the semi-divine Queens of their

mythology) of Queen, Mother and at the same time Wife of the King, at

whose side her function was that of Mediator and of indispensable

helper in the process of salvation. The exception is Magdalena degna da laudare,

the song in praise of Mary Magdalen, whose typical attributes (the vase

and long, flowing hair) made her easy to associate with the long-haired

fertility goddesses who survived for so long in the collective European

imagery, camouflaged in the ranks of Christian saints. As the German

scholar Jutta Stroeter-Bender has so accurately demonstrated, Mary

Magdalen shared this destiny with mainy saints, including Barbara and

Catherine with their suggestive attributes, the tower and the wheel.

Section IV: "Banflaith" in

Irish indicates both an abstract concept, "Regality", and a mythical

character: the splendid ultramundane Lady, whose kiss, the "friendship"

of whose loins or general attentions, were capable of raising a mortal

man to the status of a King, of a bridge to the supernatural. This

fundamental Celtic concept (the same concept according to which in

myths Queens, tangible personifications of the Banflaith, were placed

on a higher plane than their husbands, and Kings were kings inasmuch as

they were husbands, real or mystical, of a Goddess who, whether or not

she was incarnated as a flesh and blood queen, was the real mistress of

the realm) produced an interesting phenomenon in the High Middle Ages,

exclusively in those areas where the particular Germanic ideology of

regality blended with its Celtic equivalent: the concept of Virgin

Kings - virgins presumably in the sense that they were traditionally

mystic consorts of the ancient Goddess, or rather because they were

jealously possessed by that abstract, philosophical personification of

the Banflaith. Canonised by a clergy which, as in the Anglo-Saxon and

Irish world, continued to see the sovereign as physically and totally

responsible for the well-being of his realm, they enjoyed a flourishing

cult which survived in Northern Europe until the late fifteenth

century. Two particularly striking examples are presented in this

context: the case of Saint Magnus Erlendsson, Jarl of the Orkneys in

his lifetime and their patron saint after his untimely death at the

hands of his cousin Hakon Palsson (Nobilis Humilis Magne) and again St. Edmund, last king of East Anglia and patron saint of England (Ave Rex gentis, Deus tuorum militum / De flore martyrum)

whose hagiography - as is quite transparent in the texts of the pieces

- overflows with mythical topoi of Germano-Celtic derivation; from the

"multiple death" during the sacrifical period of "Samain" (November)

shared with so many Kings in Irish myth, to the ravens and grey wolves

who watch over him just as the ravens of Badb, Goddess of War, and the

magic horse Liath Macha, the grey horse of Macha watch over the corpse

of the hero Cachulainn, and again the purely Celtic prodigy, which is

also to be found in the version of the "Passio Sancti Eadmundi" by the

sobre Anglo-Saxon bishop Aelfric, of the severed head that speaks. The

collection finishes with one of the most famous musical versions of the

Celtic Triangle: A l'entrada del tens clar,

whose "queen, Flower of April", who prefers a "leugier bachalar" is

quite simply a rather affected, distant descendant of that long line of

prototypes of Femininity, which we have encountered along this tortuous

path through the remnants of Celtic myths, running from the Great

Goddesses, by way of the warlike, semi-divine Queens such as Medb and

Rhiannon to those delight fully worldly queens such as Guinevere in

courtly romances.

Ella de' Mircovich

LA REVERDIE

In the panorama of medieval music La Reverdie

is in many senses an atypical group: from its composition (four

sisters, who are at one and the same time singers and instrumentalists)

to its name (no serious titles lifted from treatises, no references to

revered authours and no Latin but a term in the vernacular which

recalls the spring, green, renewal, and the melodies which celebrated

all these things in the Middle Ages).

La Reverdie prefers to orient

itself towards a secular repertoire, with brief incursions into "minor"

sacred music: the four members of the ensemble feel that they are

essentially heirs, not so much of professional minstrels or components

of the ecclesiastical scholae

as of those small circles of amateur performers who made music for

their own delight and for the entertainment of their neighbours in

noble courts and in the homes of the upper bourgeoisie.

GINEVRA, ISOTTA, MELUSINA

I retaggi della femminilità celtica nel Medioevo europeo

"I simboli - si tratti di miti, di cerimonie o di oggetti - rivelano

appieno il loro significato solo nel contesto di una determinata

tradizione: si deve far parte integrante di quella tradizione per

sperimentare il mito in tutto il suo potere d'illuminazione: e una

simile partecipazione all'antica tradizione celtica è ormai

impossibile".

Nel 1961, i due studiosi britannici Alwyn e Brinley Rees formulavano

questa - apparentemente scoraggiante - premessa al loro fondamentale

saggio "Celtic Heritage": ciò malgrado, il prosieguo dell'opera

impostava e sviluppava una complessa ed acuta analisi comparativa delle

basi filosofiche, sociali e mitico-religiose della civiltà

celtica e delle sue propaggini attraverso i secoli; analisi che

sottolineava tanto i suoi molti punti di contatto col complesso

culturale indoeuropeo (quegli stessi punti di contatto che Georges

Dumézil ha esaurientemente sviscerato in tanti studi), quanto le

sue fondamentali, caratteristiche idiosincrasie.

Nei trent'anni che ci separano dall'uscita di "Celtic Heritage" fiumi

d'inchiostro sono stati versati nell'ambito di queste analisi del

Retaggio Celtico di Europa; e bisogna purtroppo ammettere che, accanto

a lavori d'indubbio rigore scientifico, sono comparsi innumerevoli

volumi dovuti ad autori cui, palesemente, non garbava affatto tener

presente quella saggia e modesta ammissione dei limiti insiti in una

simile analisi con la quale i Rees avevano significativamente

inaugurato il loro libro.

Proprio a causa di questa mole di "imprudenze" (talvolta, peraltro,

assai accattivanti, come dimostra la vasta popolarità editoriale

di cui hanno goduto, e godono tuttora, questa parte di pseudo-celtisti,

o piuttosto celtomani) è con estrema cautela che proponiamo

questa raccolta di testimonianze musicali e testuali del Retaggio

Celtico, ed all'interno di un tema così spinoso e dibattuto come

quello del concetto di "Femminilità nel pensiero celtico" e

nelle sue - tarde e frammentarie, ma incontestabili - vestigia

medievali.

Non ci addentreremo quindi in applicazioni "sociologiche": i terni che

sfioreremo, in questo breve itinerario musicale, si situano tutti in un

ambito puramente ideologico e simbolico. Quando accenneremo al concetto

della "dispensatrice di Regalità" e delle sue incarnazioni, nel

mito e talvolta nella Storia, non implicheremo assolutamente idee di

matriarcato reale; quando menzioneremo il ruolo dominante della Donna

nella casistica semi-legale dell'Amor Cortese non postuleremo affatto

femminismi ante-litteram.

La società celtica era (così come lo era, senza ombra di

dubbio, la società europea medievale nella sua totalità)

basilarmente patriarcale. Tutte le società indoeuropee lo erano;

ma è indubbio che nel loro ambito la gamma degli orientamenti

più o meno spiccatamente patriarcali era piuttosto ampia. E'

così che, accanto a società nelle quali il ruolo della

donna era nettamente subordinato e secondario (la latina, la greca), ne

troviamo altre in cui la funzione femminile era, almeno idealmente,

assai più elevata e dignitosa (la germanica, la vedica, e, in

misura ancora maggiore, la celtica). Non abbiamo ovviamente dati

precisi riguardo all'effettivo impatto sociale di questa

particolarità nel mondo celtico, ma ciò che

incontrovertibilmente traspare dalla mitologia, dall'epica e dalle

consuetudini di successioni matrilineari, è che la donna era

considerata un essere dotato di una potentissima "energia" ("mana",

direbbe un antropologo) spirituale e materiale, che lei sola poteva,

tramite determinati canali, trasmettere al maschio.

Se, come pare accettato, le consuetudini puramente linguistiche sono

l'espressione della particolare forma mentis, della struttura di valori

della società che le produce, gioverà allora rammentare

qui che tuttora, nelle lingue celtiche e germaniche, i generi del Sole

e della Luna sono invertiti rispetto alle lingue romanze. Al di sotto

del linguaggio traspare l'ideologia mitica: il principio attivo,

perenne, datore di luce e di forza, è femminile: quello passivo,

ciclico, gelido e vulnerabile, è maschile. Si tratta del

medesimo schema Donna-Uomo sotteso al prototipo celtico di una leggenda

che godrà, nel Medioevo europeo, d'enorme diffusione: Tristano e

Isotta hanno i loro immediati precursori nei due protagonisti di un

mito irlandese; Diarmaid e Grainné. Grainné, la bionda e

volitiva eroina, porta un nome che parla da sé e che, in

irlandese, significa letteralmente "Sole"; Tristano, l'epigono del bel

cacciatore Diarmaid, Tristano che privo d'Isotta non ha materialtnente

né la forza nè la voglia di vivere, ha un nome che

(razionalizzazioni etimologiche medievali a parte) pare derivare dal

pittico "Dru-stanos", "Forza-dal-Fuoco": in parole povere, colui che

trae la vita dalla fonte di ogni fuoco e di ogni calore: il Sole

(Grainné/Isotta).

E già che ormai, con Tristano e Isotta, ci troviamo in ambiente

medievale e non più celtico classico, come non richiamare alla

mente la Dama ed il suo ruolo di vero e proprio signore feudale in

gonnella entro quel complesso e raffinato gioco intellettuale che

è l'Amor Cortese? La Dama dell'Amor Cortese era, in

verità, assai differente dalla sua collega della vita reale:

donne che nell'esercizio effettivo del potere non contavano nulla

(tranne alcune notevoli eccezioni confermanti la regola, alla quale

accenneremo in seguito) si trovavano insignite, nelle teorie

mistico-amorose in voga nei loro "salotti", di potestà di vita e

di morte sugli uomini, e dagli uomini erano cantate e riconosciute come

fonti e suscitatrici d'ogni sapienza e d'ogni virtù, marziale e

non - Padrone, ed Iniziatrici, proprio come le regi- ne, le dee e le

guerriere dei miti celtici.

Si è assai discusso sulle origini di questo "Amor Cortese".

L'appellativo stesso di Amor Cortese, o Amor Trobadorico (o

Stilnovista, o Provenzale) di per sé insufficiente a render

conto di un fenomeno vastissimo e pieno di sfaccettature, che fece si

la sua prima comparsa negli ambienti aristocratici occitani del

Dodicesimo secolo, ma si estese poi a macchia d'olio, ed aleggiò

per secoli su tutto l'Occidente cristiano. Per scovare le radici

più remote di questo fenomeno si è andati a scavare a

profondità talvolta abissali (l'Antichità Classica, il

mondo islamico, perfino il coevo tantrismo indiano), spesso senza

accorgersi che le cellule germinali erano infinitamente meno esotiche

ed arcane: e giacevano sepolte, ricoperte da un sottile deposito di

secoli, nel passato celtico e pagano della Francia (e di tutte quelle

vaste zone d'Europa ove l' Amor Cortese attecchì prontamente;

non ultima l'Italia, che sul portale nord del Duomo di Modena conserva

la più antica testimonianza della diffusione delle leggende

arturiane al di fuori delle Isole Britanniche), quel passato il cui

repertorio di miti e riti non era mai divenuto del tutto estraneo agli

strati rurali o periferici della società europea, meno

influenzati dalle successive correnti religiose e culturali. Questo

repertorio, sonnecchiante, non morto, torno a galla nei circoli

d'élite per una serie di coincidenze storiche e di condizioni

ideologiche favorevoli; e tornò a galla in una veste

caratteristica dei circoli elitari, allora come oggi: quella della

"moda" culturale e letteraria.

Entro meno di un secolo in tutta l'Europa, dall'Italia all'Islanda,

dalla Germania alla Spagna, furoreggiarono i romanzi, i lai, le canzoni

di materia "bretone", ossia quelle narrazioni, di provenienza e di

ambientazione inequivocabilmente celtiche, incentrate soprattutto (ma

non esclusivamente) su Artù e sulla sua corte. Ed in queste

storie, così come in quelle, ben più arcaiche e

tipicamente irlandesi, del Ciclo "dell'Ulster" e di quello "Feniano",

la struttura di base rimaneva la stessa: il Re (che più che una

forza attiva, offensiva, incarna una sorta di principio equilibratore,

di motore immobile senza il quale il caos prenderebbe il sopravvento),

la Regina (che è la vera "provocatrice", ispiratrice, delle

imprese belliche dell'entourage del proprio consorte, e che - tramite

una pratica dell'adulterio che nel Medioevo europeo cristiano ha ormai

perso lo status rituale, ieratico, che le era stato proprio nella

tradizione celtica - "ridistribuisce" l'energia della quale è

depositaria, energia che per il buon funzionamento della corte e della

società non può e non deve rimanere appannaggio esclusivo

del Re), e i Cavalieri (che sono delle specie di "esecutori materiali"

della potestà regale, e che sono tutti, se non addirittura

amanti, servitori della Regina nel senso più ampio e completo).

A differenza di Tristano e Isotta, non è chiaro quali siano gli

immediati "ascendenti" celtici della coppia Artù-Ginevra:

Artù (Artorios) conserva il vaghissimo ricordo di un più

o meno storico sovrano celtico che fu per qualche tempo campione della

resistenza britannica contro gli invasori angli e sassoni, ed il cui

nome compare per la prima volta nel Nono secolo, nel- l'alquanto

sospetta "Historia Brittonum" di Nennio, autore che si descrive

ingenuamente da sé: "coacervavi omne quad inveni"; giova anche

rammentare che il nome Arcturus, Artorios, etimologicamente

strettamente legato a quella dea celtica il cui appellativo compare su

tante steli gallo-romane - Arctia, la Dea dall'Orso. Quanto a Ginevra,

il suo nome non è altro che una versione "continentale" di

"Findabair", che nei miti irlandesi è la figlia della regina

Medb, colei il cui possesso attribuiva automaticamente la

sovranità. Quel che appare poco spiegabile di questa moda

cortese-arturiana, non sono dunque tanto le radici ispirative

(chiaramente abbarbicate al loro humus celtico) quanta i motivi di un

così rapido e duraturo successo. E' ovvio che, come in tutti i

fenomeni storici e culturali, vi fu un coacervo di cause, di

coincidenze, delle quali molte sfuggono alla nostra comprensione: ma

certamente questo "Rinascimento Celtico" del Dodicesimo secolo (che

dette un'impronta caratteristica alla letteratura ed all'arte di tanti

secoli successivi) coincise con il periodo della folgorante ascesa del

cosiddetto "Impero Angioino".

E, coincidenza armoniosa, si trattò di un "Impero" costituitosi

in parte grazie alla "libera scelta" (in perfetto stile celtico) di una

regina particolarmente volitiva: quella Aliénor d'Aquitania,

nipote del primo trovatore, che divorziò da Luigi Settimo di

Francia per sposare Enrico d'Inghilterra e Normandia. Fu proprio lei,

arbitra incontrastata della moda e della cultura europee, istitutrice

delle famose "Corti d'Amore", che più di chiunque altro, tramite

il suo patrocinio di trovatori, letterati, storici ed artisti d'ogni

sorta, promosse la diffusione dell'ideologia cortese, e dei romanzi

bretoni che di quell'ideologia erano imbevuti; e non si può

negare che vi sia una sorta di misteriosa coerenza nel fatto che il

ruolo primario nel "lancio" di questa moda fosse appannaggio proprio di

una donna. Tuttavia non bisogna trascurare il fatto che anche il marito

di Aliénor, Enrico (che non era certo un re "passivo" da

tradizione celtica), aveva tutte le ragioni di patrocinare questo

"Rinascimento Celtico": reduce dalla conquista dell'inquieta Irlanda,

era per lui ottima propaganda presso i suoi nuovi e recalcitranti

sudditi sottolineare il legame ideale che lo univa al passato celtico

della Britannia.

Ovviamente, questa moda trovò espressione, oltre che nella

letteratura e nelle arti figurative, anche nella musica: ed è

proprio attraverso la musica (ed i testi) di questa raccolta che

tenteremo di delinearne un breve quadro, articolato in quattro sezioni

dedicate ad alcuni temi tipici del "Rinascimento Celtico"` e dei suoi

echi posteriori al Dodicesimo secolo (echi che talvolta sono

indistinguibili dalle - sia pur rare - autentiche sopravvivenze di una

ininterrotta tradizione celtica):

1) L'AMOR CORTESE;

2) L'AVVENTURA (quella storico-romanzata, quella mitico-stagionale, e

la caratteristica "Queste", "Cerca" di ascendenza celtica);

3) IL CULTO DELLA VERGINE, REGINA E MADRE (che conobbe uno strepitoso

"boom" proprio in concomitanza col trionfo dell'ideologia cortese);

4) IL RUOLO PARTICOLARE DELLA REGINA (o, meglio detto, della Depositaria della Regalità).

E siamo voluti restare in ambito squisitamente celtico tanto per i

titoli delle quattro sezioni (che ricalcano alcuni dei

"primscéla", o "generi letterari" che dovevano per regolamento

aver posto nel repertorio dei "filidh" - bardi diplomati - dell'Irlanda

altomedievale), quanta per quello del programma nella sua

totalità, che abbiamo voluto porre sotto l'egida di una Triade

(gli antichi autori gallesi compilavano addirittura degli elenchi di

triadi di personaggi mitici o semplicemente illustri, e molti

déi - e soprattutto dee - del Pantheon celtico comparivano sotto

un triplice aspetto). La "nostra" Triade l'abbiamo inoltre concepita

come rappresentativa, (la un punto di vista femminile, delle tre

ripartizioni canoniche proprie alle società indoeuropee nel loro

complesso e fedelmente riprodotte nello schema

medievale Oratores/Bellatores/Laboratores: la Prima Funzione,

quella della Sacralità, della Regalità, è

naturalmente incarnata da Ginevra; la Seconda, quella Guerriera, da

Isotta (che nella leggenda cortese è chiaramente polarizzata

verso un esponente della Seconda Funzione - Tristano - a scapito di uno

della Prima - Re Marke -, così come la Grainné irlandese

abbandona Finn, capo dei fíana, per fuggire col suo "subalterno"

Diarmaid); la Terza, quella della Prosperità materiale, della

Fecondità, da Melusina, la mitica Donna-serpente (il cui nome,

corruzione di "Mala Lucina", "Giunone - o Diana, Infausta", tradisce i

suoi legami con quelle delle Grandi Dee archetipe di cui non si

può mai dire con certezza se appartengano alla tradizione

indoeuropea od ai suoi substrati preindoeuropei) prolifica capostipite

della dinastia dei Lusignano e creatrice della loro Fortuna economica.

E siamo voluti restare in ambito squisitamente celtico tanto per i

titoli delle quattro sezioni (che ricalcano alcuni dei

"primscéla", o "generi letterari" che dovevano per regolamento

aver posto nel repertorio dei "filidh" - bardi diplomati - dell'Irlanda

altomedievale), quanta per quello del programma nella sua

totalità, che abbiamo voluto porre sotto l'egida di una Triade

(gli antichi autori gallesi compilavano addirittura degli elenchi di

triadi di personaggi mitici o semplicemente illustri, e molti

déi - e soprattutto dee - del Pantheon celtico comparivano sotto

un triplice aspetto). La "nostra" Triade l'abbiamo inoltre concepita

come rappresentativa, (la un punto di vista femminile, delle tre

ripartizioni canoniche proprie alle società indoeuropee nel loro

complesso e fedelmente riprodotte nello schema

medievale Oratores/Bellatores/Laboratores: la Prima Funzione,

quella della Sacralità, della Regalità, è

naturalmente incarnata da Ginevra; la Seconda, quella Guerriera, da

Isotta (che nella leggenda cortese è chiaramente polarizzata

verso un esponente della Seconda Funzione - Tristano - a scapito di uno

della Prima - Re Marke -, così come la Grainné irlandese

abbandona Finn, capo dei fíana, per fuggire col suo "subalterno"

Diarmaid); la Terza, quella della Prosperità materiale, della

Fecondità, da Melusina, la mitica Donna-serpente (il cui nome,

corruzione di "Mala Lucina", "Giunone - o Diana, Infausta", tradisce i

suoi legami con quelle delle Grandi Dee archetipe di cui non si

può mai dire con certezza se appartengano alla tradizione

indoeuropea od ai suoi substrati preindoeuropei) prolifica capostipite

della dinastia dei Lusignano e creatrice della loro Fortuna economica.

Abbiamo voluto aprire questo breve discorso con la prudente

osservazione dei Rees, secondo i quali non sarà mai possibile

recuperare, "restaurare", un mito o un concetto simbolico del passato

in modo tale da decifrarlo completamente ed esaurientemen te; e su

ciò concordiamo perfettamente. Ciò non toglie,

però, che tramite il "restauro" degli innumerevoli frammenti che

sono giunti sino a noi, si possa ottenere un'idea- mutila e vaga quanta

si vuole, ma pur sempre una idea - di quell'oggetto misterioso che tu

il concetto celtico di Femminilità; quella Femminilità

Celtica che lo studioso bretone Jean Markale ha, forse fin troppo

appassionatamente, vivisezionato in un'opera che consigliamo a

chiunque, dopo questo sommario excursus, sia rimasta la voglia di

"scavare più a fondo": "La Femme Celte", del 1972, dal quale

traiamo questa citazione che ci pare pater fungere opportunamente da

epilogo, controbilanciando e completando la frase dei Rees con la quale

cominciammo: "Non v'è nulla di più tenace delle

tradizioni, di più difficilmente sradicabile delle antiche

credenze, degli antichi sistemi di pensiero allorchè si

mimetizzano sotto nuovi aspetti. I miti non muoiono mai: si

riattualizzano costantemente sotto forme nuove e differenti, ed

è talvolta stupefacente scoprirli là dove non ci si

sarebbe mai aspettati di trovarli".

Sezione I: Tutti i brani della

sezione dedicata agli "Amori" sono ovviamente espressioni - disperse

nell'arco di tre secoli - dei più tipici luoghi comuni dell'Amor

Cortese. Accanto ad alcuni testi assai standardizzati (Pucelete bele / Je langui, La bionda trezza), ve ne sono tuttavia altri doppiamente legati al "fil rouge" celtico della raccolta: il Lamento di Tristano e la virelai Se Geneive, Tristan si situano manifestamente nell'area della "materia bretone".

Sezione II: Le costanti deli'

"Avventura" di tradizione celtica - quelle che poi forniranno lo spunto

alla stragrande maggioranza dei romanzi cortesi - si potrebbero

schematicamente ridurre a tre: la Ricerca (di una Persona, o di un

Oggetto di capitale importanza), la Visita nello/dall'Aldilà (in

cui una Dama o un Re sovrannaturali vengono dall'Altro Mondo a rapire

od a chiamare a sè un mortale del quale si sono invaghiti) e la

Contesa Stagionale (in cui il tema rimane sostanzialmente sempre quello

del giovane campione della Primavera, della Rinascita che talvolta

incarnato da una fanciulla - che si oppone vittoriosamente alle

declinanti potenze dell'Inverno). A quest'ultima categoria è

naturalmente riconducibile Di novo è giunt'un chavalier

con il suo Cavaliere Inverno sul cavallo dai ferri di ghiaccio, e la

"Dama del Calore" sua debellatrice; nella seconda categoria si situa Seguendo'l chanto,

in cui la Dama dell'Altro Mondo, la Dea, definita - mediante un

procedimento di equivalenze mitiche già adottato da Cesare nel

"De Bello Gallico" - "Diana": ma come le tante "Diane" delle leggende

cortesi condivide con le Grandi Dee celtiche irlandesi e gallesi

l'Uccello Messaggero, il mistico Albero di Mele (quello stesso che

dà il nome all'Isola Felice della tradizione celtica, Avalon) e

l'aspetto polimorfo e guerriero. Al topos della Cerca si riallaccia

invece Ja nus hons pris (il

cui autore, Riccardo Cuor di Leone, non era del resto che il figlio

prediletto di una nostra vecchia conoscenza, Aliénor

d'Aquitania), che già nel Duecento aveva ispirato la graziosa

leggenda secondo la quale Blondel de Nesle, musico di corte di

Riccardo, partito alla ricerca del suo signore prigioniero, fu in grado

di ritrovarlo "ad orecchio" udendolo un giorno cantare, dalla torre in

cui era confinato, questo malinconico canto di prigionia. Completano il

quadro due composizioni in relazione stavolta indiretta con

l"Avventura": si tratta di due tipici esempi di compianto (il "caoine"

irlandese, parte integrante tanto della millenaria cultura epica quanto

delle consuetudini popolari), genere che, pur essendo "di casa" non

esclusivamente nelle "echtrai" propriamente dette, è in compenso

assai pertinente al nostro tema di base, rientrando in una sfera

d'influenza nettamente e quasi esclusivamente femminile. I più

bei "caoine" dell'epica celtica vengono sempre cantati dalle eroine,

siano esse Deirdriu, Grainné o Emer, mitici prototipi delle

prefiche gaeliche che tutt'oggi esercitano la loro funzione in poche

isolette dell'Irlanda meridionale; e quasi sempre (come nel caso del

nostro Pange melos) questi

compianti sfruttano l'espediente retorico, squisitamente celtico, della

cosiddetta "fallacia patetica": quello per cui l'intero mondo della

natura viene fatto partecipare attivamente alle manifestazioni di lutto.

Sezione III. La comparsa

dell'ideologia cortese coincise con una prodigiosa espansione del culto

mariano, e con la fondazione dei grandi santuari dedicati alla Madonna

(i quali, come è già stato fatto notare da più

parti, sorsero spesso su siti anticamente consacrati al culto di dee

celtiche). Tranne uno, tutti i brani di questa sezione concernono la

Vergine, soprattutto nel ruolo - che le popolazioni d'area celtica,

oscuramente memori del molo ricoperto nel loro arcaico Pantheon dalle

Dee, ed in seguito dalle Regine semidivinizzate del mito, le

assegnarono ben presto - di Regina, di Madre ed al tempo stesso Sposa

del Re, presso il quale la funzione di lei è quella,

squisitamente attiva, di Mediatrice, di indispensabile collaboratrice

nel progetto salvifico. L'unica eccezione è costituita dalla

lauda in onore di Maria Maddalena, la quale, per via dei suoi tipici

attributi (la lunghissima chioma ed il vaso), era facilmente

assimilabile a quelle dee chiomate della fertilità che

indugiarono lungamente nell'immaginario collettivo europeo, mimetizzate

fra la folla rutilante delle sante cristiane; sorte questa che, come ha

acutamente dimostrato la studiosa tedesca Jutta Stroeter-Bender,

la Maddalena condivide con inolte sante, fra cui Barbara e Caterina coi

loro sug- gestivi attributi, la Torre e la Ruota.

Sezione IV. "Banflaith" in

irlandese può indicare tanto un concetto astratto, "la

Regalità", quanto un personaggio mitico: la splendida Dama

ultraterrena il cui bacio, la cui "amicizia dell'anca" o le cui

attenzioni più generiche fanno si che un uomo mortale venga

automaticamente elevato al rango di Re, di ponte col sovrannaturale.

Questo fondamentale concetto celtico (lo stesso per il quale, nei miti,

le Regine, personificazioni tangibili della Banflaith, sono situate su

un piano differente rispetto ai loro mariti, ed i Re sono re in quanto

sposi, effettivi o mistici, di una Dea che - incarnata o meno in una

regina di carne ed ossa - è la vera signora del reame) produsse

nell'Alto Medioevo, ed esclusivamente in aree nelle quali la peculiare

ideologia germanica della regalità si mescolò al proprio

equivalente celtico, un interessante fenomeno, sino ad Oggi poco o

punto studiato: quello dei Re Vergini - vergini in quanto,

presumibilmente, consorti mistici per tradizione dell'antica Dea, o,

piuttosto, in quanto gelosamente posseduti da quell'astratta,

filosofica personificazione che è la Banflaith. Canonizzati da

un clero che, come quello anglosassone e irlandese, considerava tuttora

il sovrano come fisicamente visceralmente responsabile del benessere

materiale del regno, continuarono a godere nel Nord Europa di un

fiorente culto fino al tardo Quattrocento. In questa sezione sono

rappresentati due casi particolarmente eclatanti, quello di San Magnus

Erlendsson, jarl delle Orkneys in vita, e loro patrono dopo l'immatura

morte per manu del cugino Hakon Pálsson Nobilis humilis Magne, quello di Sant'Edmondo, ultimo re d'East Anglia Patrono d'Inghilterra Ave Rex gentis, Deus tuorum militum / De flore martyrum,

la cui agiografia - come del resto traspare sufficientemente anche dai

testi dei brani - trabocca di suggestivi topoi mitici d'ascendenza

germanico-celtica: dalla "morte multipla" durante il periodo

sacrificale del Samain (novembre) che lo accomuna a tanti Re dei miti

irlandesi; ai corvi ed al lupo grigio che vegliano su di lui

così come i corvi di Badb, Dea della guerra, ed il magico

cavallo Lìath Macha, il Grigio di Macha, vegliano sul corpo

dell'eroe Cúchulainn; al prodigio squisitamente celtico, e

riscontrabile persino nella versione della "Passio Sancti Eadmundi" del

sobrio vescovo anglosassone Aelfric, della testa mozza parlante. La

raccolta si conclude con una delle più celebri versioni musicali

del Triangolo Celtico: A l'entrada del tens clar,

la cui "regina Fior d'Aprile" che preferisce al vecchio re un "leugier

bachalar"- non è che l'ormai un po' leziosa, lontana discendente

di quella lunga serie di prototipi della Femminilità che, a

partire dalle Grandi Dee, passando per le bellicose Regine

semidivinizzate come Medb e Rhiannon e per quelle deliziosamente

terrene come la Ginevra dei romanzi cortesi, abbiamo incontrato durante

questo nostro tortuoso itinerario fra le macerie dei miti celtici.

Ella de' Mircovich

LA REVERDIE

Nel panorama della musica medioevale, la Reverdie

è un gruppo atipico sotto molti punti di vista: dall'organico

(quattro donne, cantanti e strumentiste al tempo stesso), al nome

(niente seri titoli di trattati, niente richiami a riveriti autori, e

niente latino, bensì un termine in volgare che richiama la

primavera, il verde, il rinnovamento, e le melodie che nel Medioevo li

celebravano). La Reverdie si orienta di preferenza verso un repertorio

profano, con brevi incursioni nella musica sacra "minore": le quattro

componenti si sentono in fondo eredi, piuttosto che dei menestrelli di

professione o delle scholae

ecclesiastiche, di quei piccoli circoli di amatori-esecutori che, nelle

corti nobiliari e nelle case dell'alta borghesia, dilettavano se stessi

e il prossimo facendo musica.