Compostela medieval

Porque trobar...

medieval.org

Fonti Musicali fmd 216

1998

1. Lai non par [12:10]

Paris, BN Fr844 “Manuscrit du Roi”

2. Guiraut de BORNÈLH. Reis Glorios [12:04]

Rome, Biblioteca Vaticana, Chigi CV150

3. Guillaume de POITOU. Companho ferai un vers disconvinen [7:02]

Paris, BN, lat 856

4. Eyns ne soy ... Ar ne knuthe [12:28]

London Guildhall

Cantigas de Santa Maria

5. Quen entender quiser, entendedor [3:30]

CSM 130

6. [8:28]

En tamana coita non pode seer ·

CSM 131

Quen leixar Santa Maria ·

CSM 132

Resurgir pode e faze-los seus ·

CSM 133

7. [4:07]

A Virgen en que é toda santidade ·

CSM 134

Aquel podedes jurar ·

CSM 135

8. Poi-las figuras fazen dos santos remenbrança [2:48]

CSM 136

harp prelude [1:42] based on

CSM 123

9. [3:47]

Sempr'acha Santa Maria razon verdadeira ·

CSM 137

Quen a Santa Maria de coraçon ·

CSM 138

10. Maravillosos e piadosos [3:56]

CSM 139

PORQUE TROBAR...

John Wright

Equidad Barès — voix, percussions

Françoise Johannel — harpe, organistrum

Anello Capuano — citoles, luth, percussions

Olivier Cherès — vièle ovale

Francisco Luengo — vièle droite

John Wright, voix — vièle ovale, organistrum

Compostela medieval

Porque Trobar e cousa en que jaz entendemento,

poren quen o faz áo d'aver e de razon assaz...

(Opening line of the Prologue to the Cantigas de Santa Maria).

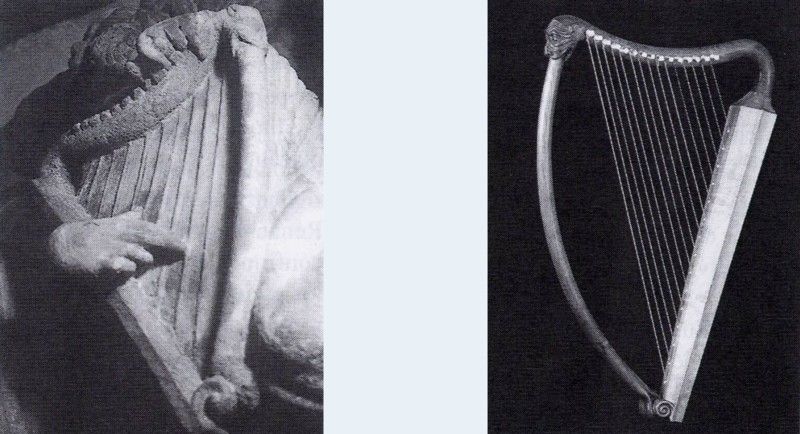

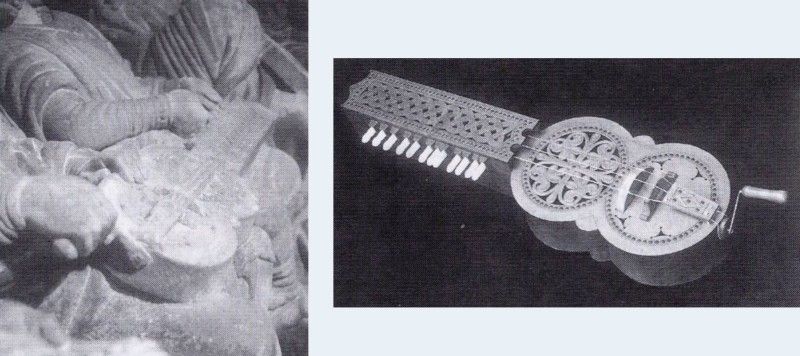

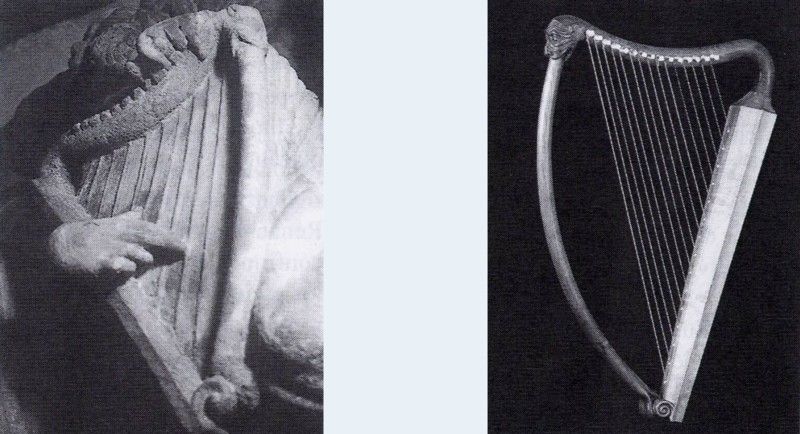

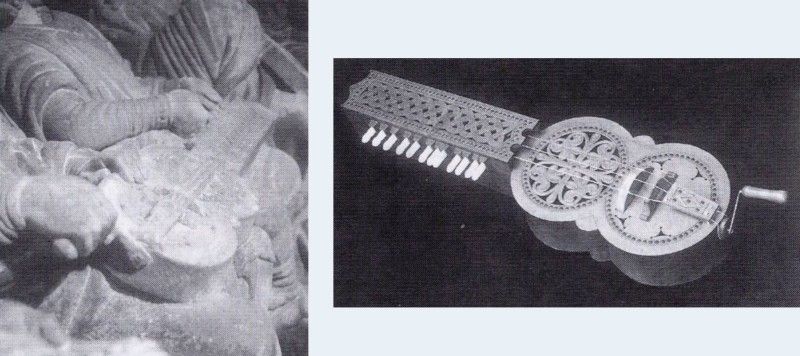

Trobar,

which broadly means “making a song”, also seems to imply the finding —

and seeking — of a pre-existent ideal form. Similarly, when realising a

working musical instrument based on mediaeval imagery, we are forced to

penetrate beyond the images in order to try to grasp the now-invisible

concrete reality that inspired them.

One name is associated with

the 12th Century Pórtico de la Gloria in Santiago Cathedral, that of

Mateo, Master of the works. We can nonetheless take it for granted that

the actual execution, or even the working out of details, was delegated

to several anonymous sculptors, at least one of whom obviously possessed

intimate knowledge of musical instrument construction. The five-string

oval fiddle in particular (one of the earliest traces of a type of

instrument extremely common throughout the Middle Ages) is represented

no less than eight times on the Pórtico with front, back and side views —

a veritable exhibition.

Even so, we are left with many open

questions. For instance, what was the exact scale of the sculptures and

thus the size of the originals? Is the number of strings correct on the

harps and psalterions? — and of course we have no idea of the materials

used nor plate-thicknesses.

We therefore have to place much reliance

on comparative studies of other documents of all kinds. But when all

comes to all, nothing can replace empirical trial and error; hand and

ear are the best judges, — but in this are we not simply treading in the

footsteps of mediaeval man?

Interpretation problems posed by the

12th and 13th Century songbooks from which Porque Trobar... draws its

repertoire call for a similar blend of factual knowledge and creativity.

Whilst the words may have been written compositions, detail variations

in the tunes lead us to believe that we are dealing with transcriptions

of what was basically oral tradition. In interpreting it we are once

again forced to “read between the lines” referring to our present-day

experience of orally-created music.

Rhythm is a particularly

thorny problem, as sometimes the measure is implicit in the notation,

sometimes not, with many shades between the two extremes. In all cases

it is advisable to base one's choices on the scansion of the text for,

as with present-day oral tradition, music is always servant to the

poetic text. In some ways mediaeval notation has the advantage over

modern transcription in that it gives flexibility in the representation

of a type of music that is always in a permanent state of flux and where

overall structure is the most important thing to grasp, the details of

the notation giving an idea of typical practice rather than direct

orders for interpretation.

We might draw a parallel with the

cahiers de chansons, carefully calligraphed exercise books still very

common in the French countryside. The songs in them are not necessarily

part of a singer's usual repertoire, but seem to be written down for the

beauty of the act. Could this also be true of the mediaeval

chansonniers?

And if it is art we are dealing with, the element

of craftsmanship is never entirely absent from this poetry. Did not

troubadours like Marcabru and Giraut de Bornèlh use the metaphor of

“sharpening- stone and steel” to hone the tools of their trade? One of

the songs in this disc, the Lai non par can be seen as a stylistic model, a template for fin trobar. And it so happens that, without any deliberate intention on our part, a fair number of pieces presented here are anonymous.

Porque

Trobar... dedicates this disc to all those unknown and unsung handlers

of chisel and pen who so brilliantly recorded the intelligence of their

times.

The Gelmirez Project took place in 1993 at the

Musical Instrument Workshop of the Deputation of Lugo in Galicia, Spain

(Obradoiro de Instrumentos Musicáis. Centro de Artesania e Deseño) -

director, Luciano Perez.

The aim was to re-create a number of

working mediaeval stringed instruments as prototypes for subsequent

reproduction at the workshop. Previous research (1988-1992) on the

Pórtico de la Gloria (1188) in Santiago de Compostela Cathedral had

clearly shown that 12th Century instruments were neither primitive or

rustic.

Our approach was to pick out details which seemed to us

to reflect constant parameters governing the working of stringed

instruments in general. In other words to “look for the familiar in the

unfamiliar”. We also studied the possible influence of geometrical

methods for tracing the outlines.

The main focus of our studies

was upon the instruments represented on the corbils (circa 1270) in the

great banqueting hall of the Palacio de Gelmirez at Santiago de

Compostela. We also reproduced a small selection of instruments in the

hands of the Elders of the Apocalypse on the Portico as this seemingly

inexhaustible mine of information provides the key to the understanding

of stringed instruments throughout the Middle Ages.

Francisco

Luengo, Christian Rault and John Wright were responsible for the

research, development and designs of the prototypes, the instruments

being built in the workshop by the permanent workmen, Antonio Franco,

Carlos Galván, Jesús Pérez and Germán Arias.

The result is a unique

collection of working replica instruments which, both visually and

musicnlly, in Galicia and beyond have stimulated the imagination of a

wide and varied audience.

We should add that all the participants

in the Gelmirez project were previously involved in Barrié de la Maza

Foundation project (1988-92) which concentrated entirely on the

reproduction of the instruments on the Pórtico de la Gloria in Santiago

de Compostela Cathedral, scaffolding being especially erected to allow

direct access to the sculptures. Without the essential information

gleaned during this unforgettable experience, the Gelmirez Project

simply would not have been possible.

The 12th and 13th Centuries

have been variously described as “the First Renaissance” or “the First

Industrial Revolution”: our work on the Pórtico and in the Palacio

Gelmirez has more than confirmed this and has convinced us that the

original instruments that inspired the sculptures were the result of

fundamental acoustical and technological research of remarkable quality

which provided the basis for modern lutherie.

The group Porque Trobar...

was formed in 1994 in order to exploit the prototype instruments built

during the Gelmirez Project. All the members, of varying musical

horizons, have in common experience in oral traditional music and this

colours their reading of the musical texts. The arrangement of the music

is a communal effort, the fruit of everyone's capacity for invention

and experiment. Although, as with the development of the instruments, we

were “looking for the familiar in the unfamiliar” there is no attempt

to adapt it to modern tastes.

The repertoire comes entirely from 12th

and 13th Century French and Spanish songbooks. It consists of pieces by

Guiraut de Bornèlh, Guillaume de Poitou and anonymous troubadours;

there are also extracts from the Cantigas de Santa Maria, the famous songbook commanded by Alphonse the Wise.

John Wright

The instruments used in this record were all built as part of the

above-mentioned project. Very little is known about the musical uses

for which these instruments were intended. Due to the hypothetical

nature of our instrumentation, the instruments had to be adapted to suit

our own choice of repertoire. For all the pieces here, the reference

note is D (A = 415Hz). Tunings and intonation are based upon the

Pythagorean scale in accordance with mediaeval theory.

5-string oval fiddles (Pórtico)

These

are offset-drone fiddles. We have adopted the first of the three

tunings given at the end of the 13th Century in the treatise by

Geronimus of Moravia, a Parisian scholar. Transcribed into our key, this

gives A4 - A4 - D4 - D3 - A3. This tuning not only lends itself to

drone playing but also possesses fascinating polyphonic possibilities.

4-string upright “long” fiddle (Gelmirez)

The

instrument in the original sculpture has 3 strings. The neck is broken

off and Francisco has interpreted the instrument as a long necked type

which figures in the Cantigas de Santa Maria miniatures. He has added an

offset drone and tunes the fiddle in several different ways, most often

A3 - D3 and A2 - G2.

Harp (Gelmirez)

This 15-string

harp is very light and fragile and gives a very sweet tone. It is tuned

to a diatonic scale extended to include major and minor sevenths in

accordance with mediaeval theory and practice.

Citoles, 3 & 4-string (Gelmirez)

This

strange instrument type with its “flying buttress” behind the neck, was

in vogue from the 13th Century onwards for a period of only about 200

years. Much research still remains to be done on it. Tuning: the small

4-string instrument C5 - G4 - D4 - A3 and the larger one, A3 - D3 - A2.

3-string lute (Pórtico)

Two

of these instruments are represented on the Pórtico de la Gloria. Their

interpretation poses a number of problems regarding certain details,

especially the belly which could either consist of a wooden plate or a

membrane. Ours has a membrane. Tuning - D4 - A3 - D3.

Organistrum (Pórtico)

This

giant ancestor of the hurdy-gurdy had to be played by two people, one

turning the rosined wheel by means of the handle and the other stopping

the notes with the keys. The organistrum was very likely used as an aid

for composing organa, providing the tenor. Tuning - A3 - E3 - A2.

John Wright

1 • Lai non par — Paris, BN Fr844 (“Manuscrit du Roi”)

Anonymous

piece, probably very early from the troubadour repertoire. Although the

main theme is a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, the principal motifs of

troubadour expression are present - the lady, the jealous husband, the

slanderers, the state of joy, etc. Lays are generally admitted to be a

Breton (or British) genre; certain rhythm patterns suggested by the

scansion of the text, plus passing allusions to Arthurian legend,

certainly lend weight to this notion.

Finely and joyously I begin for you a lay without compare...

A joyful tune for the Lady that the lover is about to leave behind. It

is the duty of every nobleman to undertake a journey to the Holy Land.

Although he must serve through suffering, the thought of the Noble Lady

gives him strength, courage and peace. And amid the bitter groans of

jealous husband, he sets out for the River Jordan. His prayers go forth

to the Saviour for the pardon of his sins and that he might return to

the castle of Blanchefleur, to his beloved.

2 • Reis Glorios... Guiraut de Bornèlh (...1162-...1199). Rome, Biblioteca Vaticana, Chigi CV150.

Alba

or “dawn call”. The dialogue takes place between a man keeping a

lookout for his friend who is spending the night with his lady. The

refrain And soon it will be dawn... is a warning not to tarry too long.

This setting has been conceived to set off each individual instrument as in turn they take the prelude to each verse.

The

watchman begs the Glorious King (of Heaven) to lend aid to his fine

companion. He tells the latter to sleep no longer, for the star

heralding the dawn is rising in the East, the bird is singing in the

bush and he fears that the “jealous one” will get him. He assures him

that he has not risen from his knees all night praying for his safe

return. The lover answers that he holds and embraces the fairest one

ever born of mother and he cares not for the jealous madman nor the

dawn.

3 • Companho farai un vers disconvinen... Guillaume de Poitou, 9th Duke of Aquitania (1071-1126). Paris, BN, lat 856.

The

music, which incorporates this text in Latin, is to be found in the

Saint-Martial manuscript (BN, lat. 1139) associated with the conductus, Promat chorus hodie, o contio. Certain similarities with the Reis Glorios tune suggest a common origin which is why we have juxtaposed the two pieces.

Companions,

I'm going to make a rude song, and in it there will be more folly than

sense. And you can call him a boor that does not understand it...

Comparing two horses, both of great worth and whose qualities he vaunts,

the problem being that he cannot keep them together as they cannot

stand each other, the singer asks for advice on the choice he must make

between...Lady Agnes and Lady Arsene!

The musicians here improvise “horse” interludes.

4 • Eyns ne soy... / Ar ne kuthe... Anonymous London Guildhall.

The

song of a prisoner, in Anglo-Norman French, followed by a translation

in Middle English on the same page of the manuscript, (12th Century?).

Both versions are sung successively here separated by a musical dialogue between harp and 4-stringed citole.

The

singer implores Jesus Christ, truth of God, truth of Man, to free him

from the prison in which he and his companions have been thrown without

reason, living in anguish and shame. Mad is he who trusts in this mortal

life and believes he can escape from trickery. Now we are in joy, now

in sadness; now fickle Fortune brings a remedy, now it wounds us. May

the Maiden that bore the Heavenly King beseech her son, that sweet thing

to free us from the evil one and bring us out of this place.

Cantigas de Santa Maria, 130 - 139.

From

the famous 13th Century songbook in Gallego-Portugese commissioned and

supervised by the King Alphonso X, “the Wise”. Over 400 songs with their

tunes are grouped together in this songbook (which exists in three

versions) recounting the miracles of the Virgin Mary. They are grouped

in sequences of ten, each set beginning with a hymn to the Virgin. We

present here a whole sequence of tunes in numerical order, some sung

with extracts from the texts, whilst others are instrumentals.

5 • Cantiga 130: Sung cantiga. This is in praise of Saint Mary accompanied by the organistrum.

Whoever wishes to know, should be knowledgeable of the Mother of our Lord.

6 •

Cantiga 131: Sung cantiga, prelude by the 4-string citole.

This

is about how Saint Mary saved the Emperor of Constantinople from being

crushed under a falling rock, and how all of the rest who were with him

died.

Cantiga 132: Sung cantiga.

This is about how Saint Mary made a priest, who had promised her chastity but married instead, leave his wife to serve only Her.

Cantiga 133: Instrumental dialogue.

This is about how Saint Mary brought back to life a young girl who had been lain dead before her altar.

7 •

Cantiga 134: Oval fiddle solo with tambourine accompaniment.

This

is about how Saint Mary in her church in Paris gave shelter to a man,

and many others who were with him, who had cut off his leg because of

the great pain he had of Saint Martial's fire.

Cantiga 135: Sung cantiga, prelude by the harp, based on the Cantiga 123 [sic; the prelude is in track 8, Cantiga 136]

How

Saint Mary kept from deshonour a young couple who had sworn by her when

they were children that they would marry one another, and how she made

them keep their promise.

8 • Cantiga 136: Harp/citole duet.

This

is about how in the Land of Pulla, in a village called Foia, a woman

was playing dice outside a church with her friends, and since she lost,

she threw a stone, which was going to hit the Child held by Saint Mary

who raised her arm and received the blow herself.

9 •

Cantiga 137: Sung cantiga.

How Saint Mary made a gentleman, who had been full of lust, chaste.

Cantiga 138: Instrumental tutti.

How

Saint Joan Boca-d' ouro, because he praised Saint Mary, had his eyes

gouged out and was exiled and stripped of his patriarchate; and then

Saint Mary returned his sight, and through her he earned his divinity.

10 • Cantiga 139: Sung cantiga.

How Saint Mary made the Son in her arms speak to the child of the good woman who had said “to eat”

Remerciements

Jeff Barbe

Bernard Ménétrier

Catherine Perrier

Keith Ammerman

Centro Galego de Bruselas

lieu d'accueil et de rencontres toujours ouvert aux projets culturels.

Unidad de Diseño C.A.D.G.

pour les idées de presentation et pour les documents de la couverture.

Photos

Obradoiro Instrumentos Musicáis

John Wright

fonti musicali, Bruxelles

Porque Trobar..., Paris

Obradoiro Instrumentos Musicáis, Lugo

Enregistrement:

Lou & Claude Flagel

NAGRA Digital

Micros: Bruel & Kjxr

Mastering: Sonic Solution

Local: The Right Place, Bruxelles.

1998

Patrocinado por:

Centro de Artesanía e Deseño de Galicia

Deputación Provincial de Lugo