The Mystery of Notre-Dame. Chant & Polyphony / Orlando Consort

Plainchant and organum from the Magnus liber organi

for the Feast of St. Stephen, Easter and the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

medieval.org

Archiv 453 487

1997

Easter

1. Pascha nostrum immolatus [1:45]

Communion

2. Et valde mane una sabbatorum à 2 [10:27]

Matins responsory

3. Victimae paschali laudes [2:25]

Sequence

4. Cristus resurgens — Dicant nunc à 3 [6:06]

Processional Antiphon

Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

5. Benedicta à 3 — Virgo, Dei genitrix à 3 [16:09]

Gradual

6. Alleluya à 2 — Assumpta est Maria à 2 [8:06]

Alleluya

7. Beata es, virgo Maria [2:16]

Offertory

Feast of St. Stephen

8. Etenim sederunt principes [4:15]

Introit

9. Sederunt principes à 4 — Adiuva me, Domine à 4 [16:22]

Gradual (PEROTINUS)

10. Alleluya à 2 — Video celos apertos à 2 [6:43]

Alleluya

11. Video celos apertos [1:32]

Communion

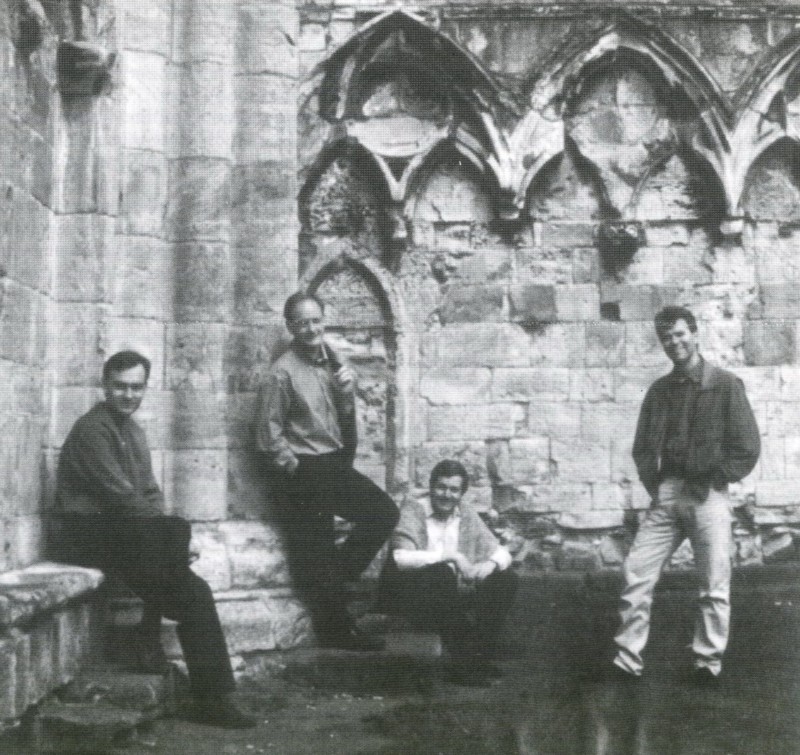

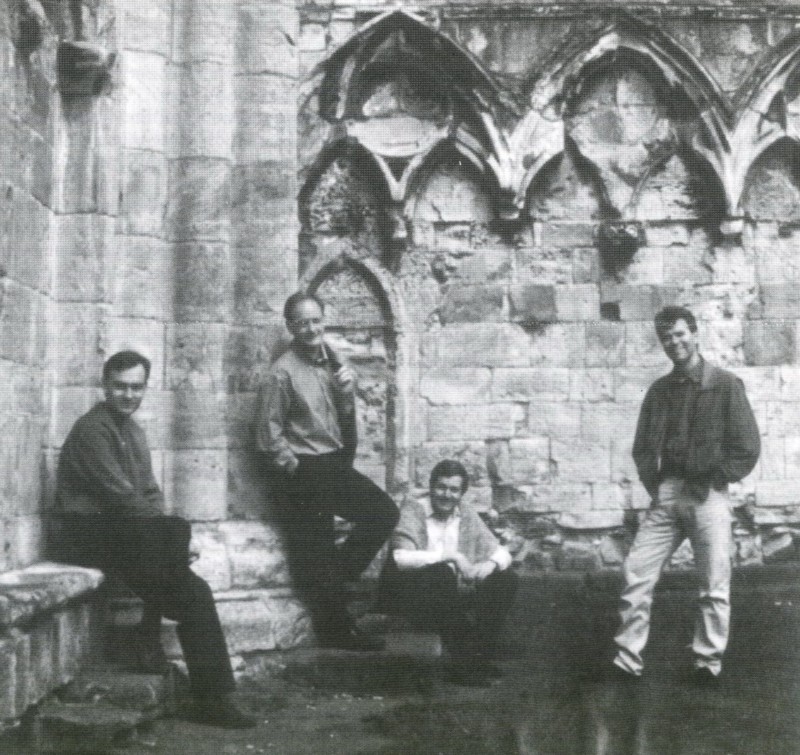

ORLANDO CONSORT

Robert Harre-Jones — alto | director of plainchant

Charles Daniels — tenor • Angus Smith — tenor

Donald Greig — baritone

with Simon Berridge — tenor

Plainchant:

Choristers of Westminster Cathedral Choir

Gerald Beatty • Matthew Davies • Benedict Durbin • Dominic Walker — trebles

Master of Music: James O'Donnell

Stephen Charlesworth • Charles Pott — baritones

Michael McCarthy • Julian Clarkson — basses

DDD 4D

Recording: Mandelsloh (Neustadt), St. Osdag Kirche, 5/1996

Executive Producer: Dr. Peter Czomyj

Recording Producer: Arend Prohmann

Tonmeister (Balance Engineer): Gregor Zielinsky

Recording Engineer: Reinhild Schmidt

Editing: Oliver Rogalla

Editions: Prof. Mark Everist. The music appears in vols. 1-4 of Le Magnus liber organi de Notre Dame de Paris, 7 vols. (Monaco: Editions de l'Oiseau Lyre, 1994)

P 1997 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg

C 1997 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg

Complete art work by Seib Werbeagentur, Hamburg

Illustration "Ile de la Cite" • Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris

Artist Photos: Suzie Maeder (Orlando Consort) · Joachim Rilhl (Mandelsloh)

Art Direction: Lutz Bode

Printed in Germany by/ Imprimé en RFA par Münstermann, Hannover

NOTRE DAME POLYPHONY

The history of late 12th-century polyphony was first written a hundred years after the

event

by a monk who may have come from the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds; the

past has not entrusted us with his name and he is usually referred to by

the title he received when his treatise was first published in the 19th

century: Anonymous IV. Anonymous as he was, he tells us about two of

the most important composers of the fifty years either side of 1200: the

magistri Leoninus and Perotinus. Leoninus, we are told, wrote a

cycle of two-part settings of the most important chants in the

liturgical year - Christmas, Easter, Assumption and other feasts; this

cycle was called the Magnus liber organi - the great book of

organum. Perotinus and his contemporaries played an important role in

the careful recasting and elaboration of this repertory. According to

the monk from Bury St. Edmunds, Perotinus either shortened or edited

(interpretations vary) Leoninus' great book of organum; long sections of

almost improvisatory scope were rewritten according to the tighter

principles of discant composition that Perotinus himself may have

contributed to codifying. Perotinus wrote organa in three and four parts, and Anonymous IV mentions two works by name: Sederunt principes

is one of these. Both Leoninus and Perotinus worked at the Cathedral

Church of Notre Dame de Paris; while little is conclusively known about

the biography of Perotinus, recent fashion has inclined to identify

Leoninus with Leo, a canon of Notre Dame in

later life and, incidentally, an author of neo-Ovidian homoerotic poetry.

Musical

contributions to the liturgy at the Cathedral Church of Notre Dame were

of two types: monophony (liturgical chant) and polyphony (organum).

Routine celebration of the Mass and Office was accompanied by a number

of plainsong items; in addition to the Ordinary of the Mass, each feast

was marked out by its Proper liturgical chants: introit, gradual,

alleluya, sequence, offertory and communion (for the Mass) and

responsories (for the Office) During the last third of the twelfth

century, Leoninus and Perotinus selected some of these chants for

reworking in polyphony; Leoninus and his generation composed in two

parts (organum duplum) while Perotinus and his colleagues also composed for three and four voices (organum triplum and quadruplum).

Organa of the type that make up Leoninus' Magnus liber organi,

and of the type at which Perotinus and his contemporaries excelled, are

polyphonic settings of plainsong. The original chants employ two

musical styles: the solo sections are elaborately melismatic and

contrast with the simpler, more syllabic, sections sung by the schola. It is the melismatic solo sections of the chant that are set polyphonically. The result is that a performance of organum involves polyphony and plainsong. Sederunt principes and Benedicta

are both graduals and have the overall structure Respond - Verse -

Respond. Within each of these main sections are settings of both solo

and choral chants; the Respond consists of polyphony followed by the

remainder of the chant, and the same pattern is followed in the verse,

and of course in the return of the respond. Usually, the second respond

is simply a repeat of the first one, as in the case of Benedicta; in Sederunt principes, the repeat of the respond is fully written out.

Leoninus' organa dupla of the Magnus liber organi

took the plainsong and did one of two things with it: he laid out the

lowest part (the tenor) in long notes and wrote highly elaborate,

rhapsodic lines above it (the duplum); this style of music was called organum per se (medieval terms vary, and theorists took a pedantic pleasure in pointing out the complexities of usage for a term - organum

- that could mean a complete piece or a generic style or - as here - a

subsection). Alternatively, he took the long melismas of the chant and

organized them into repeating rhythmic cells and wrote a correspondingly

tight rhythmic duplum above it. The rhythmic organization of this procedure gave rise to what are called the rhythmic modes (this style was called discantus).

Both types of music exist within the same composition; the sections

based on highly melismatic chants that use the rhythmic modes are called

clausulae when they are given discrete, self-contained forms.

In some respects, the organa tripla and quadrupla

of the next generation are similar: they take the solo sections of the

chant only, and subject them to a polyphonic treatment. When writing for

three and four voices, however, the composers adopted different

attitudes to rhythm. In the clausulae - as in organum duplum - rhythm and metre are carefully controlled, and the resulting structures are complex and sophisticated. In contrast to organum duplum, the organa tripla and quadrupla

do not adopt such an abruptly different style for the rest of the

polyphony; here, the composers again employ the sustained-tone tenor

(the liturgical-chant in long notes) but now set the two or three upper

voices in the same sorts of rhythmic patterns found in clausulae

- in other words, patterns where rhythm and metre were strictly

controlled. The result is a composition in which the performative

flexibility of organum duplum is banished but one in which the composer can fix musical ideas with precision and durability.

The

Orlando Consort have selected music from three of the major feasts from

the liturgical year: Easter, the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

and the Feast of St. Stephen (26 December). They have merged this focus

on three feasts with a range of liturgical items: introit, gradual,

alleluya, offertory, communion, responsory and processional antiphon,

and offer a range of musical styles: plainsong, organum duplum, triplum and quadruplum.

It used to be thought that the sustained notes in organum duplum

were to be held relentlessly: a challenge to breath control and the

sanity of the singer taking the part. Re-readings of 13th-century theory

suggest that the tenor is responsible for contributing with great

subtlety to the texture of the work by breaking the sound, at the same

time as one or more of the upper voices, and this is the procedure that

the Orlando Consort employ in the recording here.

Although the presentation of the upper voices in the three- and four-part works is largely uncontentious, performing the duplum lines in organum per se

is a skill that is difficult to regain at the end of the 20th century.

The music notated in the original manuscripts give a mixture of

information: some idea of what the composer's overall structure might

have been, an idea of at least one (and probably more than one)

performer's view of the music - and it has to be remembered that a

performer's "view" of this music would almost certainly have entailed

changes to pitch and rhythm, and a sense of what a 13th-century editor

would have done in trying to copy down and render consistent a wide

range of material. So these sections which, in their floridity, resemble

late 18th- and early 19th-century coloratura vocal lines, differ in

that they are not just blueprints to be ornamented; they are blueprints

that have already been partially ornamented, and the singer of the duplum

part treads a very careful path between the slavish duplication of a

medieval performer's view of the work and the complete recreation of

Leoninus' music.

The plainsong on this recording is performed by boys and men that formed the basis of the schola,

and is present in every number either in order to complete the

liturgical structure of the individual items or as the single mode of

presentation in liturgical chant; in the case of the monophony, the use

of men and boys serves to contrast the solo and schola sections of the music very clearly.

The

editions of the music used in this recording are taken from the

manuscripts Florence, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Pluteus 29.1

(polyphony) and Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, fonds latin

1112 (plainsong).

Mark Everist

ORLANDO CONSORT

Formed

in 1988, the ORLANDO CONSORT has rapidly achieved a reputation as one

of the most accomplished and challenging groups performing repertoire

from the 11th to the 15th centuries. All the singers in the group are

established soloists and have appeared frequently with groups such as

the Tallis Scholars, and the Gabrieli and Taverner Consorts.

Collaborating

with leading academics on music that has rarely if ever

been performed in modem times, they have set new standards of

performance, particularly with regard to the tuning and pronunciation of

their chosen repertoire.

The Orlando Consort gave

highly-acclaimed concerts at the Utrecht Early Music Festival in 1989,

1990 and 1996. In 1991 and 1995 the group undertook extensive tours for

both the British and Dutch Early Music Networks. The Consort has

appeared in festivals in Belfast, York, Brinkburn, Santander, Antwerp,

Bruges, Berlin, Cologne, Frankfurt, Prague, Graz and Padua, as well as

in the USA and Canada. They were artists-in-residence at Queen's

University, Belfast, for the academic year 1993-94, and in 1996 received

the Noah Greenberg Award of the American Musicological Society. Their

recording of sacred choral works by Dunstable won the Gramophone's Early

Music award in 1996.

The present recording is the second the

group has made since signing an exclusive contract with Deutsche

Grammophon /Archiv Produktion in 1996; the first was of Ockeghem's Missa

"De plus en plus" and a selection of his chansons (DG 453 419-2).

Future projects include a recording of chansons by Machaut.

The School of Notre Dame / Orlando Consort

LÉONIN • PEROTIN

medieval.org

Archiv 477 5004

2004

CATHEDRAL VOICES

THE ORLANDO CONSORT SINGS MUSIC FROM THE "MAGNUS LIBER ORGANI"

In

1163 Pope Alexander III laid the foundation stone for a building that

was to be one of the most daring of all medieval edifices: the Cathedral

of Notre Dame in Paris remains a miracle of ecclesiastical

architecture, its interior and exterior impressing the observer equally

with their powerful and yet seemingly weightless appearance. The work of

several architects, the cathedral took almost a century to build, a

timescale that is in delightful contrast with the unity of its overall

impression.

Even before the building work was complete, a

further, audible change had taken place within the cathedral, a change

that marked a sudden and decisive development in polyphonic music and

that was brought about in particular by the two leading musicians at

Notre Dame, Leoninus and Perotinus. Thanks to these two composers, the

newly built cathedral became the focus of a musical revolution far

greater than anything previously known. If we are able to trace this

development today, more than eight hundred years later, we owe this in

part to the labours of musicologists, but also and above all to

ensembles that have specialized in performing this music and in that way

brought these scholarly discoveries to life. There is no doubt that the

Orlando Consort is one of the most progressive groups of its kind.

Through their association with musicologists and their regular

appearances at early music concerts, this four-man ensemble has set

standards of performance practice that others have striven to emulate.

In particular, their interpretations are characterized by sensitivity to

matters of intonation and pronunciation. After such a lengthy period of

time, today's audiences can gain access to this fascinating music only

if its interpreters allow us to experience its spiritual content, too.

And it is very much this that sets the Orlando Consort apart from other

early music ensembles. As the Gramophone critic wrote in 1997

on the occasion of the group's first release on the Deutsche Grammophon

label, "they sing with such refined intonation that the music is

irresistible". That this music would ever be described as "irresistible"

is something that earlier generations of musicologists would never have

thought possible.

The Orlando Consort owes its success not just

to its refined intonation but also to its diction: its French

pronunciation of the Latin words colours the liturgical text and invests

it with that lean-toned character that recalls Gothic pillars soaring

skywards. Synaesthetic impressions of this kind were by no means unknown

in the early Middle Ages, for richly ornamented melismas in the solo

sections were clearly intended to carry an additional layer of meaning.

The Orlando Consort has found a way of performing early polyphony so

that it constitutes a positively sensual veneration of God.

The

interpretation of the organa dupla — two-part settings — demands a skill

on the part of the performers that consists not just of vocal technique

but also of an ability to imbue the text with meaning, for the original

notation offers only hints at what the composer may have intended in

terms of musical texture. As a result, today's singers have the task of

putting themselves in the position of singers from the Middle Ages and

at the same time fathoming the practices associated with 12th-century

notation. All of this demands a considerable intellectual effort to come

to terms with the spirituality of the period. The upper part of the

duplum will succeed only if the singer knows what he is doing from a

stylistic point of view: modal rhythm must be understood, and the often

rhapsodical melodic lines must be meaningfully structured and related to

the tenor line beneath them. To achieve this requires the singer to

perform a tightrope walk between merely imitating his medieval

counterpart and attempting to breathe life into the notated musical

texture. The Orlando Consort has won awards not least for its ability to

invest the music it performs with a very real sense of spirituality.

The

complex nature of the music written for Notre Dame emerges above all

from the three- and four-part pieces in which the singers Robert

Harre-Jones, Charles Daniels, Angus Smith and Donald Greig use their

voices to create an apparently endless sense of space. Clearly intoned

intervals and melismas convey a feeling of the solemnity that reflects

the liturgical occasion. The singers have chosen liturgies from three of

the Church's main festivals: Easter, the Assumption of the Blessed

Virgin Mary and the Feast of the protomartyr St Stephen on 26 December.

The undoubted high point of the ensemble's interpretation is their performance of Perotinus's Sederunt principes,

which was written for the liturgy of the Feast of St Stephen. This

four-part gradual follows a monophonic introit and reveals the whole

richness of the musical texture: the solo section of the previous

chorale is polyphonically reworked, the tenor now being entrusted with

the extended chorale melody, while the three upper voices accompany it

with their melismatic lines. The modal rhythm of these upper voices is

fixed, in which respect it differs from that of the two-part organum.

The performers are thus denied some of the spontaneity that the duplum

offers its singers, but instead we have a chance to hear the composer's

precise instructions realized. More than eight hundred years after these

fascinating polyphonic pieces were written, the lean-toned cathedral

voices of the four members of the Orlando Consort create the impression

of messengers opening up a remote and unknown world to us for the very

first time.

Ulrike Brenning

(Translation: Stewart Spencer)

IM KLANG DER KATHEDRALE

DAS ORLANDO CONSORT SINGT AUS DEM »MAGNUS LIBER ORGANI«

Im Jahre 1163 legte Papst Alexander III. den Grundstein für einen

Kathedralenbau, der zu den mutigsten Entwürfen der

mittelalterlichen Architektur werden sollte: Die Kathedrale Notre-Dame

zu Paris ist noch heute ein Wunderwerk des Kirchenbaus. Außen wie

innen beeindruckt sie durch ihre gewaltige und dennoch schwerelos

wirkende Erscheinung. Trotz ihrer fast 100 Jahre währenden Bauzeit

unter der Leitung verschiedener Baumeister bietet sie ein reizvoll

geschlossenes Gesamtbild.

Während dieser Zeit, als die Arbeiten noch nicht vollendet waren,

vollzog sich im Innern der Kirche bereits eine weitere, eine akustische

Revolution. Sie markiert eine sprunghafte Entwicklung der polyphonen

Musik, namentlich vorangetrieben durch Leonin und Perotin, die

führenden musikalischen Köpfe an Notre-Dame. Die eben neu

gegründete Kathedrale wurde durch sie zum Mittelpunkt eines

musikalischen Wirkens von weit größerer Intensität als

je zuvor. Dass wir das umwälzende Geschehen heute, mehr als 800

Jahre später, nachvollziehen können, verdanken wir einerseits

der Musikwissenschaft, andererseits aber vor allem Ensembles, die sich

auf diese Musik und ihre Ausführung spezialisiert haben und so die

wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse erst in eine sinnlich erfahrbare Form

bringen.

Zu den avanciertesten Ensembles dieser Art zählt zweifelsohne das

Orlando Consort, ein erstklassiges Männer-Vokalquartett. Durch die

enge Zusammenarbeit mit Musikwissenschaftlern und die rege Teilnahme an

Akademien für Frühe Musik setzt das Orlando Consort

Maßstäbe für die Aufführungspraxis, vor allem in

der Klanggestaltung und der Sprachbehandlung dieser faszinierenden

Musik. Sie kann sich einem Publikum nach so langer Zeit nur

erschließen, wenn es den ausführenden Sängern gelingt,

auch den geistigen Kontext dieser Musik wieder erlebbar werden zu

lassen. Und eben dies zeichnet das Orlando Consort auf ganz besondere

Art und Weise aus — »they sing with such refined intonation

that the music is irresistible«, urteilte der Rezensent der

Zeitschrift Gramophone 1997 anlässlich der Ersteinspielung bei der

Deutschen Grammophon. Dass diese Musik eines Tages als

»unwiderstehlich« bezeichnet werden würde, daran

hatten nicht einmal Generationen von Musikwissenschaftlern geglaubt.

Zur verfeinerten Intonation darf man auch die Diktion des Textes

zählen: Die französische Aussprache des Lateinischen

färbt den liturgischen Text und verleiht ihm jenen schlanken

Charakter, der an hoch aufstrebende gotische Säulen denken

lässt. Synästhetische Verschmelzungen dieser Art waren dem

frühen Mittelalter nicht fremd; bei reich ausgeschmückten

Melismen der Solo-Abschnitte war eine weitere Bedeutungsebene durchaus

intendiert. Das Orlando Consort versteht es, die frühe

Mehrstimmigkeit als sinnliche Verehrung Gottes vorzutragen.

Die Gestaltung der zweistimmigen Gesänge, der organa dupla,

verlangt von den ausführenden Sängern eine Geschicklichkeit,

die sich aus stimmlichem Können und inhaltlicher Durchdringung

zusammensetzt, denn die originale Notation bietet nur Anhaltspunkte

dessen, was sich der Komponist als Struktur gedacht haben könnte.

So fällt dem Sänger heute die Aufgabe zu, sich in den

Sänger des Mittelalters zu versetzen und darüber hinaus den

Gepflogenheiten der Notation im 12. Jahrhundert nachzuspüren; das

erfordert eine starke innere Auseinandersetzung auch mit der

Geistigkeit jener Epoche. Die Oberstimme des Duplum gelingt nur, wenn

der Sänger eine große Stilsicherheit in der Gestaltung

besitzt: Es müssen rhythmische Modi erfasst, die oft rhapsodischen

Melodielinien sinnvoll gegliedert und mit dem darunter liegenden so

genannten »tenor« klanglich verbunden werden. Es ist dies

eine Gratwanderung zwischen der Imitation eines mittelalterlichen

Sängers und dem Versuch einer Wiedererweckung der aufgeschriebenen

musikalischen Struktur. Nicht zuletzt für die geistige

Durchdringung der von ihnen aufgeführten Musik hat das Orlando

Consort renommierte Preise erhalten.

Die Komplexität der Musik an Notre-Dame kommt vor allem in den drei- und vierstimmigen Sätzen

zur Geltung, in denen die Sänger Robert Harre-Jones, Charles Daniels, Angus Smith und Donald

Greig mit ihren Stimmen eine unendlich wirkende Weite des Raumes

erzeugen. Klar intonierte Intervalle und Melismen vermitteln jene

Feierlichkeit, die dem liturgischen Anlass entspricht. Liturgien

für drei Hochfeste des Kirchenjahres haben die Sänger

ausgewählt — Ostern, Mariae Himmelfahrt und das Fest des

Erzmärtyrers Stephanus (26. Dezember).

Den Höhepunkt stellt die Interpretation des Sederunt principes von

Perotin dar, geschrieben für die Liturgie des Festtages des

heiligen Stephanus. Nach dem einstimmigen Introitus folgt dieses

vierstimmige Graduale und offenbart den ganzen Reichtum der

musikalischen Struktur: Der Solo-Abschnitt des vorausgegangen Chorals

erscheint in einer mehrstimmigen Bearbeitung, in welcher der

grundlegende Part (tenor) die weit ausgedehnte Choralmelodie

vorträgt, welche die drei Oberstimmen in melismatischen Linien

umranken. Die rhythmischen Modi dieser Oberstimmen sind — anders

als im zweistimmigen Organum — genau festgelegt. Die

Spontaneität der Ausführung, wie sie das Duplum den

Sängern bietet, ist hier zwar nicht gegeben, aber wir haben die

Möglichkeit, die präzisen Angaben des Komponisten hörend

nachzuvollziehen. Über 800 Jahre nach der Entstehung dieser

faszinierenden Mehrstimmigkeit wirken die schlanken

»Kathedral-Stimmen« der vier Sänger des Orlando

Consorts in diesem Zusammenhang wie Boten, die erstmals eine ferne,

unbekannte Sphäre erschließen.

Ulrike Brenning

DDD

Recording: Mandelsloh (Neustadt), St. Osdag Kirche, 5/1996

Executive Producer: Dr. Peter Czornyi

Recording Producer: Arend Prohmann

Recording Engineer: Reinhild Schmidt

Editing: Oliver Rogalla

Editions: Prof. Mark Everist: The music appears in vols. 1-4 of Le

Magnus fiber organi de Notre Dame de Paris, 7 vols. (Monaco:

Editions de l'Oiseau Lyre 1994)

Booklet Editor: Eva Zöllner

P 1997 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg

© 2004 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg

Orlando Consort: © Marco Borggreve / DG

Cover Photo: © zefa visual media / J.A. Kraulis

Art Direction: Nikolaus Boddin

Printed in the E. U.