Gloria 'n Cielo e Pace 'n Terra / Orientis Partibus

Songs of the age of St. Francis of Assisi

medieval.org

Dynamic 269

1999

1. Alle psallite cum luya [1:28] Codex Montpellier H 196

motet — lute, fiddle, bagpipe GB VV, tambourine BS

2. Festa dies agitur [3:07]

carol — voice MBo AP, fiddle, hurdy-gurdy, bagpipe VV, pipe and tabor, tambourine BS, sistrum

3. Angelorum glorie [5:58]

carol — voice MBo AP, fiddle, gemshorn GB VV, hurdy-gurdy

4. Verbum caro factum est [2:40]

motet — voice MBo AP, bagpipe VV, pipe and tabor, fiddle, lute, bendir BS

5. Concordi laetitia [2:23]

Marian hymn — voice MBo, lute, harp, psaltery, fiddle

6. Verbum patris humanatur [2:37]

conductus — voice MBo, lute, fiddle, medieval cylindrical recorder in G

7. Non sofre Santa Maria [1:28] Cantigas de Santa Maria

CSM 159

harp, fiddle, hurdy-gurdy, transverse flute, castanets, bendir VV

8. Pois que dos Reys [9:14] Cantigas de Santa Maria

CSM 424

voice MBo, sas, psaltery, fiddle, transverse flute, sistrum

9. Cleri cetus [5:49] Codex Las Huelgas

Hu 14

trope of Sanctus, organum — voice LS, fiddle, hurdy-gurdy, bagpipe VV, pipe and tabor

10. Gaude Virgo [3:03]

carol — fiddle, bagpipe VV, medieval cylindrical recorder in F

11. Verbum bonum et suave [2:05] Codex Las Huelgas

Hu 54

prose — voice LS, voice MBo AP, fiddle, hurdy-gurdy

12. Dies festa colitur [3:11]

carol — voice MBo AP, fiddle, hurdy-gurdy, double flute, tambourine BS, bendir VV

13. Stella nuova 'n fra la gente [8:19] Laudario di Cortona

voice AP, voice MBe MBo VV, hurdy-gurdy

14. Gloria 'n cielo e pace 'n terra [3:07] Laudario di Cortona

voice LS, lute, harp, fiddle, medieval cylindrical recorder in G, tambourine VV

Ensemble Orientis Partibus

on original instruments

Marco Becchetti — fiddle, voice

Roberto Bisogno — lute, hurdy-gurdy, sas

Mauro Borgioni — voice, sistrum

Giovanni Brugnami — transverse flute, pipe and tabor, bagpipe, double flute, medieval cylindrical recorder in G and F, gemshorn

Alessandro Pascoli — voice, tambourine, castanets

Luisa Sambuco — voice

Brunella Spaterna — harp, tambourine, voice

Vladimiro Vagnetti — bagpipe, gemshorn, psaltery, tambourine, bendir, voice

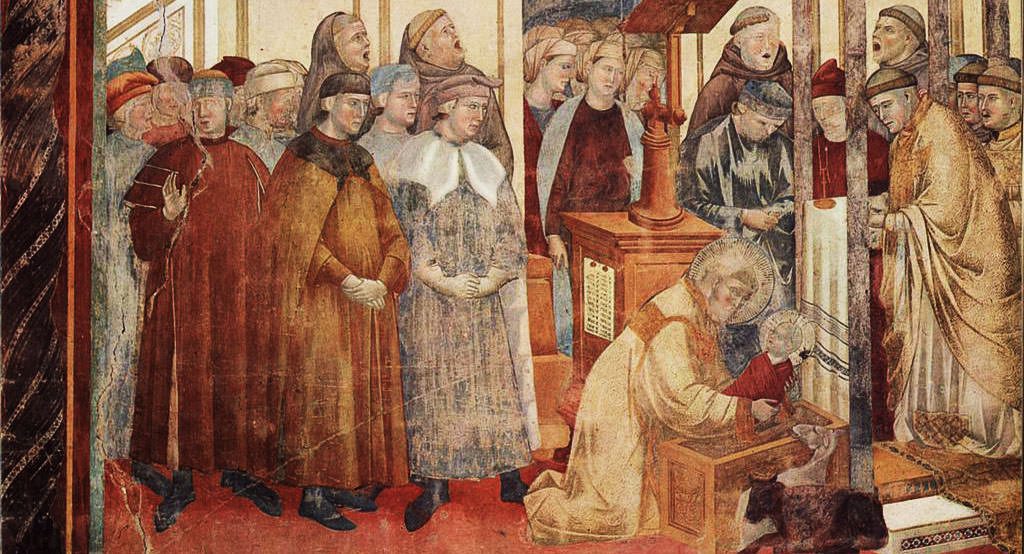

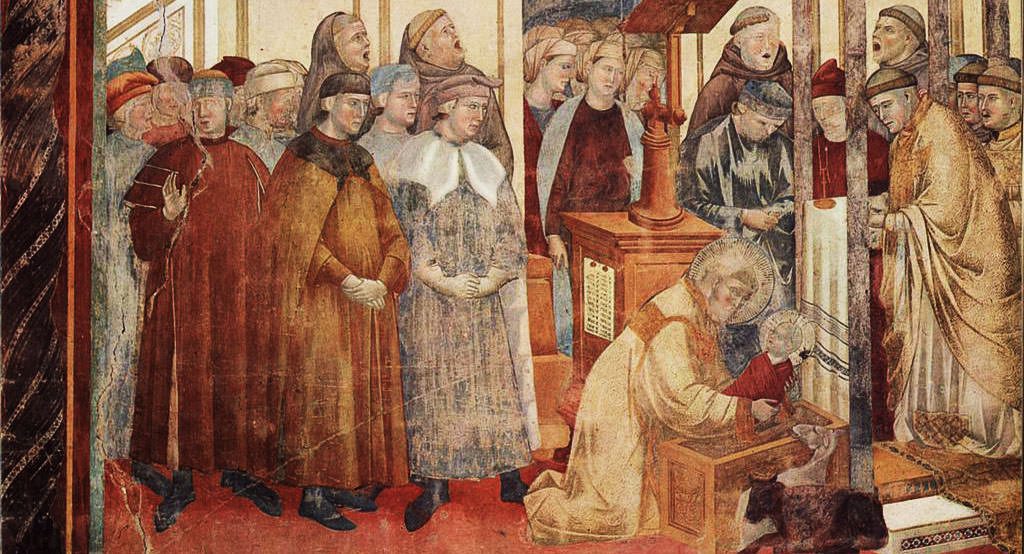

Cover: Proteo - Giotto: Presepe di Greccio

Computer graphics: Stefano Olcese

Recording & editing: Rino Trasi

Recorded at Chiesa di S. Giacomo di Muro Rupto, Assisi, July 1999 © 1999

Produced bu DYNAMIC S.r.l

http:/www.dynamic.it

English liner notes

GLORIA ‘N CIELO E PACE ‘N TERRA

La Pasqua è senz’altro il

momento culmine della liturgia cattolica, ma nella devozione popolare il

ciclo liturgico si sviluppa di fatto intorno a un’ellisse che ha come

punti focali la celebrazione della morte e risurrezione di Cristo,

mistero e dogma fondamentale della “Storia della salvezza”, ma anche la

celebrazione dell’incarnazione, della nascita di Cristo; entrambe

partecipate con grande solennità. Le innovazioni liturgiche introdotte

sulla scia dei generi musicali sviluppatisi nei centri più vivaci della

cultura di ogni tempo, riguardano dunque, a maggior ragione, le

solennità principali. L’ensemble Orientis Partibus propone in questo

disco un’antologia di brani musicali ispirati e composti per la festa

del Natale: quelli che entrarono a far parte della liturgia e quelli che

invece ne restarono sempre a margine, a commento devoto delle occasioni

paraliturgiche, provocati dalla pietà popolare, scritti nella lingua

del “popolo” e cantati in uno “stile” musicale più vicino a quello dei

laici, ad ogni modo sempre come complemento delle celebrazioni della

Chiesa; in alcuni casi tollerati dal clero, in altri accettati o

addirittura sollecitati dall’ambiente clericale. I brani appartengono ad

un ambito spazio temporale piuttosto vasto: Francia, Inghilterra,

Spagna, Italia tra i secoli XIII e XIV. Vengono proposti tropi e

conducti polifonici più inerenti alla celebrazione liturgica e canti di

devozione – carols, cantigas e laudi. Questi ultimi, se non per

l’ambiente socio-culturale in cui nascono e per la forma stilistica,

sono simili per le pie intenzioni di celebrare le vicende salienti della

vita di Cristo, della Vergine e dei Santi, e di muovere alla devozione,

attraverso il racconto degli eventi mirabili, non solo chi canta, ma

anche chi ascolta.

Sequenze e tropi, rappresentano le novità

inserite nell’ambito di una struttura liturgica ormai sta-bile.

Tralasciamo le questioni relative alle loro origini, che impegnano

tuttora la ricerca musicologica, e non tentiamo definizioni che, per

esigenza di brevità, risulterebbero comunque criptiche e incomplete, ci

limiteremo a dire che, passato il momento dall’affermazione e

divulgazione nella loro forma monodica avvenuta tra il IX e il X secolo,

questi canti nati in ambito liturgico costituirono la materia

ispiratrice sulla quale si incentrarono le prime forme di polifonia. La

sequenza, versi “inventati” applicati al vocalizzo dell’Alleluja,

può dirsi essa stessa un tropo, solo che nella sequenza non è ammessa

“nuova” melodia e la prosa deve essere cantata esclusivamente sui

melismi dell’Alleluja. I tropi invece, più liberamente, possono

introdurre nuovi versi su una composizione liturgica preesistente, o una

nuova melodia sui versi di un canto liturgico anti-co, o possono

costituirne il preludio o il complemento, come è per i tropi “insinuati”

nei temi dell’ufficio del breviario. Il conductus si afferma

intorno al IX° secolo nella Francia meridionale: in breve, si tratta di

una composizione vocale su testo latino la cui musica, come riferisce la

letteratura più accreditata sull’argomento, risulta essere composta ex novo;

il nome deriverebbe dalla funzione liturgica del canto, che doveva

accompagnare gli spostamenti del celebrante, ma anche, in senso

figurato, che aveva il ruolo di “condurre” cioè “guidare” verso momenti

diversi della liturgia. Col nascere della polifonia queste “forme”

musicali vengono scritte a più voci, in esse si applica la perizia e

l’ispirazione dei nuovi cantores, fino a giungere alle alte espressioni della Scuola di Parigi, detta di Notre-Dame, che tanto influenzerà la produzione musicale del XIII secolo e degli inizi del XIV.

Le

fonti da cui sono tratti i brani musicali proposti dall’Ensemble

Orientis Partibus in questo CD, provenienti da aree geografiche diverse,

dimostrano la diffusione e la permanenza di questi temi culturali e

musicali. È il caso del manoscritto de Las Huelgas, composto nei primi

decenni del XIV secolo, che testimonia - come del resto il manoscritto

della Biblioteca Nazionale di Madrid (Nr.20486) - che in Spagna grande

considerazione ebbero gli insegnamenti della così detta Schola di Notre-Dame.

Anzi il codice contiene molti brani provenienti da Parigi. Contiene

anche esempi di polifonia meno “ricchi”, appartenenti ad un periodo già

lontano dalla scrittura del codice, come il Verbum bonum et suave,

risalente all’inizio del secolo XII, a testimoniare il permanere

per lungo tempo nell’uso liturgico di alcune composizioni.

L’Ars Antiqua dimostra la sua completa evoluzione

nell’affermazione del mottetto, che costituirà anche un

“genere” di transizione verso l’Ars Nova, assumendo però nuove e diverse connotazioni.

Il mottetto si fonda strutturalmente su una voce di tenor

il cui testo è tratto dal repertorio liturgico, anche se da questo

diviene totalmente indipendente, e preferibilmente su altre due voci, motetus e triplum, che nel modello più antico cantano lo stesso testo del tenor; in seguito queste due voci saranno composte su testi differenti, affini a quello del tenor.

Questa forma approderà alla trattazione di argomenti anche profani,

satirici, amorosi o politici. Il manoscritto di Montpellier (Faculté de

Medecine H 196) costituisce una delle fonti più importanti per questa

forma musicale. Alcuni autori hanno voluto vedere nel mottetto Alle psallite cum luya

(qui proposto in versione strumentale), che apre il CD, tratto proprio

dall’ottavo fascicolo del citato manoscritto, la prova dell’influsso del

tropo sulle prime forme di mottetto, individuando, nelle due voci più

acute, un tropo, Psallite cum, che si inserisce tra Alle e luya del tenor.

Le Cantigas de Santa Maria la cui raccolta, avvenuta tra il 1252 e il 1284, si fa risalire all’opera di re Alfonso X el Sabio,

ci sono tramandate da quattro codici, tre dei quali con notazione

musicale, che rappresentano una delle testimonianze più importanti della

musica, della poesia ma anche dell’arte miniaturistica del Medioevo. I

codici conservano oltre 400 composizioni spirituali che raccontano i

miracoli della Vergine e si inspirano, in gran parte, ai Miracles de Notre-Dame del troviere monaco Gautier de Coinci. Dal punto di vista strutturale ricalcano il virelai

francese, essendo composte nella forma ritornello, strofa, ritornello,

anche se le varianti, dato questo schema fondamentale, sono numerose.

Aperta è ancora la questione sullo stile musicale e sull’interpretazione

ritmica; alcuni autori vogliono vedervi l’influsso della cultura araba

sia per ciò che concerne la forma letteraria che per quella musicale,

altri invece rifiutano completamente questa ipotesi. La confluenza e la

sovrapposizione di elementi provenienti dalle diverse culture, senza

estremizzare le posizioni dall’una o dall’altra parte, sembra comunque

storicamente pertinente e verosimile.

In Italia il canto

devozionale delle confraternite laicali, la lauda, nasce come punto

d’incontro tra ambito religioso e ambito profano. Scaturito

dall’entusiasmo religioso e dal ritorno alla “pietà” del popolo, si

alimenta al sentimento di “perfetta letizia” proprio della religiosità

francescana. Si allontana dal canto ecclesiastico usando un’altra

lingua, il volgare, e si ispira stilisticamente alla musica profana. Ma

il momento culmine del fiorire della lauda, fu la nascita di

confraternite che fecero di questa “pratica” il loro principale impegno

devozionale; la prima delle confraternite dette “Laudesi” di cui si

conosca l’attività, nacque a Siena nel 1267. Il sorgere e lo svilupparsi

del movimento dei “Disciplinati” fondato da Rainerio Fasani da Perugia

nel 1260, dette gran-de impulso alla pratica laudistica. Nella lauda

monodica il rapporto tra testo e melodia è strettissimo; la struttura

letteraria, strofa e ritornello, è molto simile a quella della ballata

di origine trobadorica e del virelai. La melodia sottolinea

l’espressività del testo aiutandone la comprensione. Più tardi, seguendo

l’evoluzione del gusto estetico, essa diverrà più complicata, senza mai

però perdere di vista la funzione primaria del messaggio testuale. La

lauda si sviluppò seguendo due forme: quella lirica semplicemente

cantata e quella drammatica; la diffusione e la pratica di quest’ultima

si deve soprattutto alle confraternite “disciplinate”, a partire dai

primi decenni del XIV secolo.

Il “Laudario di Cortona”, da cui

sono tratte le due laudi proposte nel CD, è uno dei manoscritti più

importanti del Medioevo musicale italiano e fu riscoperto nel 1876; la

prima trascrizione musicale sistematica fu curata da Ferdinando Liuzzi

nel 1935. Il codice, che si fa risalire agli ultimi decenni del XIII

secolo, ci tramanda 44 laudi. Il laudario comincia con le composizioni

dedicate alla Vergine, seguite da altre organizza-te più o meno secondo

il calendario liturgico, con alcune laudi “santorali”. Il Codice

apparteneva alla fraternita di Santa Maria delle Laude che aveva sede

presso la chiesa di San Francesco in Cortona.

Simili alle laudi, solo per l’intenzione devozionale naturalmente, sono i Carols inglesi, che si diffusero tra il 1350 e la metà del XVI secolo. Derivati dalla carole francese, sono canti spirituali che iniziano e terminano con un ritornello, detto burden,

che si alterna alle strofe. Anch’essi molto vicini alla struttura del

virelai e della ballata, nelle forma più antica sono strettamente

connessi al periodo dell’Avvento ed alla celebrazione del Natale.

Pier Maurizio Della Porta

GLORIA ‘N CIELO E PACE ‘N TERRA

Although Easter is the most

important festivity of the Roman Catholic liturgy, in the popular

devotion the liturgical cycle forms an ellipse, the focal points of

which are Christ’s death and resurrection – a fundamental mystery and

dogma in the “History of salvation” – and Christ’s birth, His

incarnation, both being celebrated with equally solemn participation.

Any liturgical innovation introduced in the wake of the music genres

that developed within the more lively cultural centres of each age

regarded, naturally, these most important celebrations. The Orientis

Paribus ensemble here proposes an anthology of music works inspired by

and composed for the festivity of Christmas: some of those which have

become part of the liturgy, as well as others that have been left on the

fringe of it and were used as a commentary to the extra-liturgical

events originated from the popular piety, written in the language of the

people and sung in a style closer to secular music, though still meant

as a complement to the Church’s celebrations. In certain cases these

works were just tolerated by the clergy, while in others they were

well-accepted or even solicited by the Church. The works recorded belong

to a wide geographical and temporal environment: France, England, Spain

and Italy between the 13th and 14th centuries. There are polyphonic tropes and conducti – integral part of the liturgy – and popular votive songs such as carols, cantigas and laudi,

all of which, although dissimilar as far as socio-cultural background

and stylistic structure, stem from the same pious intention of

celebrating the important events of the lives of Christ, the Virgin Mary

and the Saints, moving to devotion, through the stories of such

wondrous happenings, singers and listeners alike.

Sequences and tropes

represented the novelty introduced in a liturgical structure that was

by then well-defined. We shall pass over all questions regarding their

origins, which are still being researched by musicologists, and shall

not attempt any definitions, which, for reasons of brevity, would

necessarily be obscure and incomplete; we wish to mention only the fact

that, after the success of their monophonic forms (between the 9th and

10th centuries), these liturgical songs became the inspiring material

for the first forms of polyphony. The sequence, “new” verses sung over the Alleluja plainsong, can itself be called a trope, although it admits no other melody than that of the Alleluja, over which the prose must be sung. Tropes,

on the other hand, can introduce new verses on a pre-existing

liturgical plainsong or a new melody over the verses of an old

liturgical song, as well as be its prelude or complement, which is the

case of the tropes that have worked their way into the themes of the breviary office. The conductus

asserted itself around the 9th century in the south of France; it is a

vocal composition on a Latin text the music of which – according to the

most credited literature on the subject – was composed ex novo.

The name derives from its liturgical function, which was that of

accompanying the celebrant’s movements and also, more figuratively, of

“leading” to the liturgy’s different moments. With the birth of

polyphony, all these forms were written for more than one voice,

becoming ground for the new cantores’ show of mastery and inspiration, all the way up to the high expressions of the Paris school, the so-called Notre-Dame school, which would have great influence on the musical production of the 13th and early 14th centuries.

The

sources of the pieces proposed by the Orientis Partibus Ensemble in the

present CD, deriving as they are from different geographical areas,

prove the diffusion and endurance of these cultural and musical themes.

The Las Huelgas manuscript for example, composed at the beginning of the

14th century, documents – like the manuscript of the Madrid National

Library (No.20486) – the importance that the teachings of the Notre-Dame

school had in Spain. The manuscript, in fact, contains many pieces

originating from Paris; it also contains less “intricate” polyphonic

compositions, belonging to a period that at the time when the codex was

written was already quite removed, such as the Verbum bonum et suave, dating back to the beginning of the 12th century and witnessing to the persistence in the liturgy of some compositions.

The Ars Antiqua

reached its apex with the assertion of the motet, which, taking on new

and different connotations, would become a genre of transition towards

the Ars Nova.

The motet is based, structurally speaking, on a tenor voice – singing a text taken from the liturgical repertoire, though independent from it – and on two other voices: motetus and triplum, which, in the oldest examples, sang the same text as the tenor,

while later they would be given different, though similar, ones. Later

the motet would put to music also secular texts, of a satirical, amorous

or political subject. The Montpellier manuscript (Faculté de Médecine H

196) is one of the most important sources of this musical genre. Some

authors believe that the motet Alle psallite cum luya (here

proposed in an instrumental version), opening our CD and taken from the

above-mentioned manuscript, witnesses to the trope’s influence on the

first forms of motet, as the two highest voices sing a trope, Psallite cum, which comes between the tenor’s Alle and luya.

The collection of the Cantigas de Santa Maria, dating from a period between 1252 and 1284, is thought to be the work of King Alfonso X el Sabio.

It has come down to us in four manuscripts - three of which in musical

notation – which are some of the most important testimonies documenting

the music, poetry and also miniaturists’ art during the Middle Ages. The

manuscripts consist of more than 400 spiritual compositions on the

miracles of the Virgin Mary, largely inspired by the Miracles de Notre Dame by the trouvère monk Gautier de Coinci. From a structural point of view they are modelled after the French virelai,

with an ABA form, although the variants to that fundamental scheme are

numerous. Still open is the question regarding their musical style and

rhythmical interpretation; some see in them the influence of the Arabian

culture, with regards to both text and music, others reject this

supposition. Indeed, the blending and juxtaposition of elements deriving

from the two different cultures seems historically quite plausible.