Ricercar 322

2012

Claudio MONTEVERDI (1567-1643)

Missa da capella a sei voci*,

fatta sopra il motetto In illo tempore del Gomberti, a 6

1. Kyrie* [3:53]

2. Gloria* [5:59]

3. Salve Regina [II], a 3 [3:59]

(TTB: VD, MBor, MBel)

4. Credo* [10:20]

5. Salve Regina [III], a 3 [4:23]

(TTB: RG, GF, MV)

6. Sanctus* [3:42]

7. Agnus Dei*, a 6 e 7 [5:16]

8. Regina caeli, a 3 [3:30]

(CCA: SF, BZ, GM)

9. Cantate Domino, a 6 [1:54]

Giaches DE WERT (1535- 1596)

10. Fantasia per organo [4:49]

11. Vox in Rama, a 5 [3:36]

12. Ascendente Jesu, a 6 [5:20]

(I pars: AC, SB, CC, GF, FF, DB)

13. Adesto dolori meo, a 6 [3:10]

Nicolas GOMBERT (c.1495-c.1560)

14. In illo tempore loquente Jesu, a 6 [4:45]

Odhecaton

Paolo Da Col

Alessandro Carmignani, Christophe Carré, Stephen Burrows,

Aurelio Schiavoni, Roberto Balconi, Gianluigi Ghiringhelli:

countertenors

Fabio Furnari, Gianluca Ferrarini, Paolo Fanciullacci, Massimo Altieri,

Vincenzo Di Donato, Raffaele Giordani: tenors

Mauro Borgioni: baritone

Matteo Bellotto, Davide Benetti, Marcello Vargetto: basses

Marta Graziolino: harp

Liuwe Tamminga: organ

Federico Bagnasco: violone

Massimo Sartori: bass viol

Michele Pasotti: theorbo

with the participation of

Silvia Frigato, Barbara Zanichelli: sopranos

Gabriella Martellacci: contralto

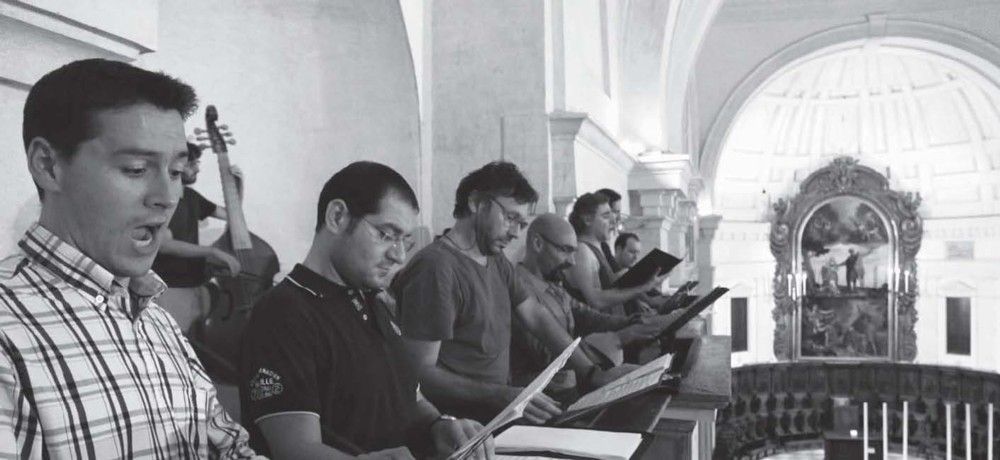

Recorded in September 2011: Mantova, Basilica di Santa Barbara

Artistic direction, recording & editing: Jérôme Lejeune

Sources

#1, 2, 4, 6, 7: Sanctissimae Virgini Missa senis vocibus ad

ecclesiarum choros ac Vesperae pluribus decantandae, Venezia,

Ricciardo Amadino, 1610 (edited by Melita Fontana, Bologna, Ut Orpheus,

2012)

# 3, 5, 8: Salve Regine del Sig. Claudio Monteverde [Venezia,

Alessandro Vincenti, 1662-1667] (edited by Luigi Collarile, Bologna,

Arnaldo Forni, 2011)

#9: Giulio Cesare Bianchi, Libro secondo de motetti in lode della

gloriosissima Vergine Maria Nostra Signora, Venezia, Alessandro

Vincenti, 1620

#10: Fantasia di Giaches, Roma, Biblioteca Vaticana, ms. Chigi

VIII 206

#11: Il secondo libro de motetti a cinque voci, Venezia, Erede

di Girolamo Scotto, 1581

#12: Modulationum cum sex vocibus liber primus, Venezia, Erede

di Girolamo Scotto, 1581

#13: Motectorum quinque vocum liber primus, Venezia, Claudio

Merulo e Fausto Betanio, 1566

#14: Motetti del frutto a

sei voci, Venezia, Antonio Gardano, 1539

(11-14: transcriptions by Renzo Bez)

MUSIC AND DEVOTION AT THE

GONZAGA COURT: CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI AND GIACHES DE WERT

The lives of the two composers whose music makes up the major part of

this recording overlapped in the 1590s, when both were in the service

of the Gonzaga family in Mantua. Moreover, the music presented here was

almost certainly originally written for the same remarkable

institution, the Palatine Basilica of Santa Barbara, which had been

constructed over a ten-year period beginning in the late 1560s. This

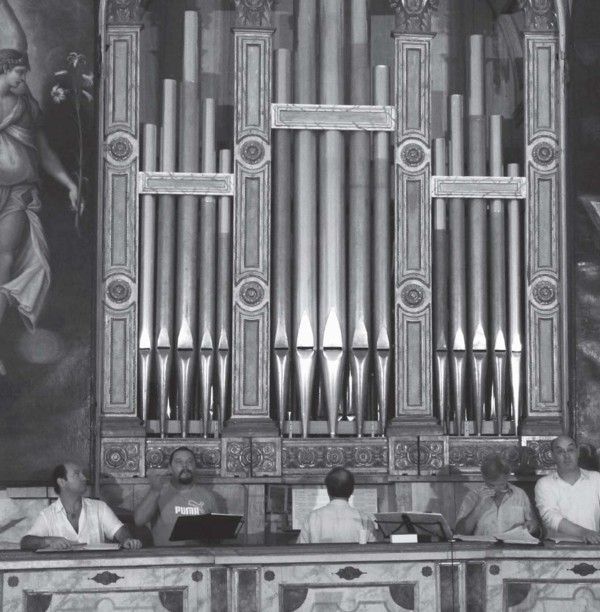

recording was made inside this church, using not only the West gallery

(mentioned by contemporaries as being used by the musicians of the cappella),

but also the two cantorie which stand halfway down the nave, in

one of which is preserved the organ constructed by Costanzo Antegnati

in 1565. The Basilica had been planned from the start as a kind of

dynastic temple, a theatre for Gonzaga politico-dynastic ceremonies, as

well as a highly individual interpretation of Catholic reformist

attitudes towards sacred art. Its special character, expressed through

extraordinary papal privileges, which included permission to draw up

its own rite, and the provision of prestigious positions for its

clergy, automatically conferred upon Santa Barbara a status which made

it the envy of other Italian princes. The role of the Duke of Mantua,

Guglielmo Gonzaga, a pious and careful ruler keen to project an image

of himself as the True Christian Prince, was central to this

development; the construction and operations of the Basilica, and

especially the evolution and performance of its substantial musical

repertory (conserved virtually complete in the Conservatory in Milan),

occupied him almost to the point of obsession.

Giaches de Wert, who was born in Flanders, arrived in Mantua to take up

the post of maestro di cappella of Guglielmo Gonzaga’s

new Basilica in 1565, and he was to remain there until his death some

decades later. Although much of his time in Mantua was occupied with

writing madrigals (he was to publish no fewer than eight books in the

genre during these years), his main duties as maestro required

him to be in charge of the composition and performance of liturgical

music. Nonetheless, he composed only a modest amount of sacred works

himself, including just three published books of motets, two for five

voices and the third one for six. The high point of the second book of

1581 is undoubtedly Vox in Rama, a setting of a text taken from

the Book of Jeremiah which is also quoted in St. Matthew’s

Gospel. This describes, in plangent and moving language, the sense of

desolation experienced by a mother over the loss of her children. It

begins with a stark opening motif in the low tessitura of each voice,

followed by a dramatic rising octave leap. This sets the tone for the

rest of the piece, which exploits to the full many techniques that are

more characteristic of Wert’s madrigals. Equally dramatic is Ascendente

Jesu, which first appeared in the Modulationum cum sex vocibus

liber primus, also published in 1581. As Wert himself acknowledged

in a letter of March 1579, this presents considerable difficulties for

the singers at the words ‘ecce motus magnus factus est in

mari, ita ut navicula operiretur fluctibus’, words which

prompted him to respond with an extended passage full of syncopations

and cross rhythms which occur in different voices at different times.

In what is an extremely rare example of a contemporary comment by a

composer about his own music, Wert makes a plea for artistic licence;

should all not go well, he writes, it is the fault of the performers

and not the composer. More restrained in style is Adesto dolori meo,

printed in 1566, and conceivably composed before Wert took up his post

in Mantua. Largely through Gonzaga influence, he had previously served

the Spanish Governor in Milan (where members of the Gonzaga held

powerful military positions), and before that the Gonzaga of Novellara,

a cadet branch of the family which governed a small court located in

the Po valley. In other words, Wert was a good company man whose

fortunes were inextricably linked to Gonzaga patronage. This provided

him with stability and employment throughout his entire career, from

his arrival in Novellara in about 1551 until his death in Mantua in

1596.

Claudio Monteverdi’s relations to the Gonzaga were more

complicated. From Cremona, where he had been born in 1567, Monteverdi

arrived in Mantua in about 1590, initially to take up service as an

instrumentalist at court. Despite his steady output of madrigals, not

to mention the composition of L’Orfeo, L’Arianna,

and the Ballo dell’Ingrate for performance at court in

1607-8, he was never appointed as maestro at Santa Barbara, and when

the post fell vacant in 1609, Monteverdi was passed over. That may have

been partly due to his profile as a composer. It was now some

twenty-seven years since he had published any sacred music, and even

that, the juvenile Sacrae cantiunculae of 1582, written during

his apprenticeship in Cremona, does not include any settings of

liturgical texts. It might well have been this lacuna that now prompted

him to embark on an ambitious and unusual plan to publish the

large-scale collection of fifteen pieces which has come to be known as

the Mass and Vespers of 1610. The two liturgical halves of this

publication are also stylistically contrasted. Whereas the Vespers

music includes a number of solo motets in the latest virtuoso song

style, the Mass setting is altogether more conservative in style, and

was perhaps Monteverdi’s response to the attacks that had

recently been launched upon his music by the Bolognese theorist,

Giovanni Maria Artusi, the last of which had appeared in print only two

years previously. Certainly the Mass sets out to demonstrate

Monteverdi’s complete technical mastery of the prima prattica

manner, being cast in a dense, imitative texture based on motifs taken

from the motet In illo tempore composed by the Flemish composer

Nicolas Gombert more than seventy years earlier. Artusi apart, the

decision to adopt the prima prattica manner is not that

uncommon among contemporary composers, notwithstanding the discernible

shift to the concertato style in North Italian church music.

Since the greater part of the liturgical texts of the Mass are

essentially neutral in character, the older style possessed both the

capacity to render these effectively as well as evoking the hallowed

status of tradition. Another feature of Monteverdi’s choice may

well have been the influence of his teacher Marc’Antonio

Ingegneri (with whom he had studied in Cremona in the 1580s), whose

music largely avoids the recent homophonic style advanced by Andrea

Gabrieli and other members of the Venetian school, in preference for

flowing polyphony.

Since, as the title-page declares, both Vespers and Mass are addressed

not only to the Virgin but also to Pope Paul V, the entire publication

effectively carries a double dedication. In the case of the Virgin this

was appropriate not only as a response to the notable increase in

Marian devotion characteristic of the period, but also because Mary was

venerated as a protector and patroness of both the city of Mantua and

of its rulers. On the other hand, the more immediate relevance of the

Papal dedication becomes clear from Monteverdi’s subsequent

actions. Later in the same year the composer travelled to Rome to

present a copy of the Mass and Vespers to the Pope, partly it seems in

the hope (which in the event turned out to be in vain), of obtaining a

place in the Seminario Romano for his son, Francesco. Conscious

perhaps of his deteriorating relationship with the Gonzaga (his letters

from these years are shot through with complaints of hardship and

overwork), it may be that Monteverdi was also laying the groundwork for

an attempt to find a post in Rome itself, by demonstrating his complete

mastery of the whole range of current styles of sacred music, including

Netherlandish polyphony.

Although the Missa In illo tempore is one of just three

complete settings by Monteverdi that are known, he must have composed

many more if we are to believe his statement, made in a letter of

February 1634, that he was required to write a new setting of the

Ordinary every year for performance in St. Mark’s Basilica on

Christmas Eve. The other two surviving settings, both of which were

probably written during his Venetian years, also rely upon the

restrained a cappella style of the second half of the sixteenth

century which, by the time that they were written, had become known as

the stile antico (the old style). In effect, all three of

Monteverdi’s masses are highly wrought exercises in a form of

conscious antiquarianism that not only demonstrate Monteverdi’s

command of traditional techniques, but also stand in stark contrast to

much of the church music that was then being written, including much of

that composed by Monteverdi himself. The 1610 Mass quite consciously

recalls an even more archaic contrapuntal language; shaped by the

motifs taken from Gombert’s motet, which are frequently given

prominence, it displays the rigid adherence to a tautly-constructed

imitative texture that is characteristic of many works of the

post-Josquin generation. In pursuit of this goal Monteverdi has

recourse to an armoury of contrapuntal complexities, including

paraphrase, countersubjects, invertible counterpoint, inversion,

retrogression, augmentation, and canon. Prominent too is the use of

sequence, which recalls the music of Josquin himself, who deployed the

technique to great effect in the search for symmetry, as in the Missa

L’homme armé sexti toni. This device produces some of

the clearest moments of articulation in Monteverdi’s mass. The

relentless imitative texture is relieved by homophony on just two

occasions, with the Et incarnatus est section of the Credo, and

throughout the Benedictus. Both of these begin on a bright E major

triad, in distinct contrast to the long surrounding passages in the

Ionian mode (in which most of the Mass is written), with the effect of

expressively illuminating the concept of the Incarnation itself.

Despite (or perhaps because of) its radically conservative character,

the Missa In illo tempore was still being performed in the

Sistine Chapel as late as the eighteenth century.

A high point of the present recording is the inclusion of three

previously unknown works by Monteverdi, recently identified by the

Italian musicologist Luigi Collarile. Two of these are settings of the

Marian antiphon Salve Regina, while a third takes as its text

the Easter antiphon Regina Caeli. All three, which are scored

for different combinations of three voices with organ accompaniment,

have lain unnoticed (though to some extent disguised) in the only

surviving copy of a collection of sacred music printed by the Venetian

printer Alessandro Vincenti in the 1660s, some twenty years after

Monteverdi’s death. It may well have been Francesco Monteverdi

who was responsible for arranging the publication of his father’s

music by Vincenti, who also printed a number of other posthumous works

during the 1650s. Such pieces were multi-purpose, since they could have

been performed by Monteverdi and three singers on any Marian feast in

the Church year. There can be little doubt about the authenticity of

these three new identifications – all three pieces demonstrate

Monteverdian fingerprints on every page. Highly characteristic uses of

affective chromaticism, staccato dotted rhythms and declamatory

passages, and the oscillation between duple and triple time are just

three of the elements that speak eloquently of Monteverdi’s

authorship. The inclusion of all three, recorded here for the first

time, is testimony to the happy marriage of scholarship and practical

musicianship that is characteristic of the work of Odhecaton.

IAIN FENLON

Sur les pas de Monteverdi

Réaliser un enregistrement dans ce lieu mythique fut pour moi

à la fois un moment émouvant et un instant de

réflexion – voire de doute – sur tous les principes

de base de la prise de son. L’émotion d’abord.

Même si Monteverdi ne fut pas responsable de la musique de la

chapelle au service du duc de Gonzague (il y fut engagé

d’abord comme violiste), on ne peut douter qu’il n’a

pas, au titre de compositeur, ou à celui

d’interprète, participé à la musique des

offices de la chapelle. Certaines de ses plus importantes compositions

religieuses (dont celles du recueil de 1610) ont été

écrites durant sa période mantouane. Il est donc probable

que c’est dans cet édifi ce que quelques-uns de ses

chefs-d’œuvre ont résonné pour la

première fois. Et, en les écrivant, pensait-il à

la disposition des différentes tribunes?

L’escalier qui conduit à la tribune de gauche, celle qui

fait face à la tribune d’orgue, est celui que les pieds de

Monteverdi ont foulé il y a plus de quatre siècles.

Marcher dans ses pas fut pour moi d'une émotion incroyable. Ma

réflexion sur le son fut immédiate. Ne fallait-il pas

aussi dans l’enregistrement qui allait être

réalisé tenter de retrouver le miracle sonore de la

basilique avec ses qualités propres, ses particularités?

Or, il se fait que le volume sonore de l’édifi ce est

très ample, la réverbération, sans être trop

grande, est malgré tout importante. Devais-je me mettre à

la place de l’auditeur du XXIe siècle, confortablement

installé devant sa chaîne hi-fi et épiant tous les

détails de la partition? Ou, au contraire, fallait-il

m’imaginer à la place du duc et de ses proches dans la

petite loge qui se trouve à gauche du chœur, ou tout

simplement au centre de l’église, là d

’où l’on peut entendre la musique venant des deux

tribunes latérales de la nef centrale, ou de la grande cantorie

du fond de l’église, elle-même flanquée de

deux tribunes latérales?

Lorsque l’on est au centre de l’église, le son qui

provient des diverses tribunes est très ample; il

bénéficie de la réverbération du lieu, mais

transmet tous les détails avec une incroyable précision.

Hélas!, nos micros n’ont pas l’intelligence de nos

oreilles. Mais, les conditions exceptionnelles du lieu m’ont

convaincu qu’il ne fallait pas vouloir reproduire le son

standardisé de bon nombre d’enregistrements où

l’on cherche à la fois la proximité et ce

qu’il faut d’ambiance générale pour faire

fusionner tous les timbres des instruments et des chanteurs et

reconstituer plus ou moins l’acoustique du lieu.

Il eût été simple de mettre tous les musiciens au

centre de l’église ou dans le chœur, de trouver une

disposition optimale pour satisfaire à une implantation de

micros classique et obtenir un son qui corresponde aux habitudes

actuelles. Mais, ici, la disposition dans les lieux

«originaux» a imposé des choix différents.

Utilisant l’orgue Antegnati (celui que Monteverdi a entendu), la Missa

in illo tempore et le motet Cantate Domino ont

été enregistrés depuis les deux tribunes de la nef

centrale. L’idée de départ était de mettre

tous les chanteurs dans la tribune qui fait face à

l’orgue. D’une part ils y étaient un peu à

l’étroit et d’autre part le son semblait

collé contre le mur. L’idée fut alors de

répartir les chanteurs entre les deux tribunes. Quelle ne fut

pas la surprise de se rendre compte que d’une tribune à

l’autre les chanteurs s’entendaient parfaitement et

pouvaient chanter ensemble sans être perturbés par le

moindre retard venant des chantres de la tribune opposée! La

portion de voûte qui relie les deux tribunes avait

été évidemment pensée pour que la

transmission du son soit optimale entre elles.

Du coup, pour ce qui était de l’enregistrement, les micros

placés au centre de la nef donnaient une image sonore pleine,

équilibrée et finalement assez précise. La

répartition des voix apparaît clairement à

l’audition (ce que l’on peut aisément percevoir par

exemple avec les deux voix de dessus réparties entre les deux

tribunes). Alors que dans l’église, la harpe et le violone

qui se trouvaient dans la petite alcôve derrière les

chanteurs de la tribune de gauche étaient très nettement

perceptibles, il fut nécessaire de leur donner un petit micro

d’appoint.

La cantorie du fond de l’église fut

utilisée pour les trois motets inédits avec basse

continue et pour les motets a capella sans orgue. Cette tribune est

beaucoup plus spacieuse que les tribunes étroites de la nef.

Elle permet plus facilement la disposition de chanteurs et

d’instruments. On y imagine assez facilement le lieu pour les

pièces les plus développées, telles la Sonata

des Vespro, supposant que le cantus firmus viendrait de

l’une des tribunes de la nef! Ici, il a fallu trouver une

association entre des micros qui assuraient une certaine

précision de la perception des chanteurs et des instruments et

d’autres qui restituaient l’acoustique du lieu, a fin de

retrouver ce miracle que l’on découvre, installé

quasi n’importe où dans l’église.

JÉRÔME LEJEUNE