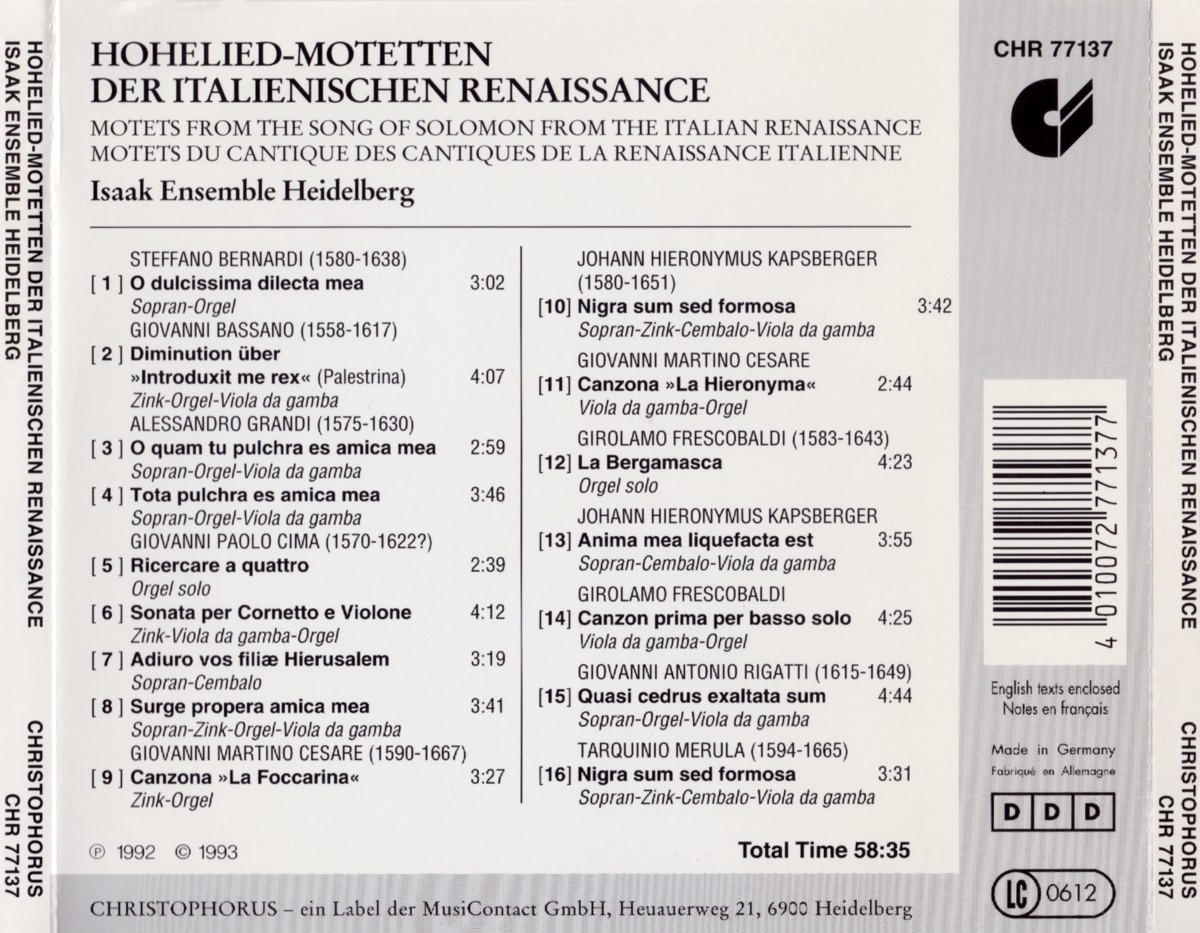

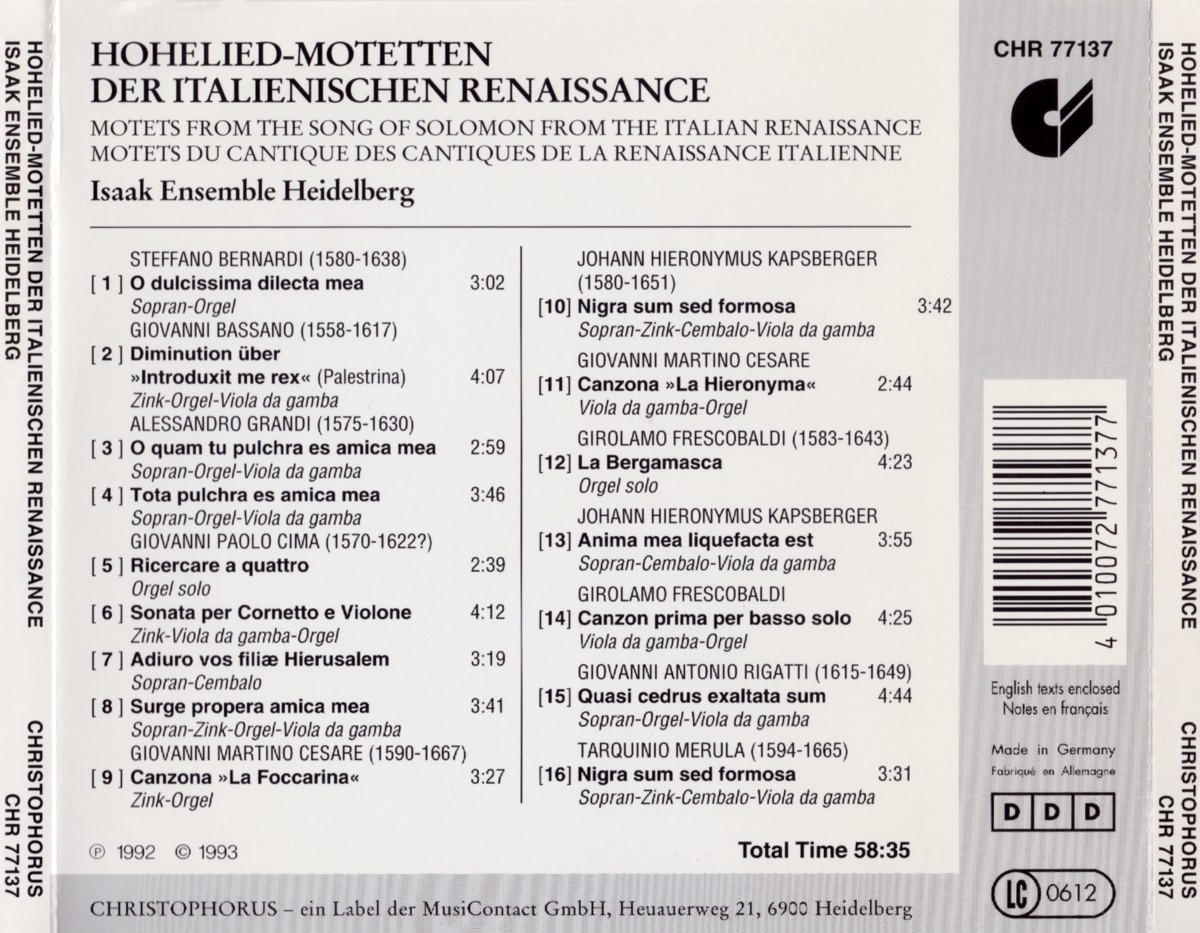

Hohelied-Motetten der italienische Renaissance

/ Isaak Ensemble Heidelberg

Motets from the Song of Solomon from the Italian Renaissance

Christophorus CHR 77137

1993

[58:35]

STEFFANO BERNARDI (1580-1638)

1. O dulcissima dilecta mea [3:02]

Sopran – Orgel

aus: Seconda raccolta de sacri canti (Venedig 1624)

GIOVANNI BASSANO (1558-1617)

2. Diminution über »lntroduxit me rex“

(Palestrina) [4:07]

Zink – Orgel – Viola da gamba

aus: Motetti madrigali et canzone francese (Venedig 1591)

ALESSANDRO GRANDI (1575-1630)

3. Oquam tu pulchra es amica mea [2:59]

Sopran – Orgel – Viola da gamba

aus: Ghirlande sacre scelta (Venedig 1625)

4. Tota pulchra es amica mea [3:46]

Sopran – Orgel – Viola da gamba

aus: Motetti a voce sola (Venedig 1621)

GIOVANNI PAOLO CIMA (1570-1622?)

5. Ricercare a quattro [2:39]

Orgel solo

aus: Regula del contrapunte (Mailand 1622)

6. Sonata per Cornetto e Violone [4:12]

Zink – Viola da gamba – Orgel

7. Adiuro vos filiae Hierusalem [3:19]

Sopran – Cembalo

8. Surge propera arnica mea [3:41]

Sopran – Zink – Orgel – Viola da gamba

aus: Concerti ecclesiastici (Mailand 1610)

GIOVANNI MARTINO CESARE (1590-1667)

9. Canzona »La Foccarina“ [3:27]

Zink – Orgel

aus: Musicali melodie (München 1621)

JOHANN HIERONYMUS KAPSBERGER (1580-1651)

10. Nigra sum sed formosa [3:42]

Sopran – Zink – Cembalo – Viola da gamba

aus: Libro primo di motetti passegiati (Rom 1612)

GIOVANNI MARTINO CESARE

11. Canzona »La Hieronyma“ [2:44]

Viola da gamba – Orgel

aus: Musicali melodie (München 1621)

GIROLAMO FRESCOBALDI (1583-1643)

12. La Bergamasca [4:23]

Orgel solo

aus: Fiori Musicalo (Venedig 1635)

JOHANN HIERONYMUS KAPSBERGER

13. Anima mea liquefacta est [3:55]

Sopran – Cembalo – Viola da gamba

aus: Libro primo di motetti passegiati (Rom 1612)

GIROLAMO FRESCOBALDI

14. Canzon prima per basso solo [4:25

Viola da gamba – Orgel

aus: Canzoni da sonare, libro primo (Venedig 1621)

GIOVANNI ANTONIO RIGATTI (1615-1649)

15. Quasi cedrus exaltata sum [4:44]

Sopran – Orgel – Viola da gamba

aus: Motetti a voce sola (Venedig 16431)

TARQUINIO MERULA (1594-1665)

16. Nigra sum sed formosa [3:31]

Sopran – Zink – Cembalo – Viola da gamba

aus: Motetti e sonate, libro primo (Venedig 1624)

Eva Schildknecht, Petra Manz-Bauer, Arno Paduch, Andreas Großmann, Eva Lebherz-Valentin

Photo: Braun, Ottobeuren

AUSFÜHRENDE / PERFORMERS

Isaak Ensemble Heidelberg

Eva LEBHERZ-VALENTIN — Sopran / soprano

Arno PADUCH — Zink / cornett

Petra MANZ-BAUER — Viola da gamba / viol

Andreas GROSSMANN — Truhenorgel / chest organ

Eva SCHILDKNECHT — Cembalo / harpsichord

INSTRUMENTE / INSTRUMENTS

Truhenorgel / chest organ

nach oberitalienischem Vorbild

Heidelberger Cembalobau 1992

Gedackt 8', Flöte 4', Prinzipal 2'

alle Register aus Zypressenholz

(C - transponierbar a = 440/415 Hz)

Truhenorgel / chest organ (nur [12] Frescobaldi: La Bergamasca)

Freie Nachbildung der Truhenorgel von Gottlieb Näser, Posen 1734

Orgelbau Rohlf, Neubulach

Temperierung nach Neidhardt, mit 6 reinen Quinten

Gedackt 8' (Eiche), Flöte 4' (Birnbaum, als Rohrflöte),

Octave 2' (Zinn, kontra H bis Fis Eiche), Nasard 2 2/3' ab c/cis (kontra H bis f3, mit Transponiereinrichtung)

Cembalo / harpsichord

Italienisches Instrument nach Ferrini

Heidelberger Cembalobau

8', 8', Lautenzug

(C - d''' transponierbar a = 440/415 Hz)

Aufnahme / Recording: 4.-6.6.1992, Kaisersaal Benediktinerabtei Ottobeuren

Aufnahmeleiter / Producer: Dietmar Will

Tonmeister / Balance Engineer: Dietmar Will

Redaktion / Booklet Editing: Manfred Glaser

Übersetzungen / Translations (English): • Karl F. Wieneke / Rebecca Reese

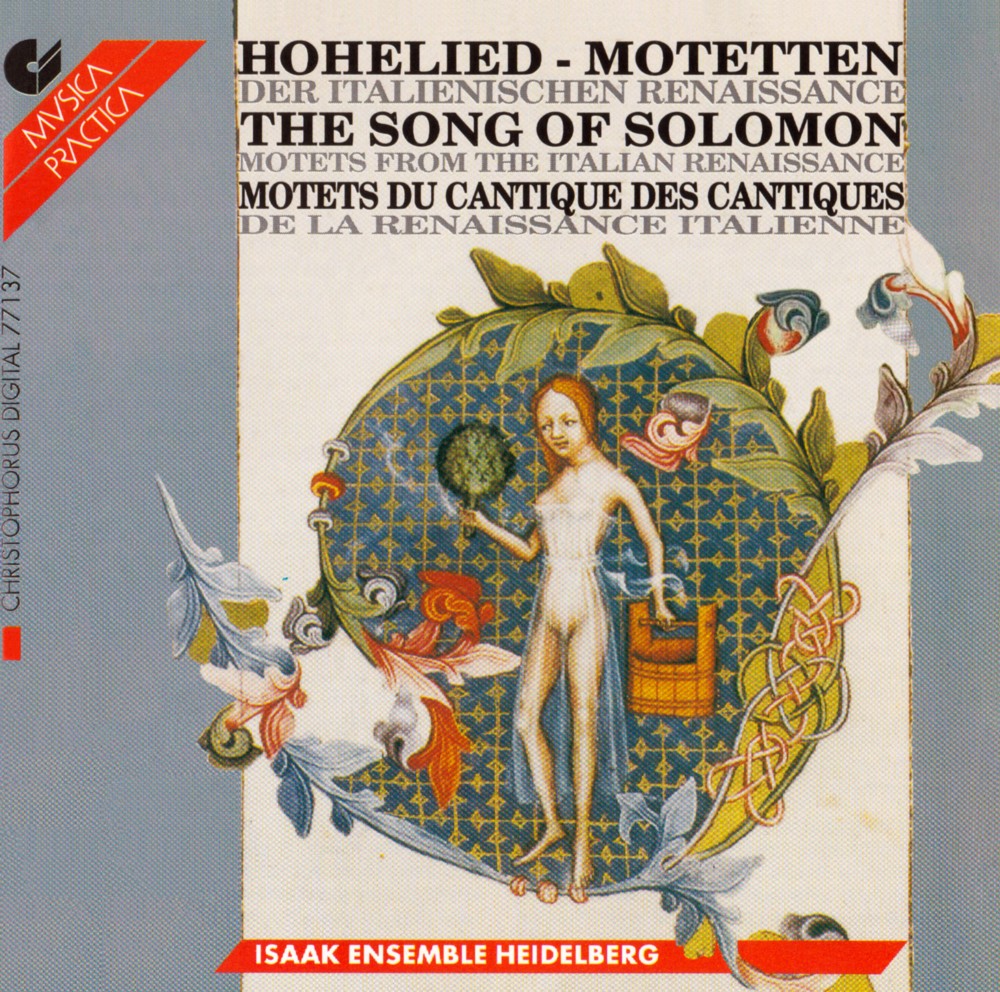

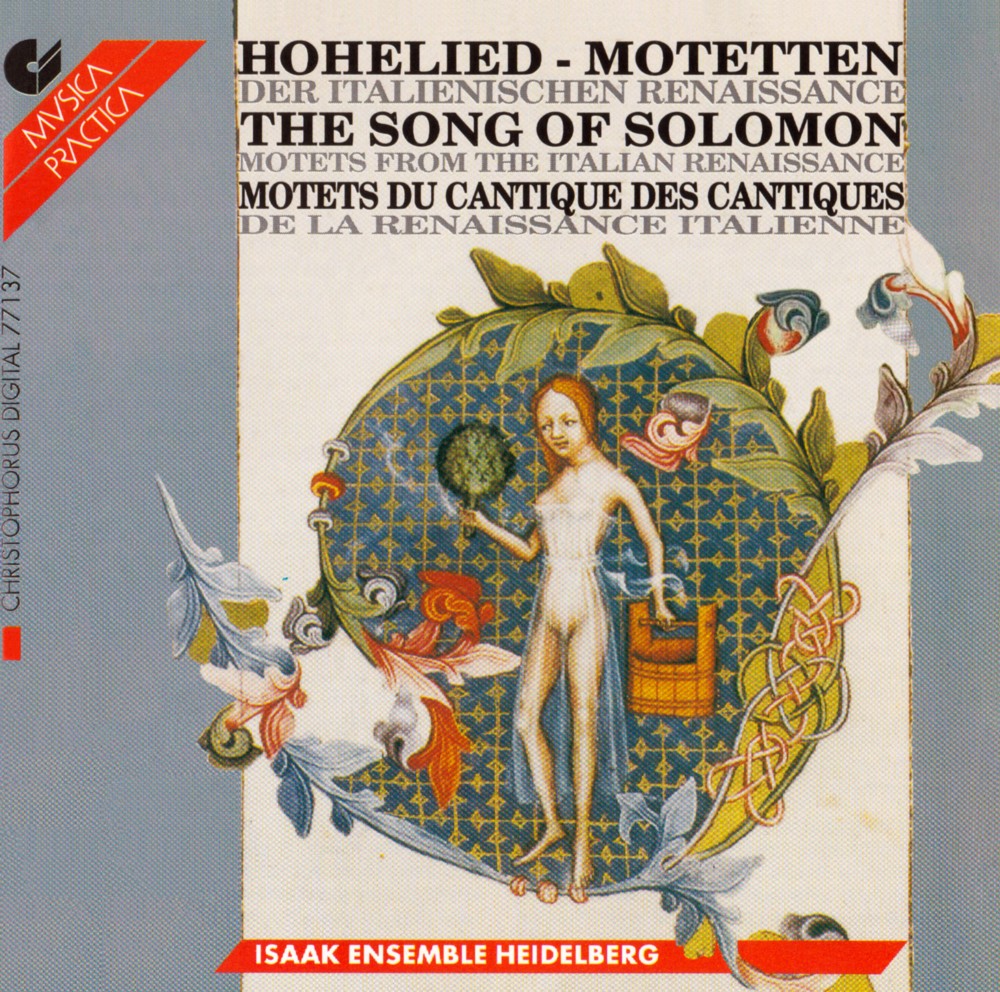

Titelbild / Cover Picture:

Bademädchen aus der Wenzelsbibel, Codex Vindobonensis 2759 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien)

Titelgestaltung / Cover Design: Manfred Glaser

℗ 1992 © 1993 MusiContact GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany

THE SONG OF SOLOMON

AN ENCOUNTER WITH A BIBLICAL PROVOCATION

by Detmar Huchting

A provoking question shall be put at the beginning of these thoughts:

How did erotic literature become part of the bible, or what is the

function of this chapter in the Book of Books, which neither tells

about God nor about the relationship between God and man, and which in

no way shows any religious character?

A Rabbi of the first century answered: "A book of such beauty can only

derive from God!" and that proved to be a grave argument in the debate

at the end of which the Song of Solomon became part of the Jewish Bible

under the name of Schîr haschrîrîm aschär le-Schelômô

(song of songs which stems from Solomon).

Looking back into history, we find that the Song of Solomon did not

first appear in King Salomo's time and certainly he was not the author.

It is a collection from different sources and was published under his

name. For Israel this King represented the time of its greatest power

and glory.

Recalling the historical schedule we find that in the 3rd and 4th

century b.c. a book of poems was compiled (it is difficult to date the

single parts exactly), which another three or four hundred years later

eventually became part of the scripture. This long period of time also

represents the complex cultural context in which the Song of Solomon

was written: its roots reaching back as far as Old Egyptian lyrics, the

book got its final shape when Near East was, politically as well as

culturally, dominated by the Hellenistic Kingdoms of Alexander the

Great's successors. Eventually, it found its way into the Bible while

the 'world' was under Roman government.

Together with the Old Testament Christianism inherited the Song of Solomon

as part of the Jewish Bible, and with it inherited the

difficulties to have to interpret the book as Word of God.

The history of the Song of Solomon

is a history of ethical views changing with time. An uninhibited

perception of man not dividing body and soul prevailed in the Ancient

Orient where some of the poems were written. The book was compiled

during the Hellenistic era when Greek philosophy merged with the old

culture of the region. Just before the change of times it became part

of the holy scriptures; Jewish sects, slightly later, imposed their

ideal of chastity upon the Christian daughter, the world's dominating

religion to come.

It was most obvious to interpret the loving relationship allegorically

as the relationship between God and his people Israel, likewise as that

of God and the Blessed Virgin or the one between Jesus and His Church.

It should be mentioned in this context that St.Bernard de Clairvaux -

generally not known as a friend of the Jews - recognises two lovers of

the Lord: the fair-skinned friend is the Church, the dark-skinned one

is the Synagogue.

In recent times, the methods of historical criticism throw new light

upon the interpretation: while people always recognised the role of

physical love in the Song of Solomon,

employing these methods gave way to the interpretation as a purely

human loving relationship without having to expell the Song of Solomon from the Holy Scriptures.

The different view of our days concerning the human body and its

sexuality allow for new messages, which work in a freeing and enriching

way:

1. Certainly is love different in its appearences, but renunciation of

loving partnership and sexuality does not by itself lead closer to God.

2. By means of love, erotic and partnership, as they are described in

the Song of Solomon, men and women anew recreate the likeness of

mankind and the God above all antagonism of sexes: both male and female

together are "man" as God created them "in our image, after our

likeness". With their care for each other mankind perfect one another

to become what their Creator had meant them to be.

Furthermore, this interpretation of the Song of Solomon

can overcome the polarity of sexes and become a praise of "Love" in

general. As this way of interpreting is allegorical again it would

probably not remain uncontradicted by modern theologists. The Song of

Solomon can like other biblical words be interpreted in many a way, and

possibly this is one of the characteristics of the Word of God. The

expressiveness of the human language is not enough to carry a message

of such importance. So the word-settings gained a special importance,

as music maybe is the art which comes closer to divine truth than the

spoken word.

THE PROGRAM

The text was especially popular among seventeenth-century composers.

The clear separation between sacred and secular music that we know

today did not then exist, and a text which speaks so eloquently of

longing and desire offered composers the opportunity to bring the

expressive devices of opera and madrigals into the Church.

Chromaticism, dissonance, text declamation and, to some degree, abrupt

changes of key were used to set the texts in a way that moves us still

today.

Our selection of settings is limited to composers who either were

Italian or who were employed in Italy. In the course of the Counter

Reformation, Marian devotion reached its high point, especially in

Italy. It is therefore not surprising that the best-known work in honor

of the Virgin Mary, Claudio Monteverdi's Marian Vespers, contains in

addition to Psalm settings, pieces whose texts are not part of the

liturgy proper, but which could have served in place of the repetition

of the antiphon. That some of these texts are taken from the Song of Solomon comes also as no surprise. The pieces we have selected could have served a similar liturgical function.

Alessandro Grandi held various positions as singer and maestro di capella in Ferrara and Venice until he was elected maestro di capella at Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo in 1627. Grandi died of the plague in 1630.

The following year his successor, Tarquinio Merula,

was charged with reviving the capella at the cathedral. In addition,

Merula worked in Cremona, and served as organist for some years at the

Polish court in Warsaw.

Until well into the eighteenth century, musicians were expected to be

able to improvise embellishments spontaneously during the performance

of a piece. In 1591, Giovanni Bassano,

cornettist at San Marco in Venice, published a collection of over fifty

such written-out "improvisations" on motets and madrigals of the

sixteenth century. The diminution on Introduxit me rex

by Palestrina is taken from this collection. In the early seventeenth

century, composers began writing works with diminutions as an integral

part of the composition.

One collection of such ornamented motets was published in 1612 by

Johann Hieronymus Kapsberger,

a German who spent his early years in Italy and who is best-known for

his lute compositions. We have chosen two motets from the collection.

Steffano Bernardi was born in

Verona where he worked for several years at the cathedral. In 1622 he

left Verona to join the services of the bishop of Breslau and Brixen,

Archduke Carl Joseph. But soon, in 1624 the bishop died and his chapel

was dissolved. Bernardi was called to Salzburg, where he stayed until

he died of the plague in 1638.

Giovanni Paulo Cima was employed as organist at San Celso in Milan. He included several instrumental pieces in his collection Concerti ecclesiastici, among them the Sonata per Cometto e Violone.

Giovanni Antonio Rigatti became maestro di capella

at the cathedral in Udine at the age of twenty. Later, he returned home

to Venice and was a singer at San Marco. In 1646 he described himself

as maestro di capella for the patriarchs of Venice. He also taught singing at the Conservatorio degli lncurabili, in whose church he was buried in 1649.

Giovanni Martino Cesare was

born in Udine, where he also worked for a time as a cornettist. From

1611 he was active in Germany, first in Günzburg and, after 1615,

at the court chapel in Munich. Although he himself offered his services

to Count Ernst von Bückeburg, Cesare did not appear on St.Michaels

Day 1617, when he should have begun the appointment, his reason being,

he could not with a clear conscience serve at a Lutheran court.

Girolamo Frescobaldi was born

and received his early musical training in Ferrara. In 1604 he went as

a singer and organist to Rome where he became a member of the Congregazione ed Accademia di Santa Cecilia.

He was chosen as organist at San Pietro in 1608, a position he held,

despite interruptions in service, until his death in 1643.

Arno Paduch