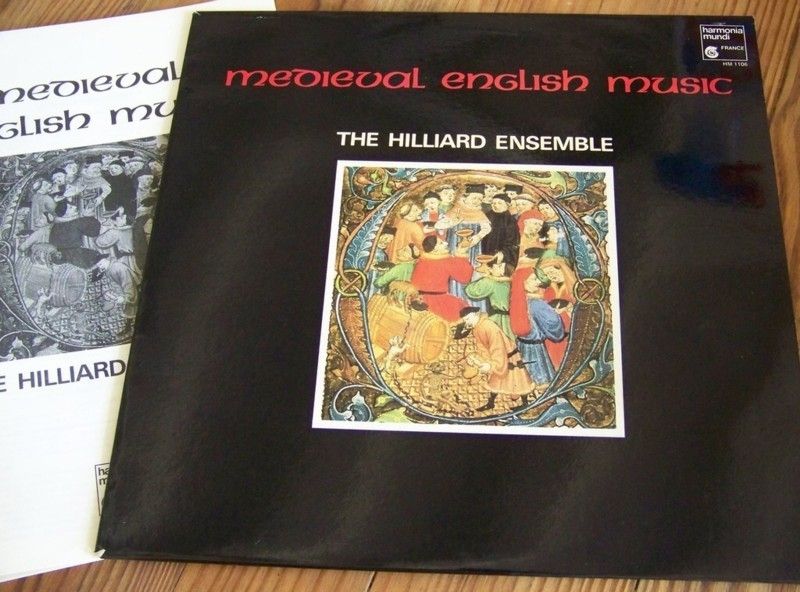

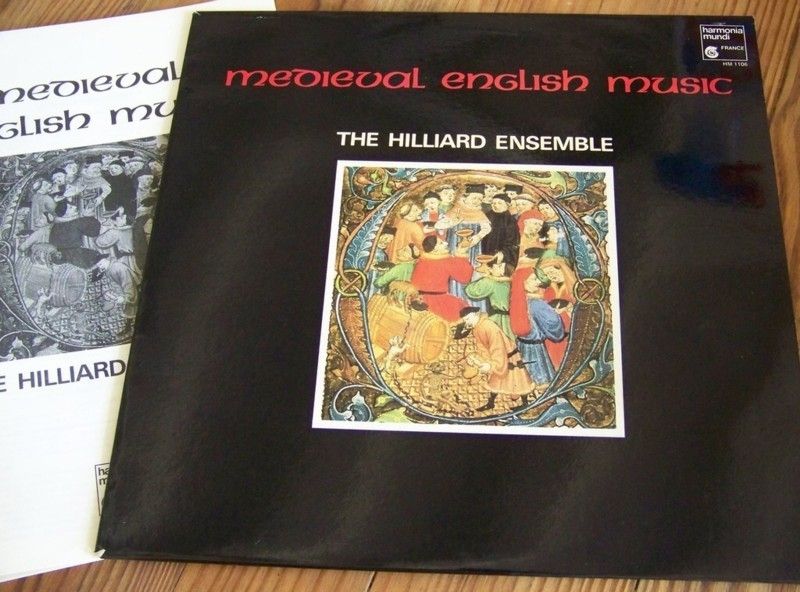

Medieval English Music / The Hilliard Ensemble

medieval.org

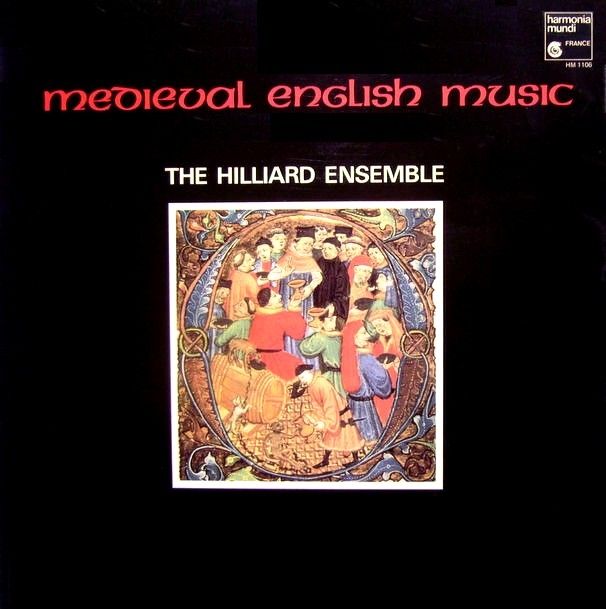

Harmonia Mundi HMC 1106 (LP)

CDs:

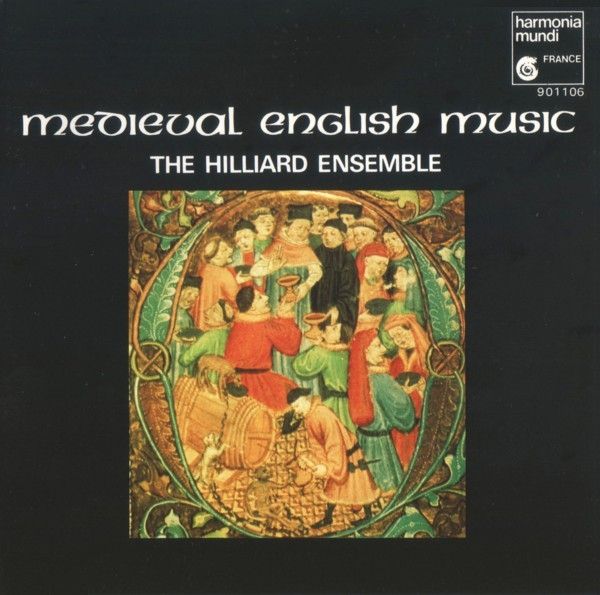

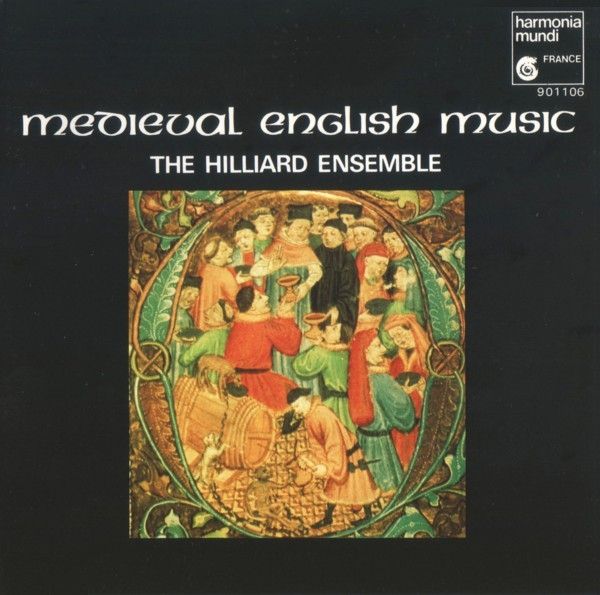

Harmonia Mundi HMC 901 106

Harmonia Mundi "musique d'abord" HMA 190 1106

Harmonia Mundi "Classical Express" HCX 395 1106

Harmonia Mundi "musique d'abord" HMA 195 1106

1983

XIVe siècle

1. Alleluia. Hic est vere martir [4:01]

2. Singularis laudis digna [5:36]

3. Doleo super te [1:33]

4. Thomas gemma Cantuarie [2:23]

5. Civitas nusquam conditur [2:25]

6. Tu civium primas [2:41]

7. Mater Christi nobilis [1:33]

8. Ite missa est [1:30]

XVe siècle

9. Alleluia. A newe work [3:47]

10. John PLUMMER. Anna Mater Matris Christi [6:01]

11. There is no rose [3:50]

12. Tota pulcra es amica mea [4:08]

13. Marvel not, Joseph [8:18]

14. O potores exquisiti [4:18]

THE HILLIARD ENSEMBLE

Ashley Stafford, countertenor

Paul Elliot, tenor

Rogers Covey-Crump, tenor

Leigh Nixon, tenor

Paul Hillier, bass

harmonia mundi Ⓟ 1983

Enregistrament septembre 1982

Prise de son Jean-François Pontefract

Assistance musicale Marcel Frémiot

Illustration: Miniature, "O potores" / British Museum BM Egerton 3307

The Fourteenth Century

The 14th century was an age of «modern music». So, in a

sense, is every age; but like ourselves today, people in the 14th

century were aware that things were new.

Musicians were conscious of creating a new art. For this period as a

whole, music historians have been content to retain the name «Ars

Nova» used by the French theorist and composer Philippe de Vitry

as the title for his treatise around the year 1320.

The essence of this newness lay in rhythm - or, rather, in the

development of a system ofnotation that encouraged the combination of

many different lengths and subdivisions of notes. Thus grew up a

particular musical style, a refinement that became inereasingly

mannered as the century grew old, but wbich found its finest expression

in the music of Guillaume de Machaut and, in Italy, Francesco Landini.

England

Since the Norman Conquest in 1066, English culture had been dominated

by French influences, nevertheless, medieval English literature

maintained its vernacular core onto which Chaucer successfully grafted

the French inheritance (taking not a little inspiration from Italian

literary forms). Similarly, towards the end of the 14th century,

Englisb music had evolved a style that could draw upon a mixed heritage

from England and France (and some ideas from Italy), moulding them

together into a national style that was admired abroad as «La

Contenance Angloise».

Despite the scant remains, it is possible lo build up a reasonable

picture of English music in the 14th century and even to point to some

of its dominant characteristics. These are found above all in two

frequently used techniques: the parallel movement in chords known as

Descant, and the repeat or answering exchange of words and melody

between one singer and another as found in Rondellus.

In maintaining a preference for chordal sonorities, even in pieces that

apply the rondelus tecbnique (such as «Thomas gemma>), and in

being slow to adopt the isorhythmic motet style so prevalent on the

continent, English composers were being more than just typically

conservative. The works in tbe first half of this record show that a

somewhat separate development took place in this country. In

particular, the fuller sound favoured by the descant style formed an

important aspect of the Old Hall music and was a major characteristic

of English music through to the 16th century. Descant also emphasises

the intervalof the third, hitherto regarded as a dissonance, and it is

the integration of this interval into a particularly consonant style of

music that distinguishes the «contenance angloise» sound,

and both these aspects of descant later dominate the style of the 15th

century carols.

The 14th century music

In «Thomas gemma / Thomas cesus» the upper pair of voices

has two closely related texts, one in praise of St Thomas of

Canterbury, the other of St Thomas de la Hale of Dover Priory. The

composer handles these brilliantly so that the voice exchange is both

an interweaving and an opposition of the texts and music. The lower

untexted voices also form a pair, partly imitating the upper voices,

but also providing an harmonic basis and, later, enjoying two passages

of hocket.

«Tu civium primas» has not one, but four texts - in praise

of Simon Peter and the foundation of the Christian Churcb. The upper

voices do imitate each other to a certain extent, but this motet is

more harmonically conceived, often using descant over a bass

«pedal» note.

Descant is also used, but freely, in two moteis that invoke the help

ofthe Virgin Mary, «Mater Christi nobilis» and

«Singularis laudis digna», the latter calling for peace in

the «Hundred Years War» with France.

«Civitas nusquam» celebrates Edward the Confessor, who

ruled Anglo-Saxon England in the mid-11th century. This is a more

traditional motet in its manner of textual declamation by two voices

(each with its own text) built around a plainsong tenor laid out in

slow, regular notes. The plainsong has not been identified but is

presumed lo be from the office of St Edward, King and Confessor. Such a

description, however, does not prepare us for the simple beauty of the

resulting music.

Similarly in «Doleo super te» a mostly syllabic declamation

above a slower, partly isorhythmic tenor produces one of the most

tender expressions of personal desolation to be found anywhere in

medieval music. Certainly a place may be claimed for this short piece

alongside other famous laments on this and related texts by composers

such as Josquin, Tomkins and Schütz.

«Alleluia: Hic est» provides a vehicle for vocal virtuosity

in an elaborated descant style (with the tenor, less usually for this

style, in the lower voice). The chromatic intervals create an air of

mannerist strangeness, uncommon in English music at this time as it

moved towards the music of Old Hall and Dunstable.

The «Ite missa est was the dismissal at the end of Mass; tbe

jubilant setting performed here must have sent the congregation

skipping home!

15th century English music

The eminence of the English «contenance» lasted only a

generation or two. According to the Flemish theorist Tinctoris, writing

around the year 1470, whereas Dunstable had been the fount and origin

of the new music (of Dufay, Binchois and later Ockeghem), the English

now «continue to use one and the same style of composition, which

shows a wretched poverty of invention». In terms of the

developing language in Burgundy, France and the Netherland, he was

correct - but it would be wrong to dismiss tbe carols and, a little

later, the music ofthe Eton Choirbook as inferior products in

themselves. In fact both as music and poetry, the 15th century carol,

togetber with its successor the courtly songs and Passion carols in the

Fayrfax Manuscript (c. 1500), constitutes a very important area in the

history of English song.

Almost all the 15th century carols are anonymous, and while many of

them, perhaps the majority, are associated with the festive period from

Christmas to Epiphany, many other subjects are also treated, by no

means all of them religious. There are carols to celebrate military

victories, carols of love, drinking songs, carols in praise of numerous

saints, and carols on themes of a moralistic rather than religious

nature. The definition of a carol has best been formulated by R. L.

Greene as «a song on any subject, composed of uniform stanzas,

and provided with a burden».

Most of the 15th century carols are for two voices joined by a third,

usually in descant style, in the burden. The prevailing melodic idiom

is that of the 15th century chanson, redirected slightly by thbe

inflections of the Englisb language. The carol is thought to have

originated from the early medieval dance songs with their clear

divisions into verse and chorus; but many other influences are felt in

these works, which are products of sophisticated minds, however mixed

and «popular» the audience tlo which they were directed.

Contemporary with the carols are mature examples of the

«contenance angloise» such as Forest's «Tota pulcra

es», with its suave interlacing of vocal lines and sweet

harmonies based on the interval of the third (and with a characteristic

change of metre - at «et vox turturis»). In the slightly

younger John Plummer's «Anna Mater» (Anna, the mother of

the Virgin Mary), we find an early example of the Votive Antiphon which

became such a favourite with English composers towards the turn of the

century.

During the second half of the 15th century, English music became

increasingly conservative, measured against continental models; but as

it has remained so almost continually ever since, we must conclude that

it is the natural tendency of an island race, and that much fine music

can be written on islands!

Paul Hillier