Symphonia 02196

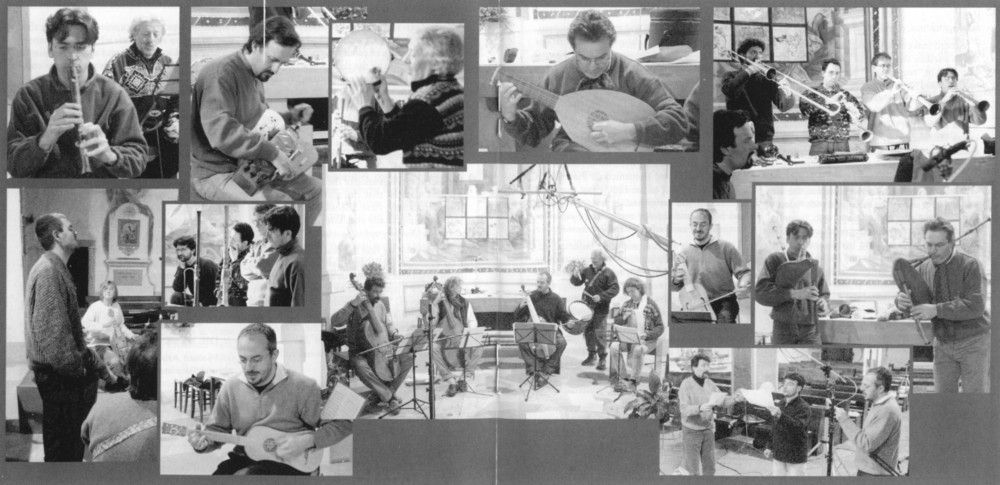

Registrazione: marzo 2002,

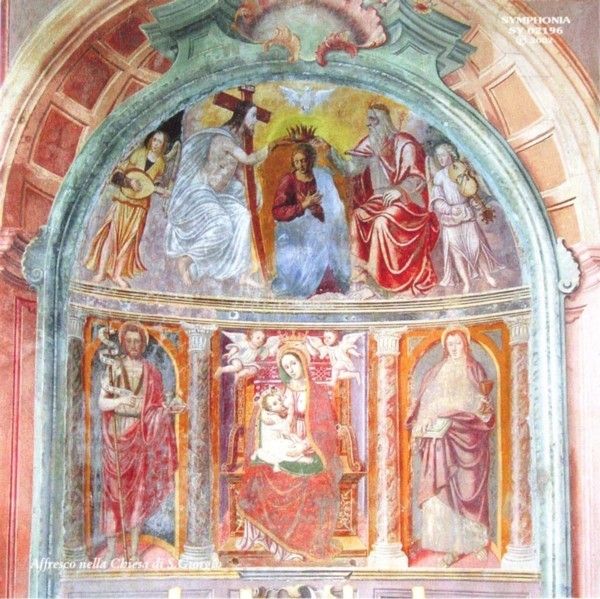

Chiesa di S.Giorgio, Morbio Inferiore, CH

Tecnica : SYMPHONIA, Pugnano, Pisa

Presa del Suono: Roberto Meo

Direttore Artistico: Sigrid Lee

Montaggio Digitale: Sigrid Lee

Produzione: Roberto Meo, Sigrid Lee

Symphonia 02196

Registrazione: marzo 2002,

Chiesa di S.Giorgio, Morbio Inferiore, CH

Tecnica : SYMPHONIA, Pugnano, Pisa

Presa del Suono: Roberto Meo

Direttore Artistico: Sigrid Lee

Montaggio Digitale: Sigrid Lee

Produzione: Roberto Meo, Sigrid Lee

01 - Branle de la “Haye” [2:17]

guitarra MS, cornamusa AS, flauto e tamburino IC, ghironda AC, trombone

FS, bombarde VO AP

02 - Branle des “Lavandieres” [1:44]

liuto AC, viella MS, arpa IC, percussioni UM

03 - Volte [2:51]

viella MS, ghironda AC, liuto AS, flauto IC

04 - Suite. “Hermites”, “Sabots”,

“Chevaulx” [4:45]

viella MS, guitarra MS, ghironda AC, cornamuse AS IC, ciaramello IC,

bombarda AP, trombone FS, percussioni UM

05 - Basse Dance - “Iouyssance vous donneray”

[2:26]

viole MS LA SC SL, percussioni UM

06 - Tourdion - a (Arbeau), b (P Attaignant) [2:01]

ghironda AC, ciaramello IC, bombarde AP VO, trombone FS, percussioni UM

07 - Suite. “Si i’ayme ou mon”,

“I’aymerois mieulx dormir seulette” [1:58]

guitarra MS, liuti AC AS, arpa IC, percussioni UM

08 - Suite. “Charlotte”, “Aridan”

[2:19]

guitarra MS, ghironda AC, cornamusa AS, flauto e tamburino IC

09 - Branle “Cassandre” [2:57]

liuti AS AC, viella SL, voce PE · coro: MS, LA, AM

10 - Branle d’ “Escosse” [2:26]

viella MS, percussioni UM, ciaramello IC, bombarda AP, trombone FS,

cornamusa AS

11 - Branle de la “Torche” [2:01]

guitarra MS, flauto IC, percussioni UM

12 - Allemande [3:02]

cornamuse AS IC, percussioni UM

13 - Pavana - “Belle qui tiens ma vie” [4:23]

viole MS LA SC SL, voce MB, liuto AC, percussioni UM

14 - Suite. “La traditora my fa morire”,

“Anthoinette” [2:08]

viella MS, viole LA SC SL, percussioni UM

15 - Branle de la “Montarde” [2:22]

viella MS, ghironda AC, flauto e tamburino, percussioni UM

16 - Branle de l’ “Official” [1:36]

liuto AS, viella MS, percussioni UM

17 - Branle de “la Guerre” [2:08]

ciaramello IC, bombarda AP, trombone FS, percussioni UM

18 - Suite. Double, Simple, Gay, Bourgogne [2:35]

flauto e tamburino IC, ghironda AC, guitarra MS

19 - Gavotte [1:45]

liuto AC, viella MS, viola LA, flauto IC

20 - Les Bouffons [7:09]

guitarra MS, flauto e tamburino IC, cornamusa AS, ghironda AC,

percussioni UM, bombarda AP, trombone FS

21 - Pavana di Spagna [1:28]

liuti AC AS

Florilegio Ensemble

Marcello Serafini

Isacco Colombo (ic) ciaramelle, flauto e tamburino, arpa, flauti,

cornamusa

Antonio Serafini (as) liuto, cornamusa

Alberto Prugnola (ac) liuto, ghironda

Marcello Serafini (ms) viella, viola, guitarra rinasacientale,

voce

Massimiliano Broglia (mb) voce

Con la partecipazione:

Alta Capella

Alberto Ponchio (ap) bombarda

lsacco Colombo (ic) ciaramello, bombarda

Vincenzo Onida (vo) bombarda

Fedele Stucchi (fs) trombone rinascimentale

Umberto Mosca (um) percussioni

Sabina Colonna Preti (sc) viole

Sigrid Lee (sl) viola, viella

Luigi Annessa (la) viola, voce

Philippe Etienne (pe) voce

Antonio Marchese (am) voce

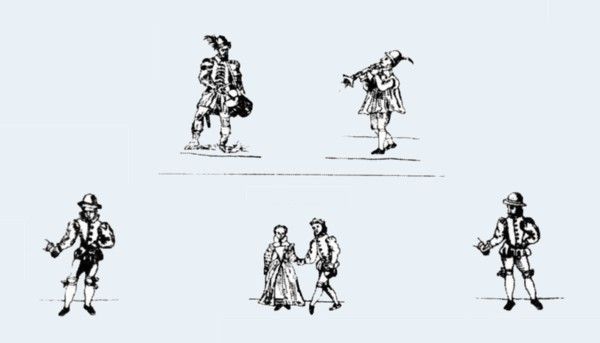

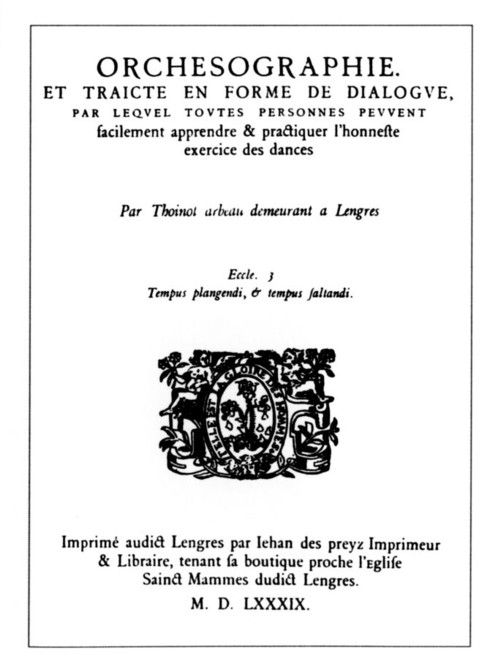

Si un savant chanoine de Langres n’avait eu l’idée

insolite de publier en 1588 un traité sur les danses

pratiquées dans son milieu social et à son époque,

nous ne saurions quasiment rien des danses de la Renaissance

française. La prestigieuse basse dance du XV siècle avait

fait l’objet de quelques écrits sibyllins.

L’Apologie de la danse de F. de Lauze évoque de

façon confuse quelques danses du début du XVIIe

siècle. Mais il faudra attendre Feuillet et Rameau au

début du XVIIIe siècle pour trouver une matière

(relativement) claire et exploitable pour notre connaissance.

C’est dire tout l’intérêt de

l’Orchésographie de Thoinot Arbeau.

Nous y trouvons la description de trente quatre danses communes,

pratiquées tant dans les banquets solennels que dans

d’autres circonstances plus légères. De danses de

ballet point, ou très peu. L’exposé en est clair,

précis et amené par une réflexion

pédagogique pointue. L’un des livres les plus intelligents

jamais écrits sur la danse. Il fait passer également un

ton de conversation et un humour bien propre à ce temps.

L’Orchésographie se situe à une époque

charnière pour l’histoire de la danse. Elle contient

encore des danses héritières des caroles du Moyen Age

(branle de Poictou, Trihory de Bretagne...) aux longues

séquences motrices non analysables en «pas»

constituants. Elle présente également un type de

répertoire que l’on voit émerger à la

Renaissance, jouant sur la combinatoire de pas identifiés

(principalement les simples et doubles), tels les basses dances et le

foisonnement des branles dits «coupés». Mais

l’on voit déjà s’y développer à

travers gaillardes et gavottes l’art qui atteindra son plein

développement dans la belle danse de Louis XIV, celui de la

combinatoire indéfiniment renouvelable de petits mouvements

très brefs à l’intérieur d’un cadre

rythmique strictement défini. En ceci

l’Orchésographie est un outil indispensable à notre

compréhension de l’évolution de la danse.

Le présent enregistrement vient à point. Il est vraiment

conçu pour la danse. Sans chercher à populariser le

répertoire de l’Orchésographie, il en propose une

interprétation qui s’appuie sur la recherche actuelle en

danse de cette époque, avec toute l’exigence des tempi et

des phrasés appropriés. Le qualité de la mise en

place donne aisance et évidence à

l’exécution du danseur.

MÔNE GUILCHER

LA MUSICA

Nell’Orchisographie sono riportate quasi cinquanta

melodie, fra cui solo la Pavana “Belle qui tiens ma vie”

è scritta a quattro parti, con una notazione molto chiara e

facilmente leggibile. Non compare quasi mai la destinazione strumentale

di questi brani, e anche le font storiche, iconografiche o testuali,

non sono chiare sull’impiego degli strumenti per accompagnare la

danza lasciando quindi campo apeno all’esecutore.

Arbeau fa distinzione fra strurnenti utilizzati nella danza

“guerriera” e quelli impiegati nella danza

“ricreativa”. Nella prima stila un elenco di strumenti

“forti” come le buccine, litui, cornetti e tamburi vari,

nella seconda parla di flauto con tamburo, arpe, salteri. Sembra

esserci, quindi, una destinazione degli strumenti intesi come

dinamicamente forti, verso le danze all’aperto e un utilizzo di

strumenti “bassi” per le danze al chiuso; in alcune

testimonianze d’epoca, come nelle incisioni di Jan Theodor de Bry

(1561-1623), vengono rappresentati alcuni strumenti a corde, come la

viola, il liuto, l’arpa, per balli “cortesi” e

ciaramelli e bombarde per danze “contadine”. In altre

iconografie i suonatori di strumenti forti compaiono all’interno

di sale, e suonatori di liuti e arpe in giardini di palazzi. Quindi non

esiste una regola fissa per la scelta degli strumenti, anche se la

formazione strumentale per danze più rappresentata nelle pitture

del tempo è, senza dubbio, quella dei pifferi. Costituita da

ciaramello e bombarda, veniva spesso accompagnata da un trombone per il

registro grave; a questi si aggiungeva, a volte, una seconda bombarda o

un secondo ciaramello. Questa formazione era già presente nel

’400 e perdureri per tutto il periodo rinascimentale. In qualche

caso il ciaramello veniva accompagnato da una cornamusa, come dice lo

stesso Arbeau.

Già ai tempi questa formazione godeva di grande prestigio, ed i

migliori esecutori figuravano fra i più pagati e vezzeggiati a

corte ed impiegati in funzioni civiche e di rappresentanza. In tali

occasioni le cronache ed i trattati che iniziano a compadre nella

seconda meta del secolo in Italia testimoniano sicuramente un ruolo di

primo piano per la danza e la musica per danza intesa come arte cortese

colta e raffinata.

Il fatto che nelle fond pittoriche e letterarie questi musicisti

venissero rappresentati in ensemble fa presupporre un trattamento

polifonico anche delle prime danze monofoniche del ’400,

conservate nei trattati di Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro e di Domenico da

Piacenza. Sara nella prima meta del Cinquecento che usciranno raccolte

a stampa a quattro parti di musica, probabilmente concepite per

ensemble di “piffari” ma anche per viole, flauti o altri

strumenti.

Sulla base di questi ed altri elementi storici, nonché il

suggerimento che la musica stessa o il titolo evoca, abbiamo pensato di

utilizzare, per questa registrazione, diverse formazioni strumentali,

da quelle più raffinate come l’ensemble di viole, a quelle

più popolari come ghironda, cornamusa e chitarra rinascimentale.

Quasi sempre presente l’utilizzo delle percussioni, cosi come

vuole Arbeau. Inoltre abbiamo impiegato anche strumenti più

arcaici, come la viella e il liuto a penna, per sottolineare il

carattere medievale di alcune melodie.

Fra gli strumenti prediletti per i balli vi era sicuramente il flauto e

tamburino: testimoniato da fonti iconografiche già in epoca

tardomedievale, esso assume importanza come strumento per accompagnare

la danza proprio con il codificarsi della stessa come arte misurata e

cortese nel corso del XV secolo. Con il flauto e tamburino un solo

esecutore forniva gil aspetti necessari per accompagnare il bailo -

ritmo e melodia —, un risparmio economico evidente per il nobile

o il signore che doveva pagare i musicisti! Il flauto e tamburino

rimarrà diffuso per tutto il Rinascimento prima di uscire dalla

scena della musica colta, rimanendo tuttavia vivo ancora fino ai nostri

giorni nella tradizione popolare di alcune aree francesi (Béarn,

Provenza) ed europee. Anche nelle esecuzioni e negli arrangiamenti

abbiamo voluto tenere in considerazione i vari ambienti in cui la

musica per danza veniva eseguita, da quelli popolari a quelli

aristocratici.

Nel caso del branle “Cassandre” abbiamo utilizzato un testo

coevo ed eseguito in forma di “canto a bailo” ricalcando

una pratica rinascimentale ancora oggi usata nella tradizione francese

e non solo.

Il disco è stato pensato contemporaneamente ad uso didattico per

i maestri di danza e, come esempio di musica strumentale

rinascimentale, per gli appassionati di musica antica. Ogni brano ha

quindi una introduzione di poche battute per permettere ai ballerini di

prepararsi al bailo e nulla è stato aggiunto o tolto allo schema

descrittivo illustrato da Arbeau.

L’armonizzazione ha seguito criteri di composizione riconducibili

agli esempi desunti dalle “Danceries” di Attaignant,

Gervaise, Susato e altri autori coevi, con uno sguardo anche alla

polifonia più antica e ad una modalità più arcaica.

Al trattamento prevalentemente accordale del tessuto polifonico, non

scevro comunque da “artifizi” contrappuntistici, come

l’imitazione, si sono voluti aggiungere anche elementi

“rapsodici”, “bassi ostinati” o ancora “a

bordone” e un trattamento in alcuni casi più libero della

dissonanza.

La scelta di non utilizzare trascrizioni dell’epoca, tranne nel

caso del Tourdion e del “Branle de la Torche”, è

nata dall’esigenza di fare un lavoro discografico sulle musiche

originali di Arbeau, coinvolgendo l’esperienza e la pratica dei

singoli musicisti e danzatori in un lavoro d’insieme, finalizzato

a rendere più attuale un testo così importante come

l’Orchésographie.

FLORILEGIO ensemble

If a certain scholarly canon of Langres had not had the unusual idea of

publishing, in 1588, a treatise on the dances practiced in his social

environment and epoch, we would know next to nothing about the dances

of the French Renaissance. The prestigious basse danse of the

15th century had been the subject of some sibylline writings. The L'Apologie

de la danse by F. of Lauze evokes in a confused way some dances

from the beginning of the 17th century. But it not until the writings

of Feuillet and Rameau at the beginning of the 18th century that we

find material that can give us information that is (relatively) clear

and usable. This tells us just how important and interesting Thoinot

Arbeau's Orchésographie is to us.

In his book we find the description of thirty-four common (ballroom)

dances, practiced as often in solemn banquets as in other lighter

circumstances. There is little or nothing about theatrical dances. The

exposition is detailed and practical with a decidedly educational bent

and the treatise can be considered one of the most intelligent books

ever written on dance. At the same time the tone is conversational and

full of the humor of those times.

Orchésographie dates from an epoch that was a turning point in

the history of dance. It contains many archaic dances that are direct

descendants of medieval carols (branles de Poictou, Trihory de

Brittany ...) with long sequences that cannot be analysed in terms

of constituent “steps”. It also presents a type of

repertoire that was emerging at the time of the Renaissance, such as

the basses danses and the abundance of branles called “coupés”

which play on the combining of identified steps, (mainly the simple and

the double). But we can already see in the galliards and gavottes what

will reach its full development in the court dance of Louis XIV,

consisting in indefinitely extendable combinations of very brief and

small movements inside a strictly defined rhythmic setting.

Orchésographie is an indispensable aid in understanding the

evolution of dance.

The present registration has been specifically conceived for dancing.

Without trying to popularise the repertoire of Orchésographie,

it offers an interpretation that takes into consideration the present

research on the dance of this time, and the requirements in terms of

tempo and phrasing. The settings are intended to offer ease clarity and

to the dancer's performance.

MÔNE GUILCHER

Translation: Sigrid Lee

THE MUSIC

Thoinot Arbeau's Orchésographie contains almost fifty

melodies. Only one, the pavane “Belle qui tiens ma vie” is

written in four-part harmony, in very clear, legible notation. There is

almost no mention of the instruments to be used in playing these

melodies, and historical, iconographical and literary sources are not

clear on what instruments should accompany the dances, leaving the

field, therefore, open to the performer.

Arbeau makes the distinction between instruments used in the

“warlike” dances and those employed in

“recreational” dances. For the first, he lists

“loud” instruments such as bugles, lutes, cornetts and

various drums. For the second he speaks of pipe and tabor, harps and

psalteries. It would seem from this that the loud, dynamically strong

instruments are to be used for the dances outside in open air, and the

soft ones for the dances indoors. In other documents of the epoch, such

as the engravings of Jan Theodor de Bry (1561-1623), string instruments

such as the viol, lute and harp seem to be associated with

“courtly” dances — shawms and cornetts with

“country” dances. In still other iconographical sources,

however, performers of loud instruments appear indoors whereas

lutenists and harpists are seen outside in the palace gardens. So there

is no fixed rule governing the choice of instrumentation, but it is

true that the instrumental combination most often represented in

paintings of the time where dancing is portrayed, is without a doubt,

the piffari, or wind band consisting of shawms of various

sizes, often with a sackbut to cover the lower register. This basic

combination was already present in the 15th century and persisted for

the entire Renaissance period. In some cases the shawm was accompanied

by a bagpipe, as Arbeau himself mentions.

This combination of instruments enjoyed great prestige at that time,

and the best players were the most highly paid and doted upon of the

court and were employed in civic and theatrical functions. On such

occasions the chronicles and treatises that begin to appear in the

second half of the century in Italy testify to their primary role in

dance accompaniment and dance music itself as a culturally refined

courtly art.

The fact that in the pictorial and literary sources these musicians

were represented in groups would imply a polyphonic treatment of some

of the first dance tunes of the 15th century, transcribed in the dance

treatises of Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro and Domenico da Piacenza. It was

in the first half of the 1500's that music for four voices was

published in print. They may have been conceived for ensembles of piffari

or for viols, flutes and other instruments as well.

On the basis of these and other historical elements, together with the

ideas the music or titles themselves evoke, different instrumental

combinations have been used on this recording, from those more refined

such as an ensemble of viols, to those more popular such as the

hurdy-gurdy, bagpipe and Renaissance guitar. Percussion instruments

have been used almost overall, as Arbeau himself instructs. In some

cases more archaic instruments such as the fiddle and plucked lute have

been used, to suit the medieval character of certain melodies.

One of the favorite instruments for dance was certainly the pipe and

tabor: iconographical sources of the late middle ages testify to its

importance as an accompanying instrument to the dance and went on to be

codified as a measured and courtly art during the course of the 15th

century. With the pipe and tabor one single performer could furnish the

necessary elements essential to accompanying dance - rhythm and melody

-. This was an obvious way of economising for the nobleman or gentleman

who had to pay the musicians! The pipe and tabor would remain

widespread for the entire Renaissance before leaving the scene of

cultural music, remaining nevertheless active still today in the

popular tradition of Béarn and Provence in France and in some

other European areas.

In our arrangements and performances of the dances of Arbeau, the

various environments in which they might have been performed have been

taken into consideration, from the more popular to the more

aristocratic.

In the case of the branle “Cassandre” a text contemporary

to the music has been set and performed in the form of a “dance

song”, a Renaissance practice used still today in France and in

other traditions.

In addition to its value as a collection of music to be enjoyed, this

recording was conceived partly with the aim being an important tool in

the teaching of Renaissance dance. Every piece, therefore, has an

introduction of a few bars to allow the dancer to prepare and the

original forms have been respected: nothing has been added or removed

from the descriptive scheme illustrated by Arbeau.

The tunes have been harmonized according to compositional criteria

based on examples in the “Danceries” of Attaignant,

Gervaise, Susato and other composers of the time, with regard also to

earlier polyphony and more archaic modality.

Together with a fundamentally chordal treatment, some contrapuntal

devices such as imitation have been included along with some

“rhapsodic” elements, ostinato basses, drones and

some free use of dissonance.

The choice not to use already existing transcriptions from the epoch,

(except in the case of the Tourdion and the Branle de the

Torche), came from the desire to be in direct contact with Arbeau's

words and music, dancers and musicians together, with a fresh and

uncluttered outlook on such an important work as Orchesographie.

FLORILEGIO ensemble

Translation: Sigrid Lee

«Uno de los libros de música más curiosos editados

en el Renacimiento es la Orchésographie de Thoinot Arbeau

(Langres, 1589), un clérigo natural de Dijon que, tras realizar

estudios de derecho, ocupó diversos cargos en la catedral de

Langres. Se trata de un manual de danza, el único publicado en

Francia en la segunda mitad del siglo XVI, que fue reeditado en 1596

bajo el título de Métode et teorie en forme de

discours et tablature pour apprendre a dancer, battre le tambour en

toute sorte & diversité de batteries [...] fort convenable

à la jeunesse. Arbeau, experto danzarín en su

juventud, pensaba que el baile era una forma de imitar la

armonía o movimiento de las esferas y, a la vez, uno de los

mejores métodos para encontrar pareja.

Su tratado está escrito en forma de diálogo y describe

con todo lujo de detalles, mediante una ingeniosa tabulatura que se

supone inventada por él, las danzas que estaban de moda en su

tiempo e incluso antes. Figuran entre ellas la baja danza y el

tordión, la pavana y una variedad suya, la pavane

d’Espagne, hasta quince variantes de la gallarda, diversos tipos

de branle, la courante, la allemande, la morisca y otras varias danzas.

El Florilegio Ensemble ofrece aquí una selección de 21 de

las danzas sonoramente recuperables del tratado de Arbeau, siguiendo

sus instrucciones instrumentales. Más que un trabajo

filológico se trata de un trabajo de adaptación, puesto

que, en lugar de servirse de las transcripciones disponibles de la

época, se basa en los fragmentos de música que aparecen

en el tratado, a los que dan vida valiéndose de su propia

experiencia como intérpretes. El resultado,

interesantísimo, resulta de una gran frescura y muy vivo, lo que

convierte a este CD en una delicia para el oyente.»

Maricarmen Gómez, Goldberg, agosto 2003