medieval.org

Studio SM D2819

1999

medieval.org

Studio SM D2819

1999

1. Introit. Puer natus est (chant. BNL lat 17311) [4:35]

ténors OG* RB AG, baryton JPR, baryton-basse EV*, basse PhR

2. Kyrie. Jhesu Deus dulcissime à 4 (Apt 16 bis) | De Fronciaco [5:17]

3. Gloria à 4 (Bologne Bu 2216) | Bosquet [2:32]

ténors AG RB, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR

4. Collecte. Concede, quesumus (chant. BNL lat 17311) [1:15]

baryton JPR, baryton-basse EV

5. Graduel. Viderunt omnes (chant. BNL lat 17311) [4:02]

ténors OG RB* AG, baryton JPR*, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR

6. Alleluia. Dies sanctificatus à 2 (Florence Plut 29,1) [6:54]

ténors OG RB AG, baryton JPR, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR

7. Sequence. Letabundus (chant. BNL lat 17311) [2:27]

ténor AG*, baryton JPR*, baryton-basse EV*, ténor OG*, ténor RB*, basse PhR*

8. Credo à 4 (Apt 16 bis) | Bonbarde [6:49]

OG RB, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR

9. Offertoire. Tui sunt celi (chant. BNL lat 17311) [4:38]

ténor AG, baryton JPR*

10. Preface (chant. BNL lat 17311) [2:11]

baryton JPR

11. Sanctus 'Saint Omer' à 3 (Padoue Bu 1475) [3:19]

ténors OG RB* AG, baryton JPR*, baryton-basse EV*, basse PhR

12. Agnus Dei à 3 (BM Cambrai 1328) [4:04]

ténors OG* RB AG, baryton JPR*, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR*

13. Communion. Viderunt omnes (chant. BNL lat 17311) [3:04]

ténors OG RB AG*, baryton JPR, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR*

14. Post Communion. Presta, quesumus (chant. BNL lat 17311) [1:12]

baryton JPR, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR

15. Post Missarum. Ite missa est à 4 (Ivrée BC 115) [3:14]

ténors OG RB, baryton-basse EV, basse PhR

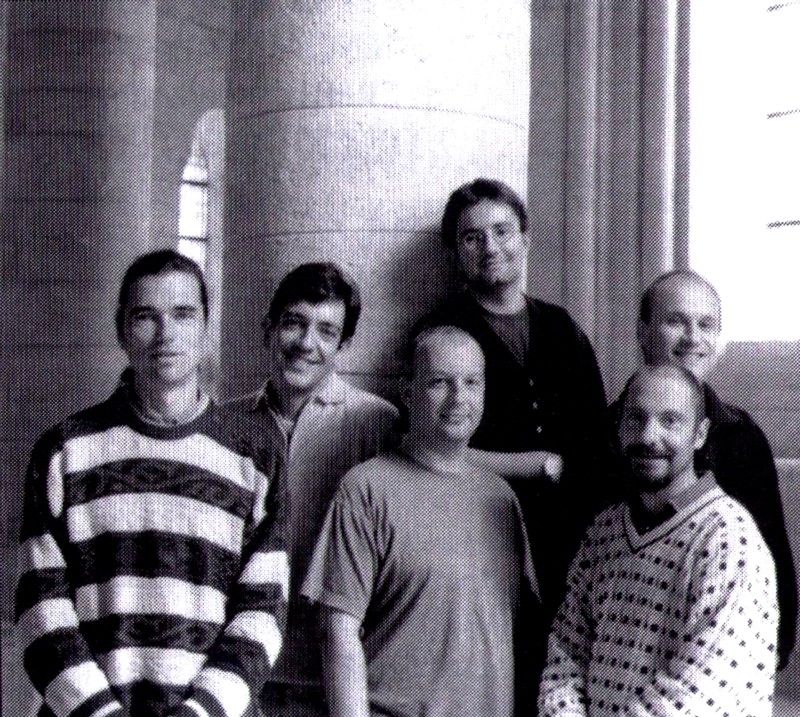

ENSEMBLE

DIABOLUS IN MUSICA

Antoine Guerber

Raphaël Boulay, ténor - RB

Olivier Germond, ténor - OG

Antoine Guerber, ténor - AG

Jean-Paul Rigaud, baryton - JPR

Emmanuel Vistorky, baryton-basse - EV

Philippe Roche, basse - PhP

(* = soliste)

Ensemble missionné par le Conseil Régional du Centre

Enregistrement du 22 au 25 septembre 1999 en l'Abbaye de Fontevraud

Direction artistique, prise de son, montage : Jean-Marc LAISNE

Enregistreur Nagra 24 bits digital - Micros : Bruel et Kjaer 4003 - Montage : Station Pyramix

Tous les manuscrits datent du XlVe siècle ou du tout

début du 3CVe siècle. L'ordinaire polyphonique est

chanté d'après l'édition de G. Canin et F. Facchin

(Polyphonic music of the 14th century). Le propre grégorien est

chanté directement d'après le manuscrit. Remerciements

chaleureux à M. Bruno ROY (université de Montréal)

pour ses précieuses traductions et ses encouragements constants,

ainsi qu'à Mme Isabelle RAGNARD pour ses conseils judicieux au

début de notre travail.

Illustration de couverture :

Avignon - Bibliothèque Municipale

MS 136 - Folio 152 - Missel du XIVème siècle

Cliché : CNRS/IRHT

Ⓟ 1999 Studio SM

Missa Magna

MESSE À LA CHAPELLE PAPALE D'AVIGNON

(XIVE SIECLE)

Le voyageur qui arrive en Avignon par l'ouest, en venant de

Villeneuve-lès-Avignon et en franchissant le Rhône, est frappé de nos

jours comme probablement au Moyen Age, par l'un des plus beaux paysages

urbains de France : la masse imposante du Palais des Papes domine la

ville ancienne ramassée au pied du rocher des Doms et enserrée dans les

remparts crénelés construits par Urbain V. Ce voyageur ne peut manquer

de s'interroger sur les raisons de l'existence dans cette ville moyenne

du plus imposant palais médiéval de notre patrimoine.

Pendant un peu moins d'un siècle, le monde chrétien eut les yeux

tournés vers Avignon, car des papes français y résidèrent à partir de

1309. Ses richesses, ses fastes, ses lieux de pouvoir y ont attiré les

rois, les princes et les plus grands artistes du siècle. Peuplée de 5 à

6 000 habitants à l'arrivée de Clément V, Avignon va devenir en

quelques années la seconde ville de France derrière Paris. On parle de

100 000 Etrangers dans la ville papale au milieu du siècle... On

comprend alors aisément la frénésie de construction qui s'empara de la

cité, qui ne vint pourtant jamais à bout de la pénurie de logements

nécessaires : maisons bourgeoises, Eglises, couvents, livrées

cardinalices et bien sur Palais des Papes, bouleversèrent la

physionomie d'Avignon et de ses environs immédiats. On comprend

également les anathèmes lancés par Pétrarque, qui fustige la “captivité

de Babylone”, contre les excès de la vie dans la cité rhodanienne.

Ce sont des circonstances uniquement politiques qui amenèrent Clément

V (Bertrand de Got) à venir s'installer, provisoirement pensait-il, en

Avignon, continuant ainsi la tradition de la papauté itinérante des

XIIe et XIIIe siècles (plusieurs papes du XIIIe siècle ne vinrent

jamais à Rome!). “Ubi papa, ibi Roma”: là où se trouve le pape, là est

le siège de la chrétienté. Philippe le Bel, qui avait favorisé

l'élection de ce pape d'origine gasconne et qui garda toujours une

forte influence sur lui, l'avait poussé à s'installer dans une région

où il pouvait exercer son autorité beaucoup plus facilement qu'en

Italie, instable et secouée de nombreuses crises politiques. L'Eglise

sera durant tout ce siècle un lieu de lutte de pouvoir entre les

différents souverains d'Europe et révélera l'importance puis le déclin

de la prédominance française. Ce sont les mêmes troubles au sein des

Etats Pontificaux qui retardèrent le retour du souverain pontife en

1376 dans la ville dont il était également l'évêque: Rome.

Tant que l'influence des rois de France successifs sut se faire très

prégnante au sein du collège des cardinaux, c'est à dire presque tout

au long du XIVe siècle, des papes français furent élus à la fonction

suprême. Des personnalités très contrastées se succédèrent sur le

Saint-Siège. De l'autoritaire jean XXII (le cahourcin Jacques Duèse) à

l'obstiné Benoît XIII (l'aragonais Pedro de Luna) qui refusa d'abdiquer

jusqu'à sa mort en exil à 95 ans, alors que les grands rois du monde

chrétien s'étaient résolus depuis longtemps à mettre enfin un terme au

Grand Schisme. L'austère cistercien Benoît XII par exemple (le gascon

Jacques Fournier), grand pourfendeur du catharisme1, se vit succédé par

le brillant, le fastueux Clement VI dit le “Magnifique” (le limousin

Pierre Roger) qui transforma la Curie et le palais de son prédécesseur

en l'une des plus éclatantes cours d'Europe, faisant d'Avignon la

capitale des Arts et des Lettres. Les points communs entre ces

différents papes français furent d'une part des liens très forts avec

les rois de France, liens diplomatiques et politiques qui souvent

n'exclurent pas une certaine amitié, et d'autre part un “népotisme

absolu”, qui voyait chaque souverain pontife, à l'exception notable de

Benoît XII, nommer systématiquement des membres de sa famille aux

charges de cardinaux ou d'officiers importants de la curie.

Ces personnages hauts en couleur traversèrent un siècle

particulièrement riche d'évolutions fondamentales, de bouleversements

et d'événements dramatiques, qui se termina dans la confusion du Grand

Schisme. La grande peste noire de 1348, en provenance de Marseille, est

largement connue. En Avignon, elle n'était, hélas, que la première

d'une longue série (1348, 1361, 1397, 1406). La France compte 20

millions d'habitants en 1328, comme à la fin du XVIIe siècle, mais 10

millions seulement en 1450! Des guerres incessantes et meurtrières

s'ajoutèrent en effet au fléau de la peste. A la fin du XIVe siècle, la

noblesse, désargentée par ces guerres ruineuses, ne joue plus vraiment

son rôle traditionnellement protecteur de la population et semble même

se réfugier dans une sorte de fuite en avant dans le luxe et les

plaisirs. La musique du XIVe siècle est bien entendu le reflet de ce

monde et de ces temps si troublés, de cette société qui se sécularise.

Les fondements mêmes de la pensée médiévale, qui décrit le monde comme

miroir de l'harmonie universelle, sont bousculés par une véritable

révolution scientifique qui commence à raisonner sans le secours de la

foi. Et c'est bien sûr au cours de ce siècle que l'expression

individuelle de l'artiste se personnalise fortement en cherchant à

s'affranchir des canons traditionnels.

Notre programme est

très intimement lié à un bâtiment prestigieux et relativement bien

conservé: le Palais des Papes, construit principalement par Benoît XII

et Clément VI, et notamment la chapelle St Pierre (chapelle

“Clémentine”) dans laquelle se concentrèrent toutes les liturgies

solennelles. De nombreux autres lieux de culte existaient dans le

palais qui comportait six chapelles et beaucoup de grandes salles

susceptibles de recevoir des autels portatifs. Il faut se représenter

les lieux immenses et vides que nous pouvons visiter aujourd'hui comme

ils pouvaient l'être du temps de leur splendeur. Le mobilier y était

luxueux; les jours de fête, les murs étaient largement recouverts de

tentures et de tapisseries richement décorées, laissant entrevoir le

somptueux décor pictural que nous pouvons encore admirer aujourd'hui

par endroits2. En certaines grandes occasions, la foule suivait les

nombreuses processions et était autorisée à assister aux liturgies. On

se pressait alors pour mieux voir les vêtements chamarrés des

cardinaux, les brillantes décorations ornant l'autel et le choeur, la

magnifique cathèdre du pape derrière l'autel, et pour écouter les

extraordinaires et nouvelles compositions polyphoniques des chantres,

logés dans leur enclos particulier à l'est de la chapelle St Pierre.

Dès les années 1330, l'Eglise collecte très efficacement ses revenus,

ce qui n'était pas le cas à la période précédente, et les coffres du

trésor se remplissent rapidement. Il est difficile d'imaginer le luxe

très peu évangélique de la Curie avignonnaise. S'il peut nous paraître

choquant aujourd'hui, il nous faut reconnaître que le Palais des Papes

devint rapidement un centre artistique fondamental, idéalement placé à

mi-chemin de Rome et de Paris, pour lequel travaillèrent, et dans

lequel vécurent les plus grands artistes de ce temps: musiciens,

peintres, poètes, sculpteurs, architectes... Les artistes du nord de

l'Europe y apprirent l'art de la fresque et de la miniature italiennes,

tandis que les artistes italiens s'y familiarisèrent avec la sculpture

et l'architecture de l'Europe du nord. Au début du règne de Clément VI,

par exemple, cinq hommes parmi les plus brillantes figures du siècle,

1e, le musicien Philippe de Vitry, le peintre Matteo Giovannetti, le

poète Pétrarque, l'astronome Johannes de Muris et le mathématicien Levi

ben Gerson, eurent sans doute de très riches discussions ensemble!

Au sein de la Curie, “la chapelle papale” est une institution créée

par Benoît XII en 1334 pour remplacer la “Schola cantorum” romaine, qui

ne suivait pas le pape dans ses nombreux déplacements. Elle comprend

dès le départ 12 chapelains, nombre qui variera peu, à ne pas confondre

avec les chapelains “commensaux”, dignitaires de haut rang partageant

le repas du pape, souvent conseillers ou hauts fonctionnaires de la

Curie. Cet ensemble de chantres va acquérir une renommée considérable

au cours du XIVe siècle et cette lumière attirera plus tard Dufay,

Agricola, Josquin.... Si les peintres choisis pour la décoration du

palais furent principalement italiens, les clercs appelés à participer

à la chapelle venaient pour la très grande majorité d'entre eux du nord

de la France. Clément VI, notamment, reprend une pratique déjà établie

et institutionnalise une tradition qui durera plus de deux siècles,

expliquant ainsi la forte influence française désormais exercée sur la

liturgie papale, jusque là très romaine. Ces chapelains étaient les

meilleurs chanteurs du monde occidental. Le pape n'hésitait pas à les

recruter dans les chapitres des grandes cathédrales ou dans les

chapelles privées des cardinaux et des rois. Engagés pour chanter les

messes et les heures canoniales, ils étaient également souvent

compositeurs de musique sacrée tant que profane et devaient très

probablement participer aux divertissements de fin de repas du pontife

et de ses invités de marque en chantant leurs motets. Au nom du respect

très strict de la règle interdisant à la Curie tout mélange des

domaines sacré et profane, le pape ne pouvait avoir à son service

particulier des ménestrels, mais ses chapelains et les musiciens de ses

hôtes comblaient ce manque. Le “pape gay qui jolyement et doucement

escouteras sans desplaysance” décrit dans un virelai du manuscrit de

Chantilly, est probablement Clément VII (Robert de Genève), amateur de

festivités extraordinaires, dont on sait d'ailleurs qu'il chantait

remarquablement. Son pontificat à la fin du siècle représente le summum

du faste avignonnais. Les archives vaticanes ont été heureusement

préservées et il est émouvant pour nous de connaître très exactement le

nom de tous les chapelains et de leurs “magister” qui se sont succédés

au Palais des Papes. Les comptes très précis nous indiquent également

le haut degré de richesse que leur fonction leur permit d'atteindre en

fin de siècle. Les “cantores” du XIVe siècle donnent l'impression d'une

caste très fermée, d'une confrérie solidaire d'un très haut niveau

artistique et intellectuel, et qui en a d'ailleurs fortement

conscience. Les contacts entre chapelains des différentes chapelles

étaient nombreux et les répertoires semblent avoir beaucoup plus

circulé qu'on ne l'a d'abord cru.

Cette remarque est particulièrement valable pour le genre principal

qui nous préoccupe ici: la messe polyphonique. L'habitude de chanter

l'ordinaire de la messe en polyphonie va considérablement se développer

dans la seconde moitié du siècle, à l'initiative de la chapelle papale.

Le répertoire de l'Ecole de Notre Dame, au XIIIe siècle, comportait

déjà quelques textes courts (Kyrie, Sanctus et Agnus) mis en

polyphonie, mais les compositeurs du XIVe siècle généralisent cette

pratique et s'intéressent surtout aux Gloria et Credo dont les textes

plus longs leur permettent d'innover davantage. A la fin du siècle, la

messe polyphonique est devenue un genre très important qui va

rapidement se répandre à partir de son centre quasi unique de création:

la chapelle papale. Les manuscrits qui nous transmettent ces musiques

de messe viennent presque tous, indirectement, de la chapelle, même si

beaucoup de pièces copiées et transmises en Avignon ont en fait

peut-être été créées ailleurs. L'habitude était alors de choisir, pour

un jour donné, les différents morceaux de l'ordinaire qu'il convenait

de chanter, sans véritables relations musicales entre eux, mais le

souci de donner une unité qui n'est plus seulement textuelle se fait

jour peu à peu. Les messes de Tournai, de Machaut, de Toulouse et de

Barcelone, sont toutefois des exceptions précoces, et la messe sur

cantus firmus unique n'apparaîtra qu'au XVe siècle, avec Guillaume

Dufay. La polyphonie improvisée a toujours coexisté avec ces nouvelles

compositions très savantes, et en dehors d'Avignon, des grandes

cathédrales et des chapelles privées des grands princes, la polyphonie

devait surtout être improvisée. Jean XXII, en 1324-1325, s'éleva bien

contre les abus des jeunes compositeurs de la nouvelle école (Ars

Nova), qui introduisaient hoquets et notes brèves dans leurs chants, et

surtout, comme ses deux prédécesseurs, contre les risques de

laïcisation du chant sacré, mais la situation changea radicalement en

1342 quand Clément VI commença à recruter systématiquement les

meilleurs chantres du nord de la France. A partir de cette date

précise, l'ordinaire polyphonique est attesté à la chapelle papale,

mais il devait y être présent lors des grandes fêtes depuis longtemps

déjà. A la fin du siècle, la polyphonie était autorisée à la messe pour

tout le temps liturgique excepté le temps de la Passion, soit 50

semaines environ, et ceci même en l'absence du pape ! Il n'existe par

contre aucune musique polyphonique pour les heures canoniales. Les

chantres devaient certainement improviser polyphoniquement sur le

plainchant.

La règle toujours respectée à la chapelle

papale était le chant soliste a cappella, bien que les effectifs aient

permis de doubler les voix, et que cette possibilité fut sans doute

parfois exploitée. La première mention d'un orgue concerne la chapelle

de l'anti-pape en exil Benoît XIII, au début du XVe siècle. De même,

les voix de garçons qui commencent à être utilisées dans les chapelles

des cardinaux, sont strictement prohibées au service du souverain

pontife. Trois types de messes pouvaient être célébrées au palais: la

“missa secreta”, ou “privata”, quotidienne, non publique, dite et non

chantée, qui se déroulait dans une petite chapelle privée (appelée

autrefois “sancta sanctorum” dans le palais du Latran à Rome), la

“missa coram papa” qui ne se définit pas par son degré de solennité

mais par l'absence du pape à la célébration ou par le fait qu'il ne

fait qu'y assister sans y participer activement, et la “missa magna”,

grande messe solennelle et publique, toujours chantée dans la grande

chapelle St Pierre selon le rituel particulier de la liturgie papale.

Il n'existe pas à proprement parler de style “avignonnais”. Les

compositeurs d'ordinaires polyphoniques ont simplement utilisé et

développé les trois principaux styles en vigueur à leur epoque :

• le style conduit:

homophonie sans doute parente de la polyphonie improvisée plusque de

l'Ecole de Notre-Dame, mais qui peut intégrer toutes les nouveautés

audacieuses de l'Ars Nova.

Kyrie: le texte

liturgique très court du Kyrie est ici amplifié par un trope, une

pratique ancienne qui connaît un regain de faveur à la chapelle papale.

La rubrique “De Fronciaco” dans le manuscrit concerne la ville de

Fronsac, près de Bordeaux, sans que nous puissions savoir s'il s'agit

du lieu d'origine du compositeur, de son nom, ou d'une simple manière

de désigner cette pièce. Elle est extraite du célèbre manuscrit d'Apt.

Andrew Tomasello croit avoir récemment identifié le scribe principal et

compilateur du manuscrit: Richard de Bozonville, le dernier maître de

chapelle au Palais des Papes d'Avignon, originaire de St Dié. Nommé

prévôt de la cathédrale d'Apt en 1400, il y emporta avec lui ce

précieux manuscrit comportant le répertoire chanté à la chapelle

pontificale. Antoine GUERBER (tous droits réservés)

Bibliographie

• the conduit

style: homophony, doubtless the ancestor of improvised polyphony rather

than of the School of Notre Dame, but which was capable of assimilating

all the daring new inventions of Ars Nova.

1 see Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie's famous book, Montaillou, village occitan

• le style

• le style cantilène:

sous le “tapis instrumental” que les voix inférieures lui déroulent,

une seule voix a un texte, à l'imitation des rondeaux, virelais,

ballades profanes, mais sans refrain.

Gloria: les deux voix supérieures se

chevauchent et se répondent, comme dans beaucoup de motets. L'auteur

est Bosquet, c'est à dire Johannes de Bosco, clerc de Tournai et

chantre de la chapelle papale en fin de siècle, qui travailla sous la

direction de Richard de Bozonville.

Credo: pièce du

manuscrit d'Apt en style conduit, célèbre pour ses jeux rythmiques

dynamiques tout au long du morceau. La rubrique “Bonbarde” pourrait

faire référence à l'auteur, probablement Perrinet, un fameux joueur de

bombarde (instrument à vent de la famille des chalémies), ménestrel au

service du roi d'Aragon.

Sanctus: pièce en style conduit

très homophonique, qui paraît bien archaïque dans ce manuscrit italien

tardif, n'étant pas sans rappeler la première messe cyclique complète

de notre histoire musicale: la messe de Tournai. La rubrique du

manuscrit mentionne d'ailleurs la ville voisine de Saint Omer, très

actif centre urbain du XIVe siècle.

Agnus: également en

style conduit, cette pièce comporte d'impressionnantes marches

harmoniques montantes puis descendantes dans chacune des trois parties

de l'Agnus, qui présentent un début semblable et une fin différente.

Ite missa est:

double motet isorythmique tiré du manuscrit d'Ivrée. Venant directement

de la chapelle papale, ce manuscrit fut probablement écrit pour, ou en

l'honneur de Gaston Fébus, comte de Foix, Seigneur de Béarn, grand

amateur et connaisseur de musique. Les deux textes constituent ce qu'on

appelait au Moyen Age une “revue des états”, c'est à dire des

prescriptions et des principes moraux destinés à toutes les classes de

la société. Il s'agit d'un genre bien attesté en latin, mais également

en français: l'usage qu'on en faisait à la messe, en langue vulgaire,

se dénommait alors “les prières du prône”.

La messe choisie

est celle du jour de Noël, qui devait donc être célébrée dans la grande

chapelle St Pierre, que le pape soit présent ou non.

L'introït, la communion et les deux petites lectures (collecte et post-communion) sont “chantées à la quinte”, improvisées en “chant sur le livre” (cantus super librum).

Il s'agit d'une pratique d'embellissement de la monodie grégorienne,

très vivante et très courante jusqu'au XVe siècle, pourtant

complètement négligée par les interprètes d'aujourd'hui. Dans

d'innombrables lieux de culte simples et n'ayant pas le prestige ni les

moyens des cathédrales et des chapelles privées des princes, il

s'agissait même de la seule forme de polyphonie qui eût été pratiquée

durant tout le Moyen Age. Le chantre Elias Salomon, en 1274, nous parle

déjà de cette pratique d'improvisation sur le livre en mouvements

parallèles et non contraires, et de la manière très “concertante” dont

les chanteurs peuvent concrètement l'appliquer sous la direction d'un

“magister” qui chante également. Plus tard, quatre traités nous

décrivent explicitement cette procédure ornementale simple et

naturelle, tellement évidente qu'elle n'est, à la limite, même pas

considérée comme de la polyphonie, et basée sur une tradition orale

très ancienne, peut-être spécifique aux pays de langue d'oïl. Les

unissons et les croisements de voix y sont des exceptions,

contrairement au déchant, beaucoup plus savant. Il ne s'agit aucunement

d'une pratique “folk”, mais d'une technique de base enseignée aux

jeunes clercs, et destinée uniquement au chant sacré.

Le procédé utilisé pour le graduel,

le rajout d'un faux-bourdon, est historiquement plus sujet à caution,

bien que tous les interprètes du XXe siècle l'utilisent largement. Très

séduisant à l'oreille, il rappelle l'organum de l'Ecole de Notre Dame.

L'offertoire est chanté en simple monodie.

Il est

difficile pour les chanteurs que nous sommes de déterminer avec

précision un type d'interprétation de la monodie grégorienne de la fin

du Moyen Age. Malgré une certaine continuité, la pratique du

plain-chant a varié au cours des siècles. Rythmiquement, le chant a

tendance à s'égaliser peut-être dès la fin du XIIe siècle, sous

l'influence de la réforme cistercienne. Mais quel “tempo” choisir? Si

le rythme de la musique mesurée ralentit sensiblement aux XIII et Xlve

siècles, Stephen Van Dijk pense qu'au contraire l'interprétation du

plain-chant est un peu plus rapide à la fin du Moyen Age, sous

l'influence des frères prêcheurs qui veulent consacrer plus de temps

aux études et aux prédications, et moins aux offices divins. Et l'on

connaît l'influence qu'ont exercée les réformes des frères prêcheurs

sur les habitudes liturgiques de la Curie papale. La liturgie romaine,

déjà très largement simplifiée par Innocent III au XIIIe siècle, est

encore raccourcie en Avignon. Les textes de prières se spécifient, les

chapelains suppriment les longues pauses dans l'exécution des psaumes.

La chapelle papale semble avoir sensiblement abrégé tous les offices,

même ceux des jours de fête. Si certaines cérémonies sont interminables

(neuf heures pour le couronnement de Grégoire XI !), cela est dû au

rituel et au cérémonial particuliers, notamment les fameuses

processions, mais pas aux chants ni aux prières. Mais l'on sait par

contre que le plain-chant est toujours chanté un peu plus lentement les

jours de grandes fêtes... En ce qui concerne l'Alleluia du jour

de Noël, nous interprétons la version du Magnus Liber de l'Ecole de

Notre Dame. Ceci pourrait sembler anachronique dans une messe de la fin

du XNe siècle, mais il faut savoir d'une part, que les organa de ce

répertoire ont été chantés tout au long de ce siècle, notamment bien

sûr à la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, et d'autre part que

l'inventaire des livres de la bibliothèque papale effectué en 1339 pour

Benoît XII en Avignon, décrit deux livres, manifestement destinés à des

chanteurs, contenant le répertoire de Notre-Dame de Paris. De plus, la

description de l'un de ces deux livres nous fait beaucoup penser au

fameux manuscrit de Florence, le plus bel exemplaire des manuscrits

nous ayant transmis ce répertoire et dont est tirée la version de

l'alleluia que nous avons choisie. Enfin, François de Conzié, le

dernier Grand Chambrier du Palais des Papes d'Avignon (véritable “bras

droit” du pape) nous explique en 1409 que l'organum peut encore être

chanté à la messe en circonstance de faste!

1 Cf. le célèbre livre d'E. Le Roy Ladurie : Montaillou, village occitan.

2 Les récents travaux B. Vingtain ont montré avec surprise que ce décor n'était

pas sulement dû au fastueux Clément VI, mais également au prétendu “austère” Benoît XII...

H. ANGLES : La música sagrada de la capilla pontificia de Avignon en la capilla real aragonesa durante el s. XIV.

H. BESSELER : The manuscript Bologna BU 2216.

N. BRIDGMAN : La musique dans la société française au temps de l'Ars Nova.

G. GATTIN et F. FACCHIN : Polyphonic music of the 14th c.

G. CHEW : The early cyclic mass as an expression of royal and papal supremacy.

S. CLERCX-LEJEUNE : Les débuts de la messe unitaire et de la missa parodia au XIVe s.

J. DYER: A 13th c. choirmaster : the “scientia artis musicae” of Elias Salomon.

D. FALLOWS : L'origine du manuscrit 1328 de Cambrai.

S. FULLER : Discant and the theory of fifthing.

A. GASTOUE : Le manuscrit de musique du Trésor d'Apt.

La musique à. Avignon et dans le Comtat du XTVe au XVIIIe siècle.

T.GÖLLNER : Die mehrstimmigen liturgischen Lesungen.

M.d.C. GOMEZ : Quelques remarques sur le répertoire de l'Ars Nova provenant de l'ancien royaume d'Aragon.

U. GÜNTHER : La chapelle pontificale d'Avignon.

Unusual phenomena in the transmission of late 14 c. polyphonic music.

M. HUGLO : La messe de Tournai et la messe de Toulouse.

R. JACKSON : Musical interrelations between 14th c. mass movements.

P. JEFFERY : Notre-Dame polyphony in the library of pope Boniface VIII.

T.F. KELLY : Plainsong in the age of polyphony.

E. LE ROY LADURIE : Montaillou, village occitan.

LES COLLOQUES DE WEGIMONT: L'Ars Nova.

J. MAC KINNON : Representations of the mass in medieval and renaissance art.

D. PALADILHE : Les papes en Avignon.

N. PIRROTTA : Church polyphony a propos of a new fragment.

G. REANEY : Manuscripts of polyphonic music (1320-1400).

B. SCHIMMELPFENNIG: Aspekte des päpstlichen Zeremoniells in Avignon.

L. SCHRADE: Polyphonic music of the 14 c.

H. STÄBLEIN-HARDER : 14th c. mass music in France.

D. TANAY : The transition from the Ars Antigua to the Ars Nova : evolution or revolution ?

A. TOMASELLO : Music and ritual at papal Avignon (1309-1403).

Notes biographiques sur quelques musiciens du XIVe siècle

S. VAN DIJK : Medieval terminology and methods of psalm singing.

B. VINGTAIN : Avignon le Palais des Papes.

MASS IN THE PAPAL CHAPEL OF AVIGNON

(XIVTH CENTURY)

The

traveller arriving in Avignon from the west, by way of

Villeneuve-lès-Avignon and after crossing the Rhône, is struck, today as

he would probably have been in the Middle Ages, by one of the most

beautiful urban landscapes in France. The imposing mass of the Palace of

the Popes dominates the historic city nestling at the foot of the Doms

rock and encircled by the crenellated ramparts built by Pope Urban V.

The same traveller could not but ask himself the reasons for the

existence, in this average-sized town, of the most imposing Medieval

palace in the architectural heritage of France.

For rather less

than a century, the Christian world had its eyes turned towards Avignon

because the French popes lived there from 1309 onwards. Its wealth,

pomp, and corridors of power attracted kings, princes, and the greatest

artists of the century. From 5 - 6,000 inhabitants when Clement V

arrived, Avignon was to become the second largest town in France after

Paris within just a few years. There were thought to be 100,000

foreigners in the papal city in the middle of the century, and one can

imagine the frenzy of building that overtook the city, which never,

however, managed to build the required number of houses. Town houses,

churches, convents, cardinals in livery, and of course, the Palace of

the Popes, changed the face of Avignon and its immediate surroundings.

One can also understand the anathemas launched by Petrach, who denounced

the “attractions of Babylon”, against all the excesses of life in the

city.

It was the political situation alone which led Clement V

(Bertrand de Got) to settle in Avignon, temporarily, he thought, but

thereby perpetuating the tradition of the itinerant papacy of the 12th

and 13th centuries (several 13th century popes never went to Rome!).

“Ubi papa, ibi Roma” or “wherever the Pope is, there also is the seat of

Christianity”. Philippe le Bel, who had favoured the election of this

Gascon pope and who still had a strong influence on him, had encouraged

him to settle in a region where he could exercise his authority far more

easily than in Italy which was unstable and shaken by its many

political crises. For the entire century, the Church was the scene of a

power struggle between the different sovereigns of Europe which charted

the rise and fall of French influence. It was these same upheavals

within the Papal States which delayed until 1376 the return of the

Supreme Pontiff to Rome, where he was also Bishop.

French popes

were elected to the supreme office while the influence of the kings of

France within the college of cardinals remained strong, that is to say

throughout almost the entire 14th century. A series of contrasting

personalities succeeded each other to the Holy See. From the

authoritarian John XXII (Jacques Duèse born in Cahors) to the obstinate

Benedict XIII (Pedro de Luna from Aragon) who refused, right up until

his death in exile at the age of 95, to abdicate although the great

kings of the Christian world had long resolved to finally put an end to

the Great Schism. The austere Cistercian, Benedict XII for example (the

Gascon, Jacques Fournier), a great opponent of the Cathars1,

was succeeded by the brilliant, lavish, Clement VI (Pierre Roger from

the Limousin). Known as the “Magnificent”, he transformed the Curia and

the palace of his predecessor into one of the most spectacular courts of

Europe, making Avignon the capital of Arts and Letters. What these

different French popes had in common was on the one hand, very strong

diplomatic and political links, which often did not exclude a certain

degree of friendship, with the kings of France, and on the other, the

practice of “absolute nepotism” which saw each sovereign pontiff, with

the notable exception of Benedict XII, systematically appoint members of

his own family to the post cardinal or other important offices within

the Curia.

These colourful personalities spanned a century

particularly rich in radical developments, upheavals, and dramatic

events which were to end in the confusion of the Great Schism. The Black

Death of 1348 which entered the country via Marseilles is well-known.

In Avignon, it was, alas, only the first of a long series of plagues

(1348, 1361, 1397, 1406). France had 20 million inhabitants in 1328, as

at the end of the 17th century, but only 10 million in 1450! The effects

of incessant, devastating wars were added to the scourge of the plague.

At the end of the 14th century, the nobility, impoverished by these

ruinous wars, no longer really played its traditional role as protector

of the population and even seemed to be taking refuge in a sort of

relentless pursuit of luxury and pleasure. 14th century music naturally

reflects the world and troubled times of a society which was becoming

increasingly secular. The very foundations of medieval thought which

describe the world as the mirror of universal harmony were shaken by a

real scientific revolution which saw the beginning of reasoning without

recourse to religious faith. Naturally, it was during this century that

the artist's individual expression became strongly personal as he sought

to break free from traditional values.

Our programme is closely

linked to a prestigious, and relatively well preserved building, the

Palace of the Popes - built mainly by Benedict XII and Clement VI - and

in particular the Saint Peter Chapel (the “Clementine” chapel) in which

all the solemn liturgies took place. Many other places of worship

existed in the Palace which contained six chapels and very many rooms

large enough to install a portable altar. The reader must imagine

immense, empty spaces which can be visited today as they could in the

time of their splendour. The furniture was luxurious, on feast days the

walls were extensively covered with richly decorated hangings and

tapestries, a sumptuous pictorial décor glimpses of which can still be

seen today2. On certain grand occasions, crowds followed the

numerous processions and were allowed to attend the liturgy. People

pressed forward to see the cardinals' ornate robes, the glittering

decorations adorning the altar and the chancel, the magnificent papal

cathedra behind the altar, and to listen to the extraordinary new polyphonic compositions of the cantors, in their own stalls to the east of the Saint Peter Chapel.

In

the 1330s, unlike the period prior to this, the Church collected its

revenues very efficiently, and the coffers of the Treasury filled up

rapidly. It is difficult to imagine the rather unholy luxury of the

Avignon Curia. Although it may seem inappropriate to us today, it has to

be acknowledged that the Palace of the Popes quickly became an

established artistic centre, ideally placed half-way between Rome and

Paris, and one in which the greatest artists of the time - musicians,

painters, poets, sculptors, and architects - worked and lived. The

artists of northern Europe learnt the art of the fresco and the Italian

miniature there, whilst Italian artists became familiar with the

sculpture and architecture of northern Europe. At the beginning of the

reign of Clement VI, for example, five men who were among the most

brilliant figures of the century, the musician Philippe de Vitry, the

painter Matteo Giovannetti, the poet Petrach, the astronomer Johannes de

Muris, and the mathematician Lévi ben Gerson, doubtless had some very

rewarding discussions there together.

Within the Curia, “the

papal chapel” was an institution created by Benedict XII in 1334 to

replace the Roman “Schola Cantorum” which did not follow the pope on his

many travels. From the start, it included 12 chaplains, a number which

varied very little, and who should not be confused with the “table

companion” chaplains, high level dignitaries who took their meals with

the pope, and who were often advisors or high-ranking officers of the

Curia. This group of cantors was to acquire considerable renown during

the 15th century and its influence later attracted Dufay, Agricola, and

Josquin. Although the painters chosen to decorate the palace were mainly

Italian, the majority of clerics called upon to participate in chapel

life were from the north of France. Clement VI, in particular, continued

an already-established practice and institutionalised a tradition which

was to last more than two centuries, which explains the heavy French

influence on the papal liturgy, hitherto very Roman. These chaplains

were the best singers in the western world. The pope did not hesitate to

recruit them from the chapters of the great cathedrals or the private

chapels of cardinals and kings. Engaged to sing masses and the canonical

hours, they were also often composers of both sacred and secular music

and very probably had to participate in the entertainment at the end of

the meal by singing their motets for the pontiff and his distinguished

guests. In the name of the strict respect for the rule which forbade the

Curia any mixing of the sacred and secular, the pope could not have any

minstrels in his private service, but his chaplains and his guests'

musicians made up for this lack. The “merry pope who will listen happily

and quietly without displeasure”, described in a virelay in the

Chantilly manuscript was probably Clement VII (Robert de Genève), a

lover of extravagant festivities, who was known, what is more, to sing

admirably. His pontificate at the end of the century represented the

summum of Avignon pomp. The Vatican archives have fortunately been

preserved and give us a fascinating record of the exact name of all the

chaplains and their “magister” who succeeded each other at the Palace of

Popes. The accurately-kept accounts also tell us the high degree of

wealth that their office allowed them to attain at the end of the

century. The 14th century “cantors” gave the impression of a closed

caste, a unified brotherhood with a very high level of artistic and

intellectual achievement, and moreover, one which was acutely aware of

the fact. Contacts between chaplains of the various chapels were

frequent, and their repertoires seem to have circulated much more than

was at first thought.

This remark is particularly relevant to the

principal genre which concerns us here: the polyphonic mass. The

practice of singing the ordinary of the mass in polyphony developed

considerably in the second half of the century, on the initiative of the

papal chapel. The repertoire of the School of Notre Dame in the 13th

century already included several short texts (Kyrie, Sanctus, and Agnus)

set to a polyphonic melody, and 14th century composers took up this

practice, showing particular interest in the Gloria and the Credo since

their texts were longer and allowed for greater innovation. By the end

of the century, the polyphonic mass had become a very important genre

which was to spread rapidly from what was practically its sole centre of

creation, the papal chapel. The manuscripts on which these musical

masses have been handed down to us almost all come indirectly from the

chapel, even though many pieces copied and performed in Avignon were

perhaps composed elsewhere. The practice then was to choose, for a given

day, the different parts of the ordinary which were suitable for

singing, without there being any real musical relationship between them,

although the concern to create a unity which was not simply textual,

gradually saw the day. Masses from Tournai, Machaut, Toulouse, and

Barcelona are early exceptions however, and mass sung to a single cantus

firmus only appeared in the 15th century, with Guillaume Dufay.

Improvised polyphony had always coexisted alongside these new, highly

skilful compositions, and outside Avignon, the great cathedrals and

private chapels of the great princes, polyphony necessarily had to be

improvised. John XXII, in 1324-1325, protested against the abuses of the

young composers of the new school (Ars Nova), who introduced hockets

and short notes into their chants, and above all, as in the bulls of his

two predecessors, against the risks of secularising sacred song. The

situation changed radically in 1342, however, when Clement VI began to

systematically recruit the best singers in the north of France. From

this year on, the polyphonic ordinary was sung in the papal chapel but

it had probably been present on the principal feast days for a long

time. At the end of the century, polyphony was authorised at the masses

on all liturgical occasions except during the Passion, that is to say

for about 50 weeks, and even in the absence of the pope! On the other

hand, no polyphonic music existed for the canonical hours. The cantors

almost certainly had to improvise polyphonically on the plain-chant.

The

rule which was always respected in the papal chapel was the solo a

cappella chant, although the number of singers would have meant the

voices could be doubled, and this possibility was doubtless sometimes

exploited. The first mention of an organ concerns the chapel of the

antipope in exile, Benedict XIII, at the beginning of the 15th century.

Similarly, boys' voices, which were beginning to be used in the

cardinals' chapels were strictly forbidden in the service of the

sovereign pontiff. Three types of masses were celebrated in the palace:

the daily “missa secreta”, or “privata”, which was not open to the

public, was spoken and not sung, and which took place in a small private

chapel (in the past known as the “sancta sanctorum” in the Palace of

the Latran in Rome), the “missa coram papa” which was not defined by its

degree of solemnity but by the absence of the pope at the celebration

or by the fact that he attended but did not actively participate in it,

and the “missa magna”, the grand solemn and public mass, which was

always sung in the great chapel of Saint Peter in accordance with the

special ritual of the papal liturgy.

Strictly speaking, there was

no “school of Avignon”. The composers of polyphonic ordinaries simply

used and developed the three main styles in use at the time:

• the motet

style: as in the 13th century, a line, liturgical or otherwise, serves

as a support to one or two higher voices given texts which were often

different.

• the cantilena

style: under the “instrumental carpet” laid down by lower voices, a

single voice sings a text, in imitation of the rondos, virelays, and

secular ballads, but without a chorus.

Kyrie: the very

short liturgical text of the Kyrie is here amplified by a trope, an

ancient practice which came back into favour in the papal chapel. The

“De Fronciaco” heading in the manuscript concerns the town of Fronsac,

near Bordeaux, but we cannot tell if this was the composer's birthplace,

his name, or just the name of the piece. It is an extract from the

famous manuscript of Apt. Andrew Tomasello believes he has identified

the principal scribe and compiler of the manuscript: Richard de

Bozonville, the last choirmaster of the Palace of the Popes in Avignon,

and a native of St Dié. Appointed provost of the cathedral of Apt in

1400, he took with him the precious manuscript which included the

repertoire sung at the pontifical chapel.

Gloria: the two

upper voices intertwine and respond to each other as in many motets. The

author is Bosquet, that is to say Johannes de Bosco, a cleric from

Tournai and cantor in the papal chapel at the end of the century, who

worked under the direction of Richard de Bozonville.

Credo:

a piece from the Apt manuscript in conduit style, famous for its

dynamic rhythmic play throughout. The “Bombarde” heading may refer to

the author, probably Perrinet, a famous bombarde (wind instrument of the

shawm family) player, a minstrel in the service of the King of Aragon.

Sanctus:

a piece in a very homophonic conduit style, seemingly rather archaic in

this late Italian manuscript, and not without similarities to the first

complete cyclical mass in our musical history, the Tournai mass.

Moreover, the manuscript's heading mentions the neighbouring town of

Saint Omer, a very active urban centre in the 14th century.

Agnus:

also in the conduit style, this piece includes impressive ascending,

then descending, harmonic steps in each of the three parts of the Agnus,

which all have a similar beginning and a different ending.

Ite missa est:

a double isorhythmic motet from the Ivrée manuscript. Coming directly

from the papal chapel, this manuscript was probably written for, or in

honour of, Gaston Fébus, Count of Foix, Lord of Béarn, a great

connoisseur and lover of music. The two texts constitute what was known

in the Middle Ages as a “review of the estates”, that is to say

prescriptions and moral principles intended for all classes of society.

This was a genre frequently seen in Latin, but also in French. The use

made of it during the mass, was known in everyday language as “the

prayers of the sermon”.

The mass chosen is the mass for Christmas

Day, which was celebrated in the great Saint Peter Chapel whether the

Pope was present or not.

The introit, the communion, and the two short readings (collect and post-communion) are “sung in fifths”, improvised in a “chant on the written line” (cantus super librum).

This was a practice which consisted of embellishing the Gregorian

monody, which was flourishing and common until the 15th century, and

which is, however, completely neglected by today's performers. In

innumerable modest places of worship which had neither the prestige nor

the resources of the cathedrals and the princes' private chapels, it was

even the only form of polyphony practised during the whole of the

Middle Ages. The cantor Elias Salomon, in 1274, was already speaking of

the practice of improvisation on the written line in parallel, and not

contrary motion, and of the very “concertante” manner in which the

singers can apply it in practical terms under the direction of a

“magister” who also sings. Later, four treatises describe this simple

and natural ornamental procedure explicitly, and it is so obvious that

it is not, strictly speaking, even considered as polyphony, and based on

a very ancient oral tradition, perhaps specific to “langue d'oil” or

northern French countries. The unisons and crossing over of voices are

exceptions, contrary to the much more sophisticated descant. It is in no

way a “folk” practice, but a basic technique taught to young clerics,

and only intended for use in sacred music.

The procedure used for the gradual,

the addition of the faux-bourdon, is historically more subject to

caution, although all 20th century performers use it freely. Very

attractive to the ear, it is reminiscent of the organum of the School of

Notre Dame. The offertory is sung in simple monody.

It is

difficult for us singers to determine precisely what type of

interpretation was given to the Gregorian monody of the late Middle

Ages. Despite a certain continuity, the practice of plain chant varied

over the centuries. Rhythmically, the chant tended to level out perhaps

from the end of the 12th century onwards, under the influence of

Cistercian reform. But what tempo to choose? If the rhythm of measured

music slowed down significantly in the 13th and 14th centuries, Stephen

Van Dijk believes that plain chant, on the other hand, became a little

faster at the end of the Middle Ages under the influence of the

preacher-friars who wanted to devote more time to studies and sermons,

and less to the divine offices. And we know the important influence the

reforms of the preacher-friars had on the liturgical habits of the papal

Curia. The Roman liturgy, already very much simplified by Pope Innocent

III in the 13th century, was shortened still further in Avignon. The

text of the prayers is specified, and the chaplains eliminated the long

pauses in the delivery of the psalms. The papal chapel seems to have

significantly shortened all the offices, even those of feast days.

Although certain ceremonies were interminable (nine hours for the

crowning of Gregory XI!), this was due to the ritual and to the

particular ceremonial, notably the famous processions, but not to the

chants or prayers. On the other hand, we know that the plain chant was

always sung a little more slowly on the great feast days. Where the

Christmas Day Alleluia is concerned, we performed the Magnus Liber

version of the School of Notre-Dame. This may seem an anachronism in a

late 14th century mass, but listeners should take into consideration on

the one hand, that the organa from this repertoire were sung throughout

the century, in particular at Notre-Dame in Paris, of course, and on the

other, that the inventory of the books of the papal library carried out

in 1339 for Benedict XII in Avignon, describes two books, obviously

intended for singers, containing the repertoire of Notre-Dame. In

addition, the description of one of these two books reminds us very much

of the famous Florence manuscript, the most beautiful example of the

manuscripts from which this repertoire has been handed down to us and

from which the version of the alleluia we have chosen is taken. Finally,

François de Conzié, the last Grand Chambrier of the Palace of the Popes

at Avignon (the Pope's real “right arm”) explained in 1409 that the

organum might still be sung at the mass on special occasions!

Antoine GUERBER (Translation: Elizabeth Guilt)

(All rights reserved)

2

Recent research by B. Vingtain has shown that surprisingly, this was

not only due to the lavish Clement VI, but also to the supposedly

“austere” Benedict XII.