Le Livre Vermeil de Montserrat

La Camera delle Lacrime

medieval.org

lacameradellelacrime.com

Paraty 414125

2014

1. Le chant de la Sibylle [7:03]

2. O Virgo splendens [3:39]

LV 1

3. Polorum regina [5:13]

LV 7

4. Cuncti simus concanentes [5:47]

LV 6

5. Imperayritz de la ciutat joyosa ~ Verges ses par [3:44]

LV 9

6. Stella splendens in monte [6:53]

LV 2

7. Los set goyts recomptarem [7:03]

LV 5

8. Mariam Matrem Virginem [4:00]

LV 8

9. Rosa plasent [3:33]

melody: Bruno Bonhure

10. Laudemus Virginem

LV 3 —

Splendens ceptigera

LV 4 [2:27]

11. Ad mortem festinamus [5:56]

LV 10

12. Els Segadors [5:57]

LA CAMERA DELLE LACRIME

Bruno Bonhoure & Khaï-dong Luong

Sarah Lefeuvre — Voix et flûtes à bec

Tiphaine Gauthier — Flûtes à bec

Michèle Claude — Percussions, tympanon

Stefano Genovese — Psaltérion, tambour sur cadre

Andreas Linos — Vièle à archet

Jean-Lou Descamps — Vièle à archet et tanbura

avec la participation du

Jeune choeur de Dordogne

Christine et Philippe Gourmont, direction

Captation réalisée par France Musique dans le cadre du

concert à Sinfonia en Périgord, le 28 août 2013

Production : Paraty

Directeur du label / Producer : Bruno Procopio

France Musique

Direction artistique / Artistic Direction and Editing : Daniel Zalay

Ingénieur du son / Balance Engineer : Laurent Fracchia

Assistants / Assistant Balance Engineer : Christophe Goudin et Xavier Lévèque

Création graphique / Graphic design : Leo Caldi

Photographe / Photography : Khaï-dong Luong

Traduction de l’occitan vers le français : Didier Perre

Traduction du français vers l’anglais : Ivan Ilic

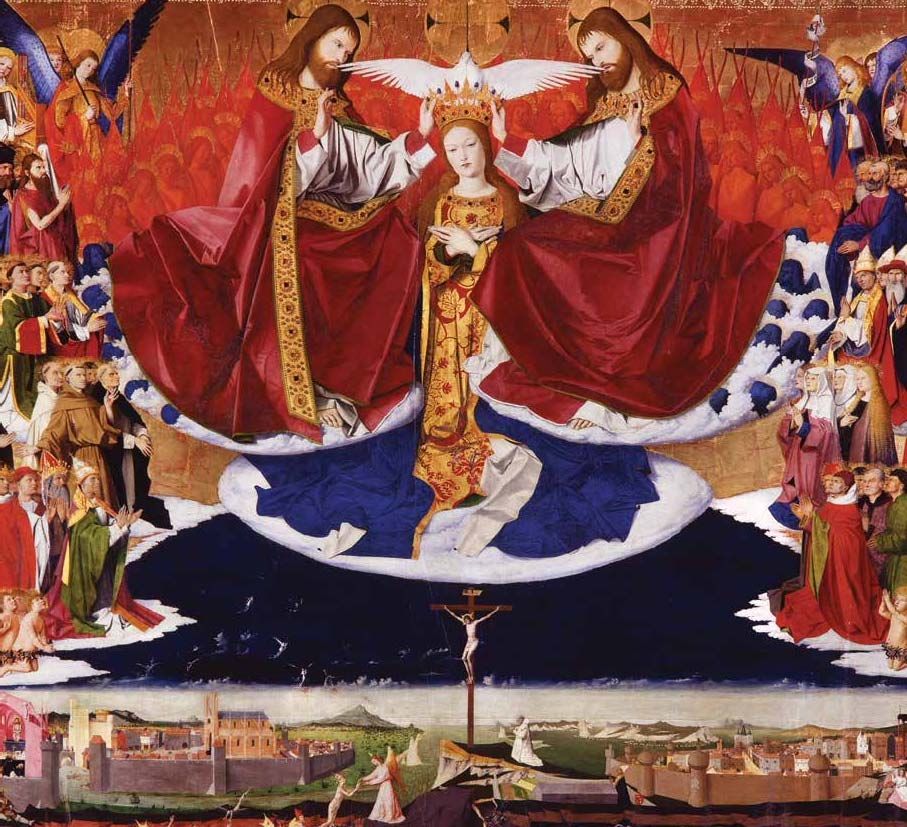

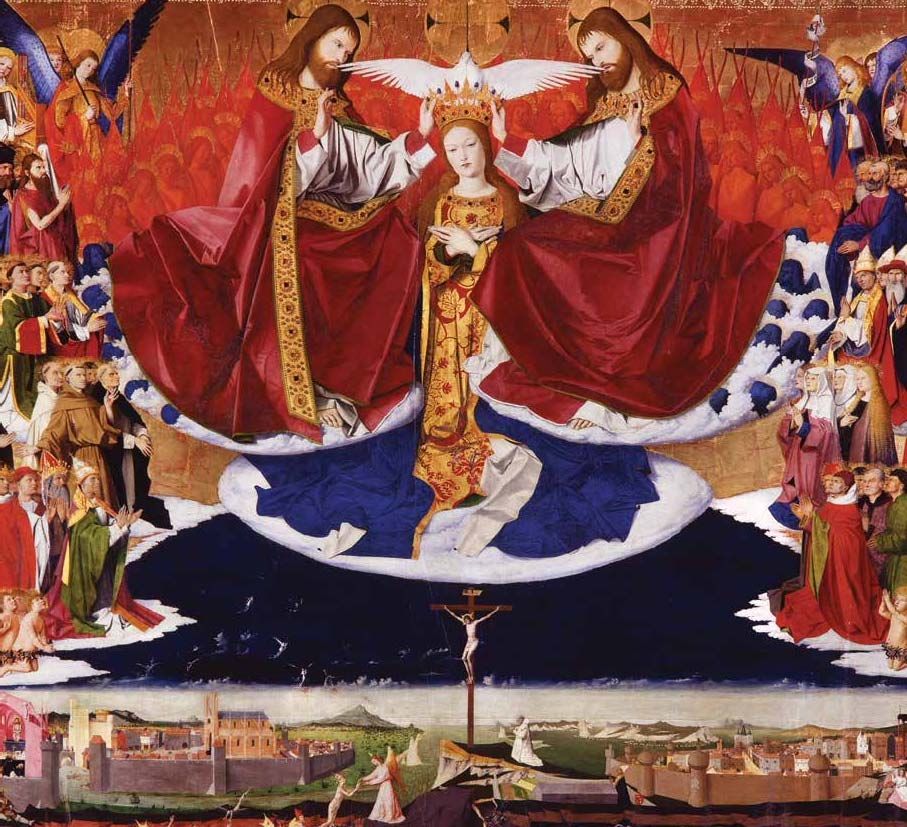

Couverture

/ Cover : Enguerrand Quarton, « Le Couronnement de la Vierge »

(détail), 1453-1454 ;

Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, Musée Pierre-de-Luxembourg

(Photo du musée)

Remerciements :

Un grand merci à toutes les

personnes qui ont participé à l’élaboration de ce disque, nous pensons

bien sûr au collectif du Périgord, Christine et Philippe Courmont, David

Théodoridès, les enfants du Jeune choeur de Dordogne, mais nous

voudrions également associer à notre souvenir les chanteurs des autres

territoires qui étaient à nos cotés

pour louer l’énergie du pèlerin

sur les chemins du massif de Montserrat : “Les croissants d’or” de

Lorraine, “Castella” de Picardie, “Volubilis” des Pays de la Loire, “Le

Choeur du Centre de Musique Sacrée” et “Arpège 122” d’Auvergne, “Les

Boucles d’Oise” d’Ile-de-France sans oublier les collégiens d’Auvergne,

d’Alsace, d’Ile-de-France, de Poitou-Charentes, de Picardie et de

Haute-Normandie… et merci d’avance à tous ceux qui nous rejoindront par

la suite.

Une pensée à la mémoire de Roger Tellart, critique musical,

qui veilla toujours à écouter d’une oreille attentive et à donner son

sentiment éclairé sur les trois premiers disques de La Camera delle

Lacrime.

Paraty2014

Imagine

the pilgrim’s exaltation! The toils and travails of the road are erased

by the joy of having reached one’s goal. The desire to sing, to dance,

in a word: to exult. There is one place in the Iberian Peninsula where

such conspicuous enthusiasm is the rule. Almost as well-known as

Santiago de Compostela, on which converge all those in Europe who wish

to commune at the grave of St. James the Great, the Monastery of

Montserrat in Catalonia draws innumerable devotees anxious to visit the

Black Virgin on which rests the establishment’s renown. Legend has it

that in 880, a miraculous vision led local shepherds to a grotto where

they found an image of the Saviour’s mother, which proved impossible to

move to a more accessible location. So the site was itself consecrated: a

chapel was built to house the image, and a monastery soon followed. As

Christian fervour fed on the Reconquista, forever pushing further back

the Iberian pale ruled by Islam, new levels of devotion accrued to the

Virgin of Montserrat. The polychromatic wooden statue that can currently

be admired in the sanctuary dates back to the early 13th century, when

communing with the Catalan miracle was no longer a peril, but an

adventure.

None of which alters the fact that on arriving at the

sanctuary, the ever-growing number of pilgrims created a delicate

practical problem. As convents are not hostelries with the calling of

welcoming visitors, always excepting passing noblemen, most pilgrims had

to remain in the Abbey-Church, men and women commingled, waiting for

the moment when they would be able to approach the altar and praise the

Virgin, begging her or thanking her for her protection. To successfully

balance the needs of monastery, parish and pilgrim was a daunting

proposition. Thus, in order to ensure that services, time for

contemplation, and festive celebrations not be mutually exclusive, the

monks of Montserrat devised a means whereby the energy of the faithful,

who fully intended to sing and dance on reaching the end of their

spiritual quest, could be reoriented to Marian devotion: using popular

themes, rhythms and melodies, enlivened with easily-memorised canons,

responses or refrains that could be taken up in chorus, or even

choreographed. It was an unusual formula, whose originality is marked by

the fact that at the time, having these distinct purposes cohabit was,

if not condemned, then at least previously unimagined This new concept,

which endured over the centuries, eventually gave birth to a repertoire

where the layman’s art grew in complexity as it interacted with the

learned, where the rules of plainsong meet those of ars nova, where roundels, virelays, goliards and courtly songs form a bouquet as sumptuous as it is unexpected.

It

is thanks to a precious manuscript, the fruit of a compilation

completed at the very end of the 14th century and preserved in the Abbey

of Montserrat’s library, that we know of the monks’ design. Only 137 of

the original 172 folios have survived. Among the numerous liturgical or

administrative documents, there is a short songbook (f.21v-27)

comprising ten anonymous songs. A note placed between the first two

songs specifies its mission: to assist those pilgrims who wish to occupy

themselves with singing and dancing during their vigil in the church of

the Blessed Mary of Montserrat, as much as outdoors during the daytime (“Quia

interdum peregrini quando vigilant in ecclesia Beate Marie de Monte

Serrato volunt cantare et trepudiare, et etiam in platea de die”), on condition that the songs remain decent and pious (“nisi honestas ac devotas cantilenas cantare”) and that care is taken not to disturb those who are deep in prayer or in devout contemplation (“ne perturbent perseverantes in orationibus et devotis contemplationibus”). Not that simple.

Fashioned

for the meeting place that was Montserrat, uniformity is scarcely the

rule here, no more in the music itself (four monodies versus six 2-, 3-

or 4-voice polyphonies) that in its notation (the style introduced by

Philippe de Vitry around 1315-1320 rubs shoulders with the square notes

of Gregorian parchments), nor in language, with liturgical Latin (eight

songs) competing with the local Catalonian, so closely related to

Occitan (two); nor in the choreographic options, with four songs being

accompanied by rounds (ball redon in Catalan), circle dances

where the dancers join hands. The whole assumes its own heterogeneity,

from its most ancient borrowings to its most modern biases, even when

the latter are wrapped in a “quaint” old style. A heterogeneity akin to

that of the pilgrims themselves, men and women from every land and every

background jumbled together in fraternal unity – the same unity that

gathers them, no longer smiling, in those Dances of Death that were

spreading over church walls as these songs were compiled, deriding human

vanity..

Across the centuries, the songs and dances that echoed

in the Abbey-Church of Montserrat retain all the flavour of their

uniqueness.

We cannot gauge the gap between these outbursts of

popular music and the plainsong tradition fostered by the monks of

Montserrat, as fires greatly depleted the treasures held in the library

of this holy place, to say nothing of the sacking of the monastery by

Napoleonic troops during the 1811 campaign. Luckily, the 1399 manuscript

was not currently there, having been loaned out for study to an erudite

Barcelonian. Who piously kept it. When, half a century later, his

descendants restored it to Montserrat, the monks clothed it in a cover

of wood and red velvet, earning it its contemporary name of Llibre Vermell de Montserrat.

By the latter part of the 19th century, the compendium had acquired so

great a renown that it was catalogued as the very first volume of the

new monastic library that its return symbolically re-established.

And

it is under this name, which might have been plucked from one of

Chrétien de Troyes’s romances, that this incredible document is now

known. A worthy salute to the legendary imaginings it illustrate.

Philippe-Jean Catinchi, Medieval historian

The Pilgrimage to the Moreneta: Joy and Exaltation

Nigra sum sed formosa…

The Llibre Vermell is a sort of practical manual for a well-conducted pilgrimage to the Moreneta:

it comprises religious poems, miracle tales, a calendar, a treatise on

confession, etc. It is famous because it includes the notation (words

and music) of nine pilgrimage songs. In truth, the manuscript contains

canticles that had no doubt already been popularised among the pilgrims

of Montserrat; the canticles are clearly by different authors in a

variety of styles.

One element of this diversity lies in the use

of language: two of the songs are in Occitan, one in Catalan – in the

Middle Ages the two languages were twins – and the others in Latin.

Their musical styles are likewise varied. Only two of the songs, Maria matrem and Impeyratriz de la ciutat joyosa are linked with the Ars Nova polyphonic style. The others are in a popular style, some of them including a refrain. One may note the Gregorian effect of O virgo splendens, Laudemus viginem and Splendens ceptigera.

The words of a tenth song, Rosa plasent, have been preserved thanks to a copy; Bruno Bonhoure has composed a melody for it.

All

authors have noted the stylistic heterogeneity of these songs, whose

only commonality is their aim of guiding pilgrims spiritually and

vocally, helping them avoid dishonest activities, as the text that

introduces Stella splendens in the codex demonstrates:

“When

they keep vigil in the church of the Holy Virgin of Montserrat,

pilgrims sometimes wish to sing and dance, likewise in daytime on the

church square. In this place, they must sing only honest and pious

songs; this is why some such are noted above and below. They must be

made honestly and with discretion, so as to not disturb those who pray

and are in contemplation.”

Thus the majority of the songs

whose melodies have been preserved are, if not popular, as least to

popular taste. Indeed, the guiding spirit of these medieval pilgrimages

was that of holiday, closer to popular fairs than to mystical

exaltation. Beyond the faith that was the pilgrims’ common culture:

these songs express the joy of being together and good cheer for the

road that has been travelled…

With the Dordogne Youth Choir,

Bruno Bonhoure and Khaï-dong Luong have preserved the responsorial

spirit of the songs with refrains, which is explicit in the manuscript

of Los set goyts, which specifies: ceteri respondeant (let all respond). Another responsorial hypothesis is proposed in Polorum regina between soloist, choir and instruments.

Stella splendens

is typical of songs in which an easily-remembered refrain replies to

narrative couplets intoned by the cantor. The latter joyously describe

the variegated crowd that comes to worship the Moreneta.

Only Ad mortem festinamus

does not invoke the Virgin, but rather reminds mortals of their

condition. The ensemble La Camera delle Lacrime proposes an

interpretation that evokes the ambience of the Dances of Death that

began to decorate sanctuary walls at the end of the 14th century.

It would be a betrayal of the Llibre Vermell’s

songs to mask the fact that they were, and have remained, a strong

element of Catalan identity. As though to emphasise this aspect the

recording opens with the Catalan version of the 13th-century Song of the Sibyl,

a song included in the Christmas liturgy. It describes the apocalyptic

prophecy of the Erythraean Sibyl, whose prophecy was set down by

Eusebius of Caesarea (around 265-339) and later transmitted by St.

Augustine.

Continuing in this vein of Catalan identity, the recording ends with the ancient version of the popular song Els segadors,

a lament recalling the Catalans’ revolt on 7th June 1640 against the

Castilian troops they were forced to feed and house. A modernised

version of this song, which was forbidden under Franco’s dictatorship

due to its use as a rallying song for the Republican partisans during

the civil war, became the national anthem of Catalonia in 1993.

Didier Perre

Councillor for the Langue d’oc

Le Puy-en-Velay, March 2014

La Camera delle Lacrime

Grouped

together around founding members Bruno Bonhoure and Khaï-dong Luong,

who created the ensemble in 2004, the musicians and artists of La Camera

delle Lacrime are committed to rediscovering and showcasing a

historical musical heritage while renewing it through their creative and

interpretative choices.

With the assistance of specialists and

scholars, La Camera delle Lacrime offers performances of music from the

past that dramatize the repertoire, making it more intelligible and

accessible.

The ensemble’s name pays homage to Dante Alighieri,

poet and friend to troubadours. Dante spoke of this ‘Chamber of Tears’

as a place where he would overcome distress and return to his roots,

re-emerging with newfound energy.

Bruno Bonhoure, musical director, solo voice, bombo legüero

Born

in 1971 in Aurillac, Bruno Bonhoure carries with him the heritage of

songs and tales that punctuated the peasants’ daily life in the Haute

Auvergne. Dedicating himself first to art history, his need for and love

of the stage led him to Paris.

Compared to the ‘Bildung’ (a

person who makes himself valuable by virtue of his own efforts) by Carlo

Ossola (Professor at the Collège de France) and to Giovanna Marini by

Lionel Esparza (Radio France), the quality of Bruno Bonhoure’s voice,

his stage presence and his personality make him one of the most

captivating French tenors on stage today.

As the ensemble’s

musical director, Bonhoure promotes the Occitan language through

multidisciplinary shows. His projects have offered a new interpretation

of the historical musical repertoire in Occitan and have been praised by

the Languedoc Academy of Arts, Letters and Sciences.

Khaï-dong Luong, staging, scenography, artistic co-producer

Born in Cambodia in 1971, Khaï-dong Luong arrived in France after fleeing the Khmer Rouge. With a degree from the Agrégation des mathématiques

and a Masters in Film Studies, his main focus is the creation of

alternatives to pre-established styles. Luong surprises and innovates by

restructuring habitual formats and brushing aside convention. He has a

contemporary vision of how to interpret historical repertoire which has

led him to consider new methods of communication; examples include the

participation of local singers in a show based around the Red Book of

Montserrat (the Llibre Vermell).

A multifaceted artist,

while in Chicago he co-wrote the documentary Someplace Else, which was

selected by the Los Angeles, New York and Chicago Film Festivals, as

well as a series of animated films selected by the Annecy Festival.

The Dordogne Youth Choir, Directed by Christine and Philippe Courmont

The Dordogne Regional Conservatory

The Périgueux Conservatory of Music and Dance

Created

in the year 2000 under the aegis of the Dordogne Regional Conservatory

and the Périgueux Conservatory of Music and Dance, the Dordogne Youth

Choir offers full vocal training to children and teenagers. With regular

concerts in Aquitaine, the Dordogne Youth Choir regroups some 35-40

youngsters in Grades 4-12 from Bergerac, Périgueux and Ribérac.

Christine

and Philippe Courmont have been particularly influenced by the

remarkable work of the Finnish Tapiola Children’s Choir and of the Radio

France Choral School, from whom they have retained essential

pedagogical principles that foster their work in Dordogne: constant

attention to the quality of vocal work, focus on the group’s musical

listening skills, promoting and respecting children’s voices, searching

for the young singers’ autonomy, a ‘collegial’ apprenticeship where the

teenagers participate in initiating the younger singers, the importance

given to staging and the singers’ bodily involvement. Encounters with

other conductors and other choirs, along with links to other disciplines

(dance, theatre…) further promote this artistic project’s quest for

open-mindedness.

The Dordogne Regional Conservatory is supported by the Ministry of Culture and the General Council of

Dordogne. The Périgueux Conservatory of Music and Dance is supported by the Commune of Périgueux.

The Sinfonia en Périgord Festival

was created in 1990. Dedicated to period instrument performance, the

festival is a joyful exploration of Early Music. The festival welcomes

the most innovative ensembles in late August of each year in the heart

of beautiful Périgueux.

The entire Sinfonia en Périgord team is

delighted to have supported the Livre Vermeil project alongside La

Camera delle Lacrime. The “Culture Loisir Animation Périgueux”

Association, which manages the Sinfonia en Périgord Festival, is a

longstanding partner of La Camera delle Lacrime, and strongly

contributed to making this musical adventure possible.

The Sinfonia en Périgord is supported by the Aquitaine Regional Directorate of Cultural Affairs (DRAC),

the Aquitaine Regional Council, the Dordogne General Council, and the cities of Perigueux, Chancelade and

Coulounieix-Chamiers. The festival is a member of the Federation of French Festivals.