medieval.org

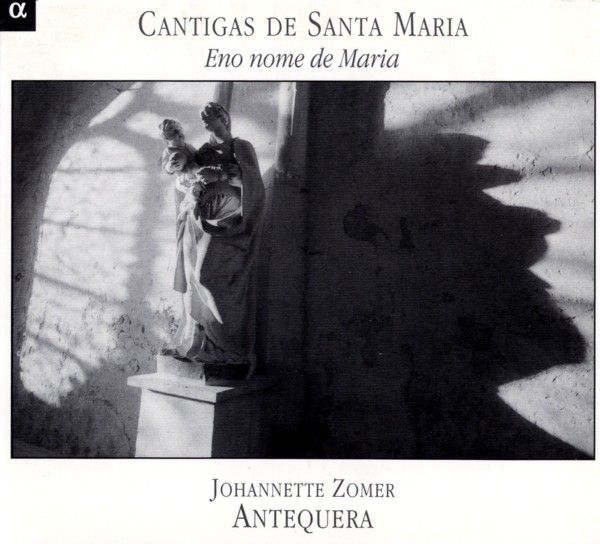

Les chants de la terre — Alpha 501

2003

medieval.org

Les chants de la terre — Alpha 501

2003

1. CSM 37. Miragres fremosos [6:25]

2. CSM 200. Santa Maria loei [5:13]

3. CSM 166. Como poden (instr.) [3:13]

4. CSM 329. Muito per e gran dereito [7:57]

5. CSM 412. Virgen Madre groriosa [6:17] [CSM 340]

6. CSM 1. Des oge mais [11:37]

7. CSM 260. Dized' ai trobadores [1:23]

8. CSM 15. Todolos santos (instr.) [3:32]

9. CSM 111. En todo tempo faz ben [4:24]

10. CSM 78. Non pode prender (instr.) [3:05]

11. CSM 70. Eno nome de Maria [6:47]

12. Prólogo. Por que trobar [7:34]

ANTEQUERA

Johannette ZOMER, chant

Sabine VAN DER HEYDEN, chant & synfonie

Carlos FERREIRA SANTOS, chant

Sarah WALDEN, vielle

Lucas VAN GENT, r'bab & flûte à bec

René GENIS, luth

Michèle CIAUDE, percussion

Robert SIWAK, percussion

Enregistré à Paris en décembre 2001 à Paris

Chapelle de l'hôpital Notre-Dame de Bon Secours

Enregistrement & montage numérique: Hugues Deschaux

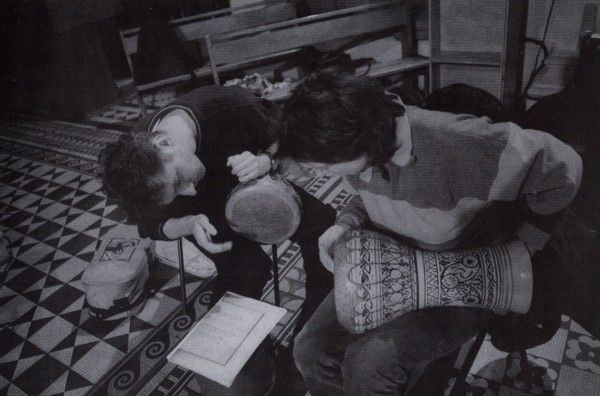

Photographies de Robin Davies

Antequera is a small town in the south of Spain 'whence the Moors came' as is mentioned in an old Spanish song. Ensemble Antequera has performed Cantigas de Santa Maria for over ten years. They have developed a performance practice based on improvisation. On the one band this is out of need, on the other it is out of choice. The cantigas have come down to us as single line melodies, without any information about how they were performed. Of course musicological research has provided us with a considerable amount of knowledge, but in fact there are no practical hints whatsoever. We know the perform ers of Alfonso's days had an enormous variety of instruments at their disposition. Many of these can be seen in the illuminations of the manuscripts of the cantigas themselves. Quite how people played, and what they played exactly, is not really known. We can be fairly sure, though, that improvisation played a large part in the performance of 13'" century instrumentalists. In this recording Ensemble Antequera have tried to replicate concert performance as nearly as possible; the improvisations are real and unedited. This may account for some imperfections which are an unavoidable part of improvising music. The spirit and essence of their peiformance has been captured masterfully.

Alfonso ‘El Sabio’. Trobador dos Trobadores

‘And what I want is to sing the praise of

the Virgin, Mother of our Lord,

Holy Mary, who is the best

thing He has created; which is why

my greatest wish is to be her troubadour,

and beg her to accept me as her

Troubadour and to receive my verse,

in which I desire to show

the miracles she worked...’

The text of the ‘Prólogo’ to the over 400 Cantigas de Santa María, leaves no doubt as to the humble intentions of the trobador: the poet uses his craft and art to praise the Holy Virgin, ‘e o que quero é dizer loor da Virgen’, and to sing about the miracles She performed: ‘mostrar dos miragres que ela fez’.

According to the ‘Prólogo’ the ideal trobador

has to meet certain requirements: apart from understanding

(‘entendimento’) he needs reason (‘razon’) to express what he thinks

and, so the cantiga adds meaningfully, what he ‘intends to say’.

Choosing

a lady to sing in praise of follows the tradition of the troubadours.

However, King Alfonso X (1221-1284), the possible poet of the Cantigas,

addresses his praise to the Holy Mary instead of a worldly lady. In

addition Alfonso adheres to another courtly tradition of medieval

Europe. He tells of his Lady's miracles in order to comfort and soothe

the suffering and to give courage, as contemporary sources on the art of

the troubadour frequently prescribe.

Not only subject matter and attitude, but also the very melodies and poems of the Cantigas

themselves are sometimes directly linked to the original tradition of

the French and Provençal troubadours. The shift of troubadour art from

southern France to the Spanish, Italian and Sicilian courts must be

blamed in large part on the Albigensian Crusade against heretics in

1209. The surviving troubadours had a huge influence on vernacular song

in the countries where they found refuge. The troubadour inheritance

lingered on in Spain even after it had long disappeared in France

itself.

Alfonso X ‘El Sabio’ was crowned King of Castile and León

in 1252 and became one of the most significant leaders in Spanish

history. Up until then Spain had had a history of virtually permanent

war; the Catholic north aimed at ‘liberating’ the Moslem south ever

since it had been conquered by Tarik ibn Sajid[sic, Táriq ibn Ziyád]

in 711. The population of Spain was always a mixed one in which there

was an amalgam of cultural styles and influences. In the north

Christianity dominated but people surely were familiar with the cultures

of the Arab and Berber invaders as well as that of the Jews. The

stories of the cantigas often mention these peoples; some are dedicated

entirely to the mishaps they have to endure until they invoke the Holy

Virgin, who, we learn from a cantiga in Alfonso's collection, ‘helps

even those of different faith when they turn to her’.

Known for

his learning, Alfonso fostered interaction between Christian, Jewish,

and Islamic intellectuals, as well as accepting the above-mentioned

refugees. Alfonso's work touched nearly every area of human activity,

from science to political reform; he even ordered a book to be compiled

about the game of chess. Alfonso's role in the production of the Cantigas de Santa María

is not entirely known. He conceived and supervised the compilation and

it appears that at least some texts are his. They are typical of

cantigas in using the Galician-Portuguese language, which was the

language of Iberian medieval poetry. ‘Cantiga’ simply means a Spanish

medieval lyric, something which survives in quantity, in numerous

genres, distinguished by the type of narrative.

However, most cantigas survive as text only, making the collection of the Cantigas de Santa María

nearly unique for its music. Moreover, it is one of the largest

collections of medieval monophonic vernacular music. Whether Alfonso

wrote any of the music is unknown, but many of the songs in the

collection are certainly contrafacta. Some melodies have been identified as those of troubadour or trouvère

songs. That probably explains the fact that there is hardly a trace of

identifiable Arab or Jewish influence in the structure of the music. So,

even though the illustrations in Alfonso's manuscripts depict musicians

of all the cultural groups of Spain, it seems clear that the troubadour

style of music remained ‘intact’ to a great degree. It is very tempting

to presume that the musicians in the pictures might actually have taken

part in the execution of the music. In which case we might see Moors

and Jews performing Christian music... Of course, all of this is

speculation but there does seem to be a case for supposing that while

the subject matter of the texts and performance practice may have been

influenced by the various cultural elements in Spain, the actual

melodies and genre were more or less freshly borrowed from France and

Provence and remained rather more ‘European’.

Alfonso dubs himself ‘trobador’ and he clearly is in more

than one respect. In such cantigas as the Prólogo, nr 260 Dized' ai trobadores

and in the ‘loores’, we see him in his guise of master, telling us

listeners how to bring praise. In general terms his mastery can be

recognised in his marrying of Arabic Jewish and Christian influences

with the essentially Franco-Provençal art of ‘trobar’.

Of course

he and his entourage had to learn this craft, and sometimes adapted or

even copied the examples from the troubadours in a very direct manner.

The contrafactual setting of originally Provençal texts to new melodies

(no.70, Eno nome de María) or of existing melodies to new texts (no.340/412, Virgen, Madre groriosa) shows Alfonso's circle as pupils, willing to learn the art of their predecessors. The poetic structure of no.70 Eno nome de María can be likened to that of Dou tres douz non a la Virge Marie

by Thibaut de Champagne. In his chanson, Thibaut uses the individual

letters of the name ‘Marie’ as topic for each verse. In the cantiga

(with the same subject) a similar principle is adhered to, this time

within the even more stringent structure of an acrostic.

The melody of no.340/412 Virgen, Madre groriosa was taken from Cadenet's S'anc fuy belha ni presada.

Apart from that, there is a distinct textual relationship as well.

Cadenet's chanson belongs to the ‘alba’ genre in which the dawn (alba or alva)

is the final focus of every verse. Dawn sheds light on an amorous

situation, in a literal as well as a metaphorical sense. The cantiga

(one of the loores) praises Mary as the bringer of light: ‘Thou art the dawn of dawns’.

Alfonso's

cantigas survive in a number of beautifully illuminated manuscripts,

the compilation of which he himself had ordered. Each cantiga has a

number; there are more than 400 in all. Every cantiga also has a line of

introductory text, which at times can be very elaborate, but usually

merely states what the cantiga is about. The collection is arranged

according to type. There are two types of cantiga: the loores and the miragres.

Every tenth cantiga is a loor,

a cantiga in honour of Holy Mary. Usually these cantigas have no

narrative but simply tell us to honour Mary and why we should do so.

Virtually everything will do as a good excuse to bring honour to her:

her beauty, her righteousness, her kindness, her fortitude in battle

etc. Down to the letters of her name, which, as we are told in cantiga

no.70 Eno nome de Maria, represent words that describe her

marvellous qualities. Her perfection is illustrated by the fact that all

that she is, is expressed by the letters of her name, ‘of which there

are five, and no more’. No.200 Santa Maria loei is a somewhat

more personal statement, maybe even from Alfonso himself as it reads: ‘I

honour, and I will honour’. On the whole the narrator of no.200 gives

testimony about the help and support he has always felt from the Virgin

Mary. Cantiga 260 Dized' ai trobadores presents us with a whole

string of reasons why we should thank Mary. One of these is the simple

fact that it is thanks to her that we know how to ‘trobar’, how to sing

these songs. The last of the loores on this recording, no.340/412 Virgen, Madre groriosa likens the Virgin Mary to the dawn which sheds light on the erroneous ways of sinners and helps them to repent.

The miragres

on the other hand are story-telling songs. They contain a great deal of

narrative about the miracles that Mary performed, and are meant to show

how worthy Mary is of our praise. Among the stories found there are

many fantastic texts about wars, disease, plagues etc. For example

cantiga no.37 Miragres fremosos is about a man whose foot hurts

so much that he is advised to chop it off. He keeps praying to Mary and

during his sleep she comes to massage his foot, which eventually results

in the pain disappearing.

There are also tales of people who

were in despair for some reason or other. In these Mary is always shown

to be willing to help those who are in need and turn to her. She can

even revive people who are in fact dead, as we can learn from cantiga

111 En todo tempo faz ben in which a wanton, lewd monk drowns in

the river Seine but, after four days, is revived by Mary because he had

started to pray and say a psalm. Her powers seem quite limitless. In

similar fashion cantiga 329 Muito per e gran dereito tells us

about a sinful Moor who, after stealing treasure from a church, is

turned to stone but is brought back to life when his comrades return the

loot and repent.

When all is said and done, Alfonso champions

his lady as the ‘alva dos alvores’ (the ‘dawn of dawns’), the ‘sennor

das sennores’ (‘lady of all ladies’), the ‘rosa das rosas’ (‘rose of all

roses’) and the ‘fror das frores’ (‘flower of all flowers’); who better

to call the ‘trobador dos trobadores’?

Anthony Fiumara & René Genis