medieval.org

Alpha 054

2004

medieval.org

Alpha 054

2004

I. L'AMOUR ET LA JEUNESSE

1. Amoroso [2:15]

Manuscrit de Marguerite d'Autriche

dessus de vièle, cornet muet, luth, percussions

2. Le grand désir [4:45]

Loyset COMPÈRE (1445-1518)

mezzo, ténor, cornet muet, ténor de vièle, luth, percussions

3. Saltarello [5:37]

Estampie italienne

dessus de vièle, guiterne, cornet muet, luth, percussions

4. Tenez ces fols en joye [3:28]

Manuscrit de Bayeux (1515)

mezzo, ténor, cornet muet, ténor de vièle, luth, percussions

5. [4:48]

La Danse de Cleves | Manuscrit de Marguerite d'Autriche

Hellas mon cueur | Manuscrit de Bayeux (1515)

ténor, cornet à bouquin, dessus de vièle, guiterne, luth, percussions

II. L'ARBRE DE MAI

6. Bon jour, bon mois [2:25]

Guillaume DUFAY (c.1400-1474)

ténor, cornet muet, ténor de vièle, luth

7. Resvelons nous, amoureux ~ Alons ent bien tos au may [2:00]

Guillaume DUFAY

mezzo, ténor, cornet à bouquin, ténor de vièle, percussions

8. Petits riens [1:46]

anonyme

guiterne, dessus de vièle, cornet à bouquin, luth, percussions

9. Ce jour de l'an voudray joye mener [3:28]

Guillaume DUFAY

mezzo, cornet muet, luth, ténor de vièle

10. Parlamento [5:42]

Estampie italienne

ténor de vièle, cornet muet, guiterne, luth, percussions

11. Vergene bella [3:34]

Guillaume DUFAY

mezzo, ténor de vièle, luth

III. LA GUERRE ET LE ROY

12. Vive le noble roy de France [2:18]

Loyset COMPÈRE

ténor, cornet à bouquin, ténor de vièle, percussions

13. Basse danse La Spagna [3:05]

Gulielmus L'HÉBREU (XVe siècle)

guiterne, cornet muet, ténor de vièle, luth, percussions

14. A cheval, tout homme à cheval [2:54]

anonyme

mezzo, ténor, cornet muet, ténor de vièle, percussions

15. Mit ganczem Willen [4:12]

1. Lochamer Liederbuch (c. 1450)

2. Conrad PAUMAN “Fundamentum organisandi” (1452)

3. Buxheimer Orgelbuch

mezzo, guiterne, ténor de vièle, cornet muet, luth, percussions

IV. AU SOIR DE LA VIE

16. Quel fronte signorille in paradiso [2:19]

Guillaume DUFAY

mezzo, ténor, ténor de vièle

17. Par droit je puis bien complaindre [3:18]

Guillaume DUFAY

mezzo, cornet muet, ténor de vièle, luth, percussions

18. In tua memoria [3:23]

Arnold de LANTINS (XVe siècle)

mezzo, cornet muet, ténor de vièle, luth, percussions

19. Pues no mejora mi suerte [2:46] Cancionero de la Colombina (XVe siècle)

ténor de vièle, cornet muet, luth, percussions

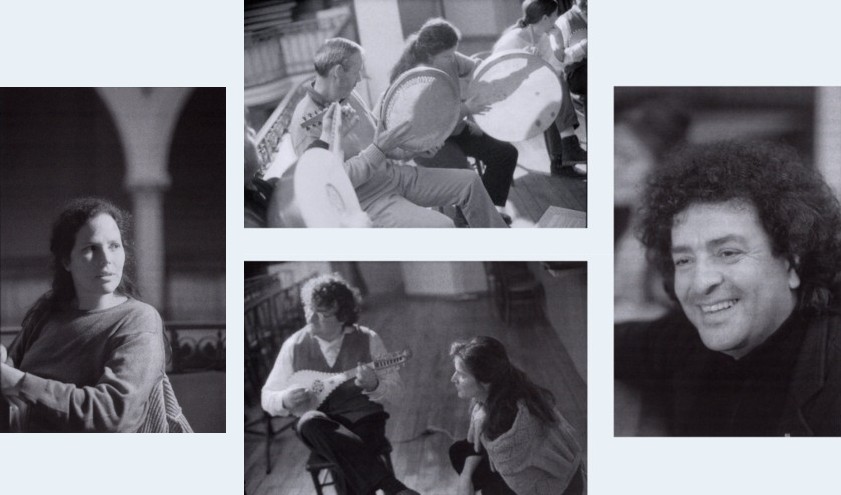

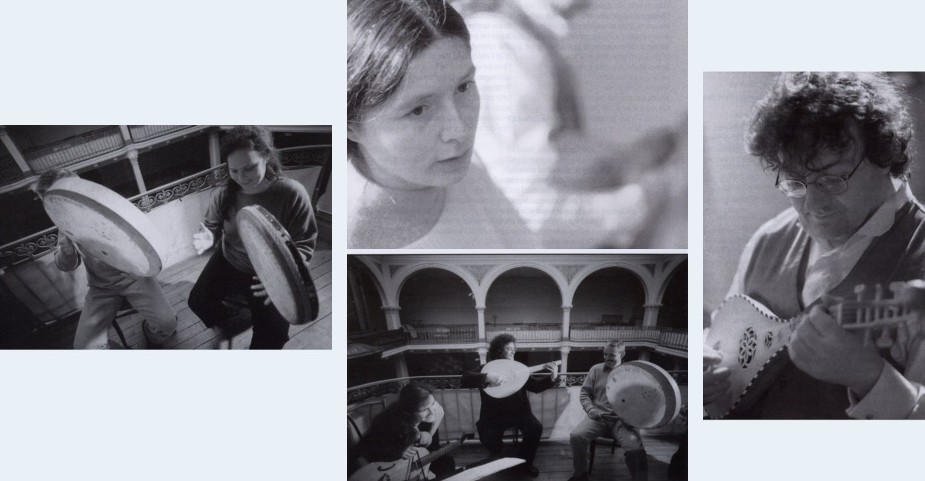

ENSEMBLE ALLÉGORIE

Caroline MAGALHÃES, mezzo-soprano

Emmanuelle GUIGUES, vièles

Marie GARNIER-MARZULLO, cornet à bouquin & cornet muet

Francisco OROZCO, ténor & luths

Jean-Paul BAZIN, guiterne

Bruno CAILLAT, percussions

Roger TELLART

Roger Tellart

Cornet muet - Serge Delmas, 1998

Cornet à bouquin - Serge Delmas, 1999

Vièle ténor - Bernard Prunier, 2002

Vièle soprano - Marcel Niederlender, 1985

Guiterne - Carlos González, 1991 (d'après Hans Ott, Nuremberg vers 1450)

Luth cinq chœurs en Ré - Ivo Magherini, 1991 (d'après Arnaud de Zwolle vers 1440)

Luth quatre chœurs en Sol - Carlos González, 1993 (d'après des modèles florentins de la fin du XIVe siècle)

Luth cinq chœurs en Sol - Carlos González, 1998 (d'après Gérard David)

allegorie@free.fr

Enregistré en juin 2002

Chapelle du Couvent de la congrégation Notre-Dame de la Providence de Portieux

(Vosges)

L'Ensemble Allégorie, sur instruments anciens,

bénéficie du soutien du Conseil Général des Vosges

Prise de son, direction artistique & montage : Aline Blondiau

Photographies du livret : Robin Davies

Transcriptions :

Catherine Baud-Fouquet, Maria Grazia Bevilacqua, Caroline Magalhäes & Bernard Houot

Production 2002 © 2004 Alpha

Ce disque propose un itinéraire précieux dans l'école musicale la plus

représentative du XV siècle : celle du duché de Bourgogne, sous le règne

de Philippe le Bon. En fait, non pas duché, mais vrai empire,

assurément l'une des puissances majeures de l'Europe du temps.

Les

Franco-Bourguignons, comme on les appelle alors, dominent au soir de ce

premier âge d'or et, parmi eux, se distinguent les profils de ces

musiciens cosmopolites à la carrière internationale (le pionnier, dans

ce registre, fut le maître de l'Ars Nova Guillaume de Machaut, secrétaire de Jean de Luxembourg, souverain de Bohême, et familier des rois et des princes).

Un siècle après Machaut, la figure marquante de la musique occidentale est sans conteste Guillaume Dufay

(vers 1400 - 1474). Né dans le Cambraisis (peut-être à Fay) ou Chimay,

il a beaucoup voyagé, après une période de formation à la cathédrale de

Cambrai. Et notamment en Italie, à Rimini (à la cour de Carlo

Malatesta), Rome (au service de la papauté), Florence (où il écrit le

motet Nuper rosarum flores pour l'inauguration du duomo) et

Ferrare. Mais il a été également appointé, de longues années durant, par

les maisons de Savoie et surtout de Bourgogne, précisément, sous le

règne de Philippe le Bon. Là, il se liera d'amitié avec son exact

contemporain Gilles Binchois, chapelain du duc, comme le montre une

miniature du Champion des dames de Martin le Franc, où les deux

compositeurs sont représentés en entretien amical (Dufay près d'un orgue

portatif et Binchois tenant une harpe). Pour autant, il termine sa vie à

Cambrai comme chanoine (comme beaucoup de musiciens du temps, il était

clerc) et cette dernière période est certainement la plus productive de

son existence.

Musicien complet comme l'était Machaut, Dufay a

joué un rôle de premier plan, tant dans le répertoire séculier qu'au

sanctuaire, et dans tous ces domaines, a su parfaitement assimiler les

influences étrangères : la “contenance angloise” du grand polyphoniste

Dunstable et le style profane des cours transalpines. Cette couleur

italienne, volontiers pétrarquisante (l'hymne à la Vierge Vergine bella),

est sensible dans plusieurs des pièces exhumées par Allégorie, tandis

que la manière française domine dans les chansons d'étrennes Bonjour, bon mois et Ce Jour de l'An et que dans la chanson de Mai Resvelons-nous amoureux,

Dufay s'avère fin stratège en écriture, employant pour les deux voix

inférieures (qui sont en canon rigoureux) un matériau qui semble

emprunté au motet O sancte Sebastiano.

Ce qui prouve que dans le même esprit que la Renaissance et le

Baroque (le cas célèbre de Monteverdi sacralisant son Lamento d'Arianna en Pianto della Madona), le Moyen Age finissant ignorait les clivages entre sentiments humains et divins.

À ses côtés, de bons compagnons sont convoqués, qui lui font comme une haie d'honneur. Ainsi Arnold de Lantins (première moitié du XVe

siècle), né à Liège et qui travailla en

Italie (deux de ses chansons sont datées de Venise, en mars

1428).

Précisément,

il semble avoir bien connu Guillaume Dufay dans la péninsule. Les deux

artistes collaborèrent aux musiques ayant accompagné le mariage,

toujours à Venise, de Cleofa Malatesta avec Théodore Paléologue, (le

fils de l'empereur byzantin déchu Emmanuel II), en 1421, et chantaient

l'un et l'autre dans la chapelle du pape Eugène IV, à Rome.

En tout cas, le style de Lantins témoigne d'une

indéniable sensibilité méditerranéenne dans

la chanson In tua memoria qui est ici proposée.

Autre gloire de la chanson franco-flamande, le Picard Loyset Compère

- mort en 1518 - appartient en réalité à la génération qui a “fait” la

première Renaissance (il était le contemporain de Josquin des Prés et

d'Agricola). Il ressentit, lui aussi, le “désir d'Italie” et fut au

service des Sforza à Milan, avant d'être chantre ordinaire du Roi de

France Charles VIII (1486).

Maître de la chanson conviviale et légère, il pressent dans Vive le Noble Roy l'esprit descriptif et rythmique des “Batailles” dont le XVIe siècle sera friand (La Guerre

de Clément Janequin), tout en restant fidèle aux

anciennes formes (il reconnaissait avoir eu Dufay pour premier

professeur).

Et puis en marge de ces noms connus, il y a le foisonnement des compilations anonymes, tel le Manuscrit de Bayeux,

sans doute copié vers 1515, pour le compte du connétable

Charles de Bourbon (qui trahit son roi François Ier

pour passer dans le camp de Charles-Quint), mais contenant des chansons

pour la plupart écrites dans la seconde moitié du XVe siècle.

Pour

la réalisation de ce répertoire monodique, deux courants s'affrontent :

la conception polyphonique, en référence à la forme d'écriture dominante

de l'époque, et la reconstitution pour une voix avec accompagnement

instrumental (annonciateur du style monodique qui s'imposera avec le

Baroque).

Autre compilation - germanique celle-là - à laquelle puise l'ensemble Allégorie : le recueil du Locheimer Liederbuch,

composé à Nuremberg entre 1452 et 1460 et qui, dans le domaine de la

musique vocale, offre une manière de prototype à un genre polyphonique

qui sera très prisé, Outre-Rhin, jusqu'au cœur du XVIe siècle : le Tenorlied

(ainsi dénommé parce que le thème y est au ténor). À mi-chemin entre le

populaire et le savant, cette compilation est révélatrice d'un climat

poétique et musical — fait de naturel, de sentiments simples et d'un

lyrisme intimiste — que n'offre aucun autre répertoire. Les différentes

classes sociales y sont représentées : bourgeois, maîtres de chant,

clercs, simples amateurs, qui se retrouvent dans le bonheur mélodique

d'une écriture venue, certes, de l'art domestique et raffiné des Meistersinger,

mais que l'esprit communautaire de la Réforme reprendra à son compte

pour en tirer — une fois la mélodie passée au soprano — la forme du

choral.

Enfin, le XVe siècle voit la naissance de

formes purement instrumentales comme les tablatures d'orgue. L'Allemagne

y apporte également sa contribution avec le Fundamentum organisandi (1452) de l'organiste aveugle Conrad Paumann de Nuremberg et le Buxheimer Orgelbuch, un peu plus tardif (entre 1460 et 1470).

Ce

dernier recueil offre plus de 250 pièces, transcriptions de pages

vocales liturgiques ou profanes, et de danses, dont plusieurs

compositions empruntées à Dufay et Binchois et proposées comme point de

départ pour des arrangements et ornementations ultérieurs. A ce propos,

on notera que l'orgue, en définitive, est le seul instrument qui

présente un choix de sources et de documents nous permettant de suivre

son histoire depuis environ 1430 jusqu'à aujourd'hui ; à ceci près que

pour le XV' siècle, lesdites sources ne sont qu'allemandes, les œuvres

italiennes, françaises, espagnoles et anglaises ne nous ayant pas été

conservées. Et il ne faudrait pas oublier, en prenant congé, les danses

réveillées par le présent programme. Danses qui relèvent, bien

évidemment, du domaine instrumental et proviennent d'abord des XIVe et XVe siècles transalpins (le Saltarello, l'Istampitta Parlamento ou encore les variations sur la basse-danse La Spagna,

dues à Gulielmus l'Hébreu : un maître à danser de la péninsule, au

Quattrocento, très en faveur auprès des cours nord-italiennes, tels les

Este). Mais aussi de collections princières privées comme le riche

chansonnier de Marguerite d'Autriche.

Le plus souvent, une seule

partie est écrite dans ce type de répertoire, étant entendu que cette

voix mélodique était très certainement accompagnée par des percussions

que l'on ne prenait pas la peine de noter. Quant aux danses de l'Ars Nova ou antérieures, certains documents d'époque parlent d'Estampies (ou Istampitte)

interprétées par un groupe de jongleurs ou un quatuor de ménestrels

(vièles à archet ou violes) : une piste qui permet de supposer que,

comme pour le répertoire vocal, une polyphonie instrumentale, certes peu

élaborée, existait déjà pour accompagner ces danses.

Á propos de la réalisation :

Dans

son travail de résurrection, l'ensemble Allégorie a été guidé par

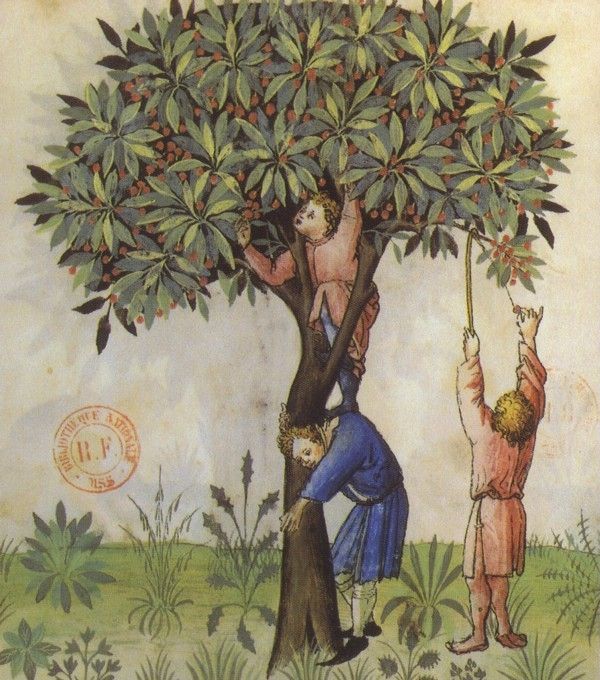

plusieurs idées. En premier lieu — et l'iconographie et la sculpture du

temps en témoignent — par le fait que, dans la musique profane, voix et

instruments avaient un rôle égal en importance. Le principe général

paraît avoir été, à ce sujet, de doubler chaque partie chantée par un

instrument colla parte. Mais les entorses a cette règle étaient

sans doute chose courante. De même, il était fréquent de transcrire pour

les seuls instruments une pièce composée a l'origine pour les voix ou

des voix accompagnées.

A partir de ces quasi-certitudes, Allégorie a imaginé

plusieurs hypothèses d'interprétation, conduit de plus

par l'idée que l'instrumentarium

changeait en fonction du lieu d'exécution (jeu en plein air ou en

intérieur) et que les musiciens d'alors, tous chanteurs au départ,

maîtrisaient chacun plusieurs types d'instruments (une polyvalence qui

vaudra aussi pour la Renaissance).

Saluons enfin la présence d'un cornetto muto

(qui renvoie au partage entre “hauts” et “bas” instruments) dans le

“concert” instrumental, où luth et guiterne, instruments éminemment

polyphoniques eux aussi, ont été choisis à la place de l'organetto. Cependant que le souci de couleur n'est précisément pas absent de Pues no mejora mi suerte, captivant emprunt au Cancionero de la Colombina (fin du XV siècle) qui conclut le disque.

This recording is devoted essentially to music by composers of the

Burgundian school, at the time when Burgundy, under the sumptuous rule

of Philip III the Good, was not so much a duchy as an empire, and one of

the major European powers1.

The Franco-Burgundians,

as they were then known, dominated the music of the late Middle Ages.

Among them, a number of cosmopolitan musicians distinguished themselves

through their international careers (the pioneer being the most

important figure of the French Ars Nova, Guillaume de Machaut, who was

secretary to John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia, and was regularly in

the service of the highest nobility).

A century after Machaut, Guillaume Dufay (c1400-1474)

was undoubtedly the leading composer of his day. He was born near

Cambrai (possibly at Fay or Chimay) and received his training at Cambrai

Cathedral. He then travelled widely, notably in Italy, where he worked

in Rimini at the court of Carlo Malatesta, Rome in the service of the

papacy, Florence, where he composed the motet Nuper rosa rum flores for the consecration of the duomo2

and Ferrara, composing for the d'Este family. But he also spent many

years in Savoy and (especially) at the Burgundy court of Philip the

Good, where he became friends with his exact contemporary Gilles

Binchois, who was a chaplain of the court chapel. A miniature

illustrating Martin le Franc's poem Le champion des dames shows

the two composers engaged in friendly conversation, Dufay with a

portative organ and Binchois with a harp. At the end of his life, Dufay

returned to Cambrai, where he was made a canon (like many musicians of

his time, he was a cleric). His later years were probably his most

productive.

Like Guillaume de Machaut, Dufay was a versatile

musician, excelling in both secular and sacred works and perfectly

assimilating the foreign influences that came his way: the ‘English

manner’ (contenance angloise) of the great polyphonist John

Dunstable and the profane style of the Italian courts. Italian colouring

shows in several of the pieces on this recording, including his setting

of the first strophe of Petrarch's Vergine bella, while the French manner predominates in his songs for the New Year, Bonjour, bon mois and Ce Jour de l'An. In the ‘chanson de Mai’ Resvelons-nous amoureux,

Dufay proves to be a cunning strategist, apparently borrowing the

material for the two lower voices (which are in strict canon) from his

own motet O sancte Sebastiano, and thus showing that musicians of

the end of the Middle Ages — like those of Renaissance and Baroque (a

famous example being that of Monteverdi, turning his Lamento d'Arianna into the sacred Pianto della Madonna) — made no distinction between human and divine feeling.

Arnold de Lantins,

who was born in Liège was another fine composer of the first half of

the fifteenth century. Like Dufay, he too crossed the Alps to seek his

fortune in Italy (two of his songs, written in Venice, are dated March

1428). The two men appear to have been well acquainted there. They

worked together on music for the wedding in Venice in 1421 of Cleofa

Malatesta to Theodore Palaeologus (son of the deposed Byzantine Emperor

Manuel II), and both were singers in the papal choir under Pope Eugene

IV.

Lantins' style shows an undeniably Mediterranean sensibility in the song In tua memoria, presented here.

Another great name associated with the Franco-Flemish chanson was Loyset Compère (c1445-1518),

who came from Picardy and was in fact an early Renaissance composer, a

contemporary of Josquin des Prés and Alexander Agricola. He too was

drawn to Italy: he was a singer in the Sforza family chapel in Milan,

before becoming chantre ordinaire to Charles VIII of France in 1486.

He excelled in the art of composing light, cheerful songs. His descriptive Vive le Noble Roy,

with its lively rhythm, looks forward to the battle pieces that were to

be so popular in the sixteenth century (Clément Janequin's chanson La guerre

is a fine example), while at the same time remaining faithful to

earlier forms (on his own admission, Dufay was his first teacher).

Apart from these well-known names, there was also a wealth of anonymous compilations, including the Bayeux Manuscript3,

which was copied around 1515 for the High Constable Charles de Bourbon

(who later turned traitor to his king, Francis I, and joined the service

of the Emperor, Charles V). Most of the songs in the manuscript

[represented on this recording by Tenez ces fols enjoye and Hellas mon cueur], were written in the latter half of the fifteenth century.

Only

one part is given for each of the songs, but they are generally

performed either as polyphony, with reference to the form of composition

that was predominant at that time, or as solo songs with instrumental

accompaniment, heralding the monody of Baroque.

Another collection of songs of the period, this time German, is the ‘Lochamer Liederbuch’, which was copied c1452-60 in Nuremberg and contains the earliest examples of the Tenorlied. The latter, which flourished from c1450 to c1550, was a specifically German type of polyphonic song, based on a pre-existing vocal line used as a cantus firmus (or Tenor).

Half

way between the folk and art genres, the poems and compositions are

natural in style and the climate created by their simplicity, intimacy

and lyricism is unlike that of any other collection. Various categories

of singers are mentioned in the book: members of the bourgeoisie,

singing teachers, clerics and simple amateurs shared in the melodic

delights of a style that stemmed from the refined, domestic art of the Meistersinger

and was later adopted by the communal spirit of the Reformation which

turned it into the chorale (with the melody firmly ensconced in the

treble line).

The fifteenth century also saw the birth of purely

instrumental forms, such as keyboard pieces in tablature. Germany again

made its contribution with the Fundamentum organisandi (1452) of the blind organist Conrad Paumann of Nuremberg4 and the slightly later Buxheimer Orgelbuch5

(some time between 1460 and 1470). The latter contains more than two

hundred and fifty pieces, transcriptions of liturgical or secular vocal

works and of dances, including several compositions borrowed from Dufay

and Binchois (who are not named) and proposed as a basis for subsequent

arrangements and ornamentations. It is interesting to note that the

organ is the only instrument whose history can be followed from c1430

to the present day, thanks to the many sources and documents that have

come down to us, but that, for the fifteenth century, those sources are

exclusively German, there being no extant Italian, French, Spanish or

English works from that time.

Mit ganczem Willen is presented here in versions from the Lochamer Liederbuch, the Fundamentum orgnisandi and the Buxheimer Orgelbuch.

Finally,

several dances are included in this programme. Fourteenth- and

fifteenth-century Italian dances belonging, of course, to the

instrumental repertoire: the Saltarello and Istampitte Parlamento, and variations on the bassa danza La Spagna by Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro,

a fifteenth-century Italian dancing-master, whose services were sought

by the most brilliant courts of northern Italy, including that of the

d'Este family of Ferrara. Other pieces — Amoroso, La danse de Cleves — are taken from one of the many private royal collections, the rich manuscripts generally known as the Chanson albums of Margaret of Austria6.

Generally

speaking, in this type of repertoire only the part performing the

melody was written down, but it was most certainly accompanied by

percussion instruments, which the author did not bother to indicate. As

for dances of the Ars Nova period or earlier, some contemporary

documents speak of estampies (or istampitte) performed by a group of jongleurs or a quartet of ménestrels (minstrels), playing fiddles (vielles)

or viols. This leads us to suppose that, as with the vocal repertoire,

instrumental polyphony, though not very elaborate, already existed for

the accompaniment of dances.

About this performance:

Allégorie's

performance of these works is based on factual information. Firstly,

that voices and instruments played an equally important part in secular

music (this is borne out by contemporary iconography and sculpture). The

general principle appears to have been to double each vocal part with a

musical instrument (colla parte). But it was no doubt common to

bend this rule, as it was also common to transcribe pieces originally

intended for voices or accompanied voices for instruments alone.

This

information being quite reliable, Allégorie went on to imagine several

possible interpretations, keeping in mind the idea that the instrumentarium

would change according to where the music was performed (indoors or

outdoors) and that musicians of the time, who were all singers at the

outset, each mastered several types of instruments (a polyvalence that

also applied to the Renaissance).

Finally, let us salute the presence of the cornetto muto

(referring back to the use of ‘hauts’ and ‘bas’ instruments) in the

instrumental ‘concert’, in which the lute and gittern, also eminently

polyphonic instruments, have been chosen to replace the organetto. There is certainly no lack of colour in the last piece on this recording, taken from the late fifteenth-century Cancionero de la Colombina8: the captivating Pues no mejora mi suerte.

Translation: Mary Pardoe

Translator's notes:

1.

At the time of Philip the Good (1419-1467) Burgundy comprised most of

eastern France and the Low Countries. His court became the centre of

European activity in music (as well as other arts). Instrumentalists

from France, Italy, England, Germany, Portugal, Sicily and the Low

Countries were employed.

2. Brunelleschi's dome of Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore) was consecrated in 1436.

3.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. 9346. The manuscript, containing

just over a hundred songs, is so called because in the early nineteenth

century it was the property of a librarian of Bayeux.

4. The Fundamentum organisandi is in the Staatsbibliothek, Berlin, with the ‘Lochamer Liederbuch’ (both Mus. 60413).

5. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cim. 352b. There is evidence to suggest that Conrad Paumann (c1410-1473) may have been the driving force behind the compilation of this manuscript.

6.

Margaret of Austria (1480-1530), the daughter of the Habsburg archduke

Maximilian (later Emperor Maximilian I) and his consort, Mary, duchess

of Burgundy, was regent of the Netherlands for her nephew Charles (later

Emperor Charles V) from 1507 until her death.

7. The ‘haut’

(loud) instruments, intended for use in the open air, included trumpets,

bagpipes, tambourines and shawms. The ‘bas’ (soft) instruments, for use

indoors, were the vielles, harps, flutes, recorders, crumhoms and

lutes.

8. Seville, Biblioteca colombina, 7-I-28.